When Bashar al-Assad was ousted from power one year ago, ending more than half a century of rule over Syria by his family, 38-year-old Amira* didn’t know how to feel. It had been eight years since she was released from one of the regime's Damascus prisons, and watching as others were freed from captivity brought up complex emotions.

Amira, who asked that her real name not be published out of concerns for her safety, spent a year in Adra Prison, where former prisoners and human rights groups say torture and abuse was rife. As the rebels who now head Syria’s transitional government defeated al-Assad, the mother of five told The New Humanitarian, “I still can’t describe how I felt. I was very happy.”

But as the doors of Adra and the notorious Sednayah Prison were opened, and other detainees spoke out about the horrors they had been through, Amira’s mental health began to decline. News reports and social media were flooded with videos of the terrifying conditions inside the prisons; photos and testimonials were everywhere on social media.

“Stories of women – about their torture and rape – were on the internet. People assumed the same thing had happened to me. They projected the stories they saw online onto me,” Amira explained. It made her uncomfortable to hear others make assumptions about what had happened to her.

While the period following the fall of the regime was extremely difficult for Amira, it also opened up a possibility she had never considered: She could get help. Since her 2016 release from Adra until late last year, Amira had never spoken to anyone about what happened to her in detention, where she says she suffered verbal and physical torture, but not rape.

A few weeks after al-Assad fled Syria, she contacted the Association of Missing Persons & Detainees in Sednayah Prison, an organisation founded in 2017 by a group of people who survived the prison, and their family members. They referred her to a newly established Damascus clinic run by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), where she has been receiving help since.

“My situation has changed a lot,” Amira said, speaking at the Damascus clinic in a low voice, sometimes smiling. “Since the regime fell, I have been going to meetings [with other survivors] and therapy [sessions]. I talk now, and when I talk I feel relaxed.”

A safe space

As she spoke, Amira occasionally glanced at her psychologist, Rand Nadar. Nadar, she said, made her feel that “this is a safe space”.

Nadar has been working for MSF since the NGO opened two clinics in Damascus for “survivors of ill-treatment in Syria”, having previously piloted the programme in Idlib, the province of northwest Syria that was long run by the rebels who took over most of the country last year.

“We have many cases like Amira’s; people who were released a long time ago and are now seeking treatment,” explained Nadar. “Before, they couldn’t talk about it. People felt threatened all the time,” she said.

The MSF clinics – which offer general medical consultations plus referrals to “specialised care, psychosocial support, and social work services” as well as links to local organisations who can offer other help – focus on people like Amira, who spent time in the dictatorship‘s vast network of detention centres.

It’s not clear how many people that includes. Thousands of people were released last December, but the Syrian Network for Human Rights reports that more than 177,000 people are still considered “forcibly disappeared” since the 2011 start of Syria’s war. Their fates are unknown. The watchdog group estimates that al-Assad’s government is responsible for 9 out of 10 of these disappearances, with other parties accounting for the rest.

This number, though, does not include those who are dealing with the mental health impacts of what happened to relatives or friends, those who were detained before the war’s official start, or released before its end. It also doesn’t take into account the sufferings endured by the rest of the Syrian population, who lived through conflict, sieges, hunger, forced displacement, and exile.

Research by the World Health Organization indicates that war has a serious impact on mental health, with 2019 data showing higher rates of depression and anxiety in conflict zones than the global average. The WHO and other health advocates say that early intervention can change the outlook for people dealing with issues like trauma. This has not been possible for most Syrians.

That’s not just because of the war, which decimated Syria’s economy and a health system that already had limited capacity to treat mental health problems. “In Syria, we have a huge problem with stigma around mental health issues,” said Nadar, who added that most of her patients come to the MSF clinic in secret, hiding it from their families, friends, and communities.

But Nadar has seen a small shift over the past year, and even over the course of the war. “As a result of the war, more people have started accepting the idea” of seeking out mental healthcare,” she said. “You can see it on social media… where people are starting to advise each other to go and see a mental health specialist if they need it.”

A long road ahead

While last December ended the al-Assad regime, in many ways Syria’s long war is not over.

In some cases, this is true on the ground: There have been violent attacks on groups seen as loyal to the al-Assads – especially members of the Alawite minority – prompting tens of thousands of people to flee across the border to Lebanon after a wave of killings in March. July saw the outbreak of violence against Druze in the country’s south.

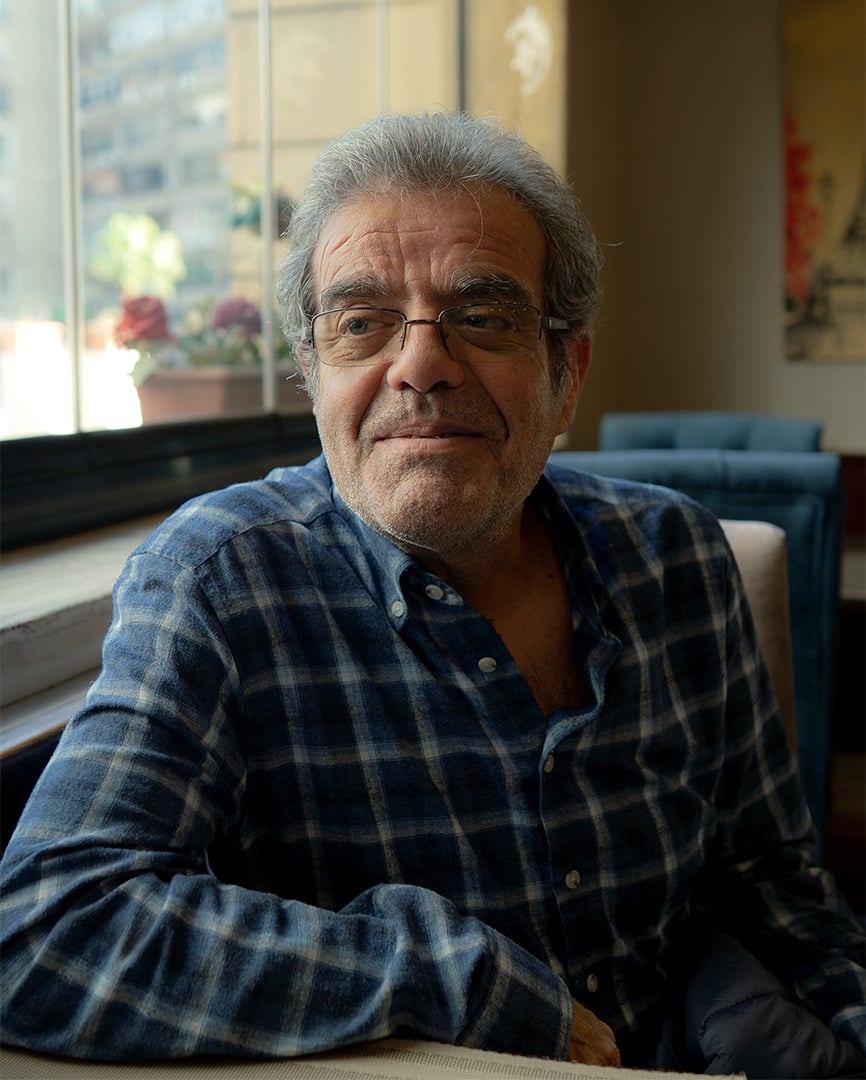

But in other instances, the ongoing fight involves confronting what happened during the war and dictatorship. “Psychologically and ideologically, in many places in Syria, the war is still going on,” said Dr Jalal Nofal, a psychiatrist who heads up the mental health team at the government’s National Commission for the Missing Persons (NCMP).

Nofal himself was arrested by the al-Assad regime four times before he fled the country for Germany in 2014. He later moved to Türkiye to work at a mental health centre for Syrian refugees, and returned to Syria in January this year.

The transitional government set up the NCMP in May, and appointed Nofal the following month. The body has been tasked with finding out what happened to Syria’s missing and supporting their families. One year on, relatives of the disappeared have expressed frustration at the slow pace at progress and what they see as a lack of engagement with the public.

Nofal and others from the commission say the process will take time, although he acknowledges that the slow pace is frustrating and says the NCMP doesn’t yet have the resources it needs for such a massive undertaking. For now, the role of his team is to meet with families of missing people across the country to identify their needs and build the foundations of how the commission will work.

“We are working with ambiguous loss; people who have lost their loved ones and don’t know where they are, if they are dead or alive,” Nofal said, adding that this kind of loss can be harder than knowing that someone is dead, with the uncertainty leading to more anxiety and distress.

Nofal believes the actual number of missing people is likely higher than current estimates. Plus, he said, “millions of people are affected” by the issue. “The nuclear families and extended families, of course. But what about neighbours and friends?”

Raising awareness

Rights advocates say survivors must play an important role in efforts towards truth, justice, and reconciliation – and that the current government needs to make sure it is not repeating the mistakes of the past, especially as it begins to try people accused of recent violence.

Ahmed Helmi, co-founder of Ta’afi (Recovery), a survivor-led organisation that supports victims of detention, torture, and enforced disappearance, said the group is now heavily focused on engaging victims in conversations about transitional justice. “We have been keeping these conversations and questions alive,” he said. “We cannot abandon or deprioritise this issue.”

Amira is part of that conversation now. She’s no longer ashamed of saying she was imprisoned or how it changed her life: Her husband’s family was pro-Assad, which caused complications. Amira eventually asked for a divorce. She now works as a teacher, supporting her five children without any support from her ex-husband.

It has been hard for other detainees, too. “Many are in difficult situations,” Amira said. “They need treatment, but they also need other services and financial support. And people don’t want to be a burden, they want to support their families.” They want jobs, she said.

Over the years, “many people have misunderstood me; they saw me as only a victim, and showed me fake sympathy,” Amira said. “Or they heard my story and acted like what happened to me is normal, not respecting what I went through.”

But these days, Amira says, “I’m a fighter. I consider myself a very strong person.” She now knows how she feels about the end of the regime; she’s glad al-Assad is gone. But she’s disappointed in the lack of help for other former detainees.

And she knows one thing for sure: “I choose when I want to talk.”

*Amira preferred to be quoted using a pseudonym.

Edited by Annie Slemrod.