We’re heading to the International Federation of the Red Cross (IFRC) Ebola treatment centre 15km out of Kenema town in eastern Sierra Leone. It’s known locally as the “Ebola camp” because it’s made up of a dozen or so white tented structures set up outside. It is surrounded by lush green forest and mountains loom in the distance.

Day shift staff arrive at 8am in a minibus, exchanging greetings, making jokes. Roughly 80 staff work here with an on-shift 2:1 staff-patient ratio. They include Ministry of Health nurses; government social workers; international nurses; members of the water and sanitation, body removal and burial teams; cooks; laundry staff; administrators and logisticians. Many staff are Red Cross volunteers from Sierra Leone as well as Norway and Spain, following national appeals.

In the month since it opened, the centre has admitted 52 patients, discharging 13 thus far and burying 22. The Red Cross wants to scale up from 30 beds to 60 in the coming weeks, but needs more staff to do so.

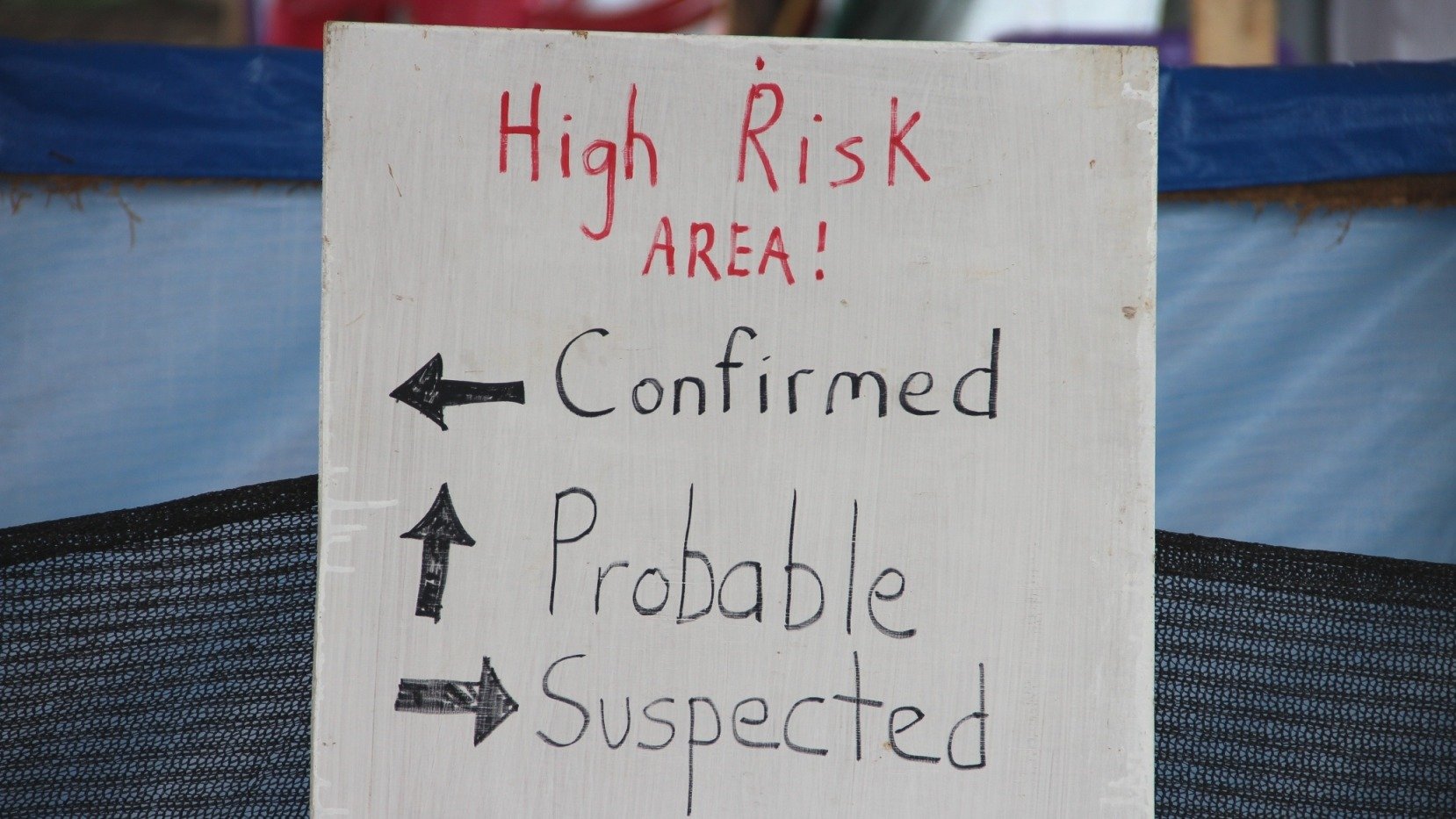

The day we are there the centre is holding 15 confirmed patients - one suspected, one probable, and one man dies over the course of the day. It is the first time IFRC is running an Ebola treatment centre. MSF trained them on every step of the process.

Leading the operation is a Spanish doctor, Marte Trayner Euxens, an emergency health specialist and long-time Red Cross volunteer, more used to doctoring following earthquakes or typhoons. “The biggest challenge here is that you’re responsible for your team’s security. You can never let your guard down, and you have to be very conscious of everything around you at all times,” she tells us. The other challenge for a doctor is that there is no clinical care to give: just palliative medicine - oral rehydration solution, painkillers, anti-malarials and antibiotics. They do not even give IV drips as they would pose an added danger to staff. “It is more of a nursing job,” she says. But she is happy to be here and her medical family supports her decision. “Patients have dignity and we humanitarians here need to help preserve it. I enjoy this work,” she says.

It is hard seeing so many patients die, says health worker Ibrahima Kemokai, but he is used to working with people in distress having nursed people through the latter part of the civil war in Sierra Leone.

“This is a very stressful disease to get, and you have to encourage people by telling them: you’re not the person with it, if you rest, you might get better. You have to change their mindset.”

Jestina Boyle, a government social worker working with patients, tells IRIN: “I try to tell people to relax, to take their medication, to remain calm, to follow the rules and eat and sleep well… I tell them: you may not die here - you may live.”

Merete Benestad, a volunteer nurse from Norway is on her first day in the job. “I decided to come and then I had second thoughts, especially because my colleagues were questioning my decision. I researched it a lot and in the end I said `yes’ without fear,” she said.

Despite all of the death and painful suffering around them, staff seem positive and grab every opportunity to celebrate or spread joy: joking with stronger patients, playing with the babies and children (while wearing PPE suits, which elicited a quizzical look in a one-year-old Ebola patient), singing and clapping to survivors as they exit the centre, distributing games and radios for recovering patients to while away the silent hours.

I chat to Edward Sannoh, 24, who earns US$100 a month to disinfect the dead and prepare their bodies for burial. He does not seem morose - the opposite: He is a natural joker with a wide smile and likes having an important job in a country where the bulk of youths are unemployed. “My family is not happy about it, but I’m still there. Someone has to do this job,” he says, beaming. Outside the treatment centre small crowds form - I initially thought they were curious locals, but a nurse informed me they were looking for work.

One of the hardest jobs is working on the water and sanitation team, say staff: the crew who must clear up the blood, vomit and faeces from patients who are haemorrhaging while in the severe stages of the illness. “This illness is extremely stressful for both patients and staff,” says Kemokai, “but we just try to get each other through it.”

Singing, prayer

Shortly after changing into hospital scrubs, staff commence their morning ritual: They stand facing those Ebola patients strong enough to sit outside their tent and recite a collective prayer. Then they break into song. One patient, Noah, 14, joins in, clapping, a bright smile on his face: he has received his second negative test and will be discharged later that day. A second boy, dressed in a bright yellow football shirt, remains silent, withdrawn: his mother died in this centre two days earlier, and he is here alone. There is little for him to smile about. I am not allowed to interview him as there is no guardian to contact to provide consent.

Thousands of children in Sierra Leone have been orphaned by Ebola and while some are staying with relatives and volunteer survivors are being trained to care for those whose families’ have rejected them, their long-term care prospects are still unclear, say children’s rights agencies.

The centre is designed so that patients in the high-risk area are separated from staff in the low-risk area by waist-high plastic fencing and a shallow ditch dividing the two areas by 1.5 metres. A group of five or six people in the confirmed ward spend most of the day together outside forming a make-shift family: a lone man, a 17-year-old girl who is caring for her Ebola-positive one-year-old sister as her mother just died on the ward, a woman (Hannah), and two teenage boys. They occasionally talk but mainly stare at the hustle and bustle of staff on the other side of the fence.

"How's the body?"

The open plan means staff and patients who are strong enough, can converse. I try to talk to patients but it feels a bit too public and forced and the physical set-up is vaguely zoo-like. Staff are friendly and full of smiles. One nurse asks patients how they are feeling. The lone gentleman who does not give his name gives muted responses. “How’s the body?” asks Jestina. “Fine,” says the gentleman, who is there alone. “The body is in the clothes?” - a common Krio greeting. “The body is in the clothes [I’m surviving],” he replies.

Ibrahim, a survivor at the Kenema hospital, says the staff kept him going mentally. “At first I had fear - people around me were dying. But the nurses came and talked to me and that fear finished,” he says.

There are three wards here separated - confirmed, suspected and probable cases. In the confirmed tent, an Ebola-positive woman is washing her clothes. Nurses hand out radios to patients. Several came with cell phones but there is nowhere to charge them. WFP in Guinea wants to provide Skype access so that patients can contact their families, but the logistics involved - who can touch the gadgets, how to maintain them - are complex in such a high-stress health security environment.

The IFRC centre has been up and running one month and thus far, no staff had contracted Ebola: so far so good. They do not have to report their temperature before entering the centre, which surprises me. Instead they have a buddy system whereby staff are paired up to monitor each other's welfare and safety. “We self-monitor here,” says Katherine Mueller, Africa communications head for the IFRC.

All over, staff are being trained - 17 new staff arrived that morning, including international nurses and volunteers - in how to put on and remove a personal protective suit (PPE); treatment protocols; which team does what and when; discharge protocols; how to disinfect and handle a dead body with dignity. Regular rounds of staff enter the ward in PPEs to deliver rehydration fluids and other basic medicines, to clean up patients’ beds and tents, to help bathe the weak, remove trash, bring in weak patients on stretchers and remove the dead.

It takes 20 minutes to put on a PPE and, as well-documented, they are searingly hot in the tropical sun. I witness a member of a cleaning team emerge from a tent staggering around like someone in a science-fiction film as he has overheated. A colleague guides him out and as he works through the slow process of PPE removal, reaching the most dangerous stage - goggle-removal stage. The sprayer shouts at him: “Take it slow. Do not rush. Remember to shut your eyes.”

“People just want to rip off the suit as quickly as possible because it is so hot,” says Mueller, “but it’s life or death.”

Staff can only enter wards in their PPEs for 20 minutes in the midday sun - up to 45 when it is cooler.

Only the goggles, heavy duty gloves, grey under-suit and boots of the PPE can be worn again once disinfected with bleach or chlorine - the rest must be thrown away, which in the case of this treatment centre, amounts to about 120 PPEs a day.

Lunch is served: Highly fortified WFP-provided corn-soya meal mixed with milk and sugar which staff hand over the fence to others in PPEs. The patients spoon it gingerly. How’s the meal? “Not so tasty today,” says Hannah. “I’m not so hungry.” Several survivors spoke to IRIN of a bitter taste that Ebola brings and of having to be forced to eat when they are at their weakest.

Survival and death

Most of the confirmed cases are too sick to leave their tents. Ebola symptoms can come and go in waves, so a patient who may gain strength enough to eat can take a sudden decline hours later. In the final stages patients “have a glazed-over look. They’re far away in another place,” says Mueller.

In the early afternoon the mood in the camp brightens: three people will be discharged today, Noah, 14, Idrissa, a 15-year-old boy and a woman in the probable ward who has been confirmed negative.

Mixing up probable cases in one ward is not ideal and can severely stress out patients, says an MSF staff member. The woman has been avoiding other individuals on the ward - too dangerous if they might be diagnosed positive. She looks sick and exhausted, but a hint of a smile creeps up on her face.

Noah, delivers smiles to the crowd awaiting him as he undergoes his “happy shower” - a chlorinated shower after which he is given a new set of clothing. His old ones are incinerated. But the boy will face considerable upheaval in the weeks to come: his mother died here, he has no father, and he does not yet know that his younger sister also died soon after arriving. He will be going to live with an uncle who lives in Freetown, far from his home town of Makeni.

Each survivor is given an Ebola-free certificate to help them talk down any doubters, as well as a sack of rice and other food from WFP, school fees for the children, and some clothing. As Noah walks past the laundry, staff shout to him “Freetown boy! Freetown boy! I want to marry you!” A Red Cross social worker hugs both boys - a shocking sight in a country where no one is touching. The staff are excited - they need these joys to keep going through the dark times - and form a quick paparazzi pool to photograph the discharges. Idrissa looks tired and overwhelmed - he moves to the shade to sit down on a stool away from the crowd.

Death and a new arrival

After they drive off, an ambulance arrives carrying a young girl from Freetown, whom the driver says is Ebola-positive. But according to my team-mate who was filming them, when the doctors at the treatment centre asked for her paperwork, the ambulance driver doesn’t have any. Some frantic phone calls ensue: the answer comes back - a confirmed case. Once through the gate the young girl steps down from the vehicle walking unsteadily - a group of healthcare workers in PPEs help her walk into the centre.

That night a policeman who was brought to the centre in an ambulance the evening before, too weak to walk and carried on a stretcher, dies.

The following day is Eid, a celebration day for Muslims, and the police chief is wearing a magnificent purple boubou when he arrives at the centre. “We have heard a rumour that our colleague is here. Is it true?” he asks the head nurse. “I am afraid your colleague passed away. We have informed his family,” she tells them. “But we too, are his family,” he says, sadly.

Later the man is buried in a small graveyard dug out of the bush next to the centre. There’s a light drizzle as a burly grave-digger shovels dirt onto his grave. A few family members come to pay their respects and his imam recites the last rites. Often family is too far away - or in some cases too scared - to attend. His grave will be marked by a simple stick - eventually he will get a plaque with his name on it.

Beside his grave are two freshly-dug plots ready for the next victims.

aj/oa/cb

This article was produced by IRIN News while it was part of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Please send queries on copyright or liability to the UN. For more information: https://shop.un.org/rights-permissions