I have always been conflicted and struggled with the idea of home.

I was born in Omdurman (the sister city of the Sudanese capital, Khartoum) in 2005, but my parents relocated to Qatar a year later and I was raised there with six siblings, five of whom were born abroad.

During my childhood, I faced racism, which was a very hard thing to understand. Getting into trouble with my peers at school who bullied me – just because I was not Qatari – and seeking assistance from teachers who would not believe me or even try to help, was a devastating experience to live with.

When I thought my parents would be my defense, I was met with a phrase I will never forget: “If you do not behave yourself, I will send you to Sudan.” I didn’t want to go to Sudan – at least not the way my father wanted me to go. That’s why Qatar was a very liminal place for me. It was where I lived a very blessed life, but at the same time I suffered from a deep disconnection.

In 2016, my father left his job in Qatar and decided to move back to Sudan. We had to enrol in new schools and adapt to a new environment altogether. But the bullying I had faced continued, this time because I was seen as the “Qatari kid.”

Classmates assumed I would be too soft to stand up for myself. But at least now, I didn’t have the looming threat of being sent to Sudan hanging over me. I felt free to defend myself – whether by speaking up or standing my ground. Here, there was no racial bias, because we were all the same. That gave me a bit of support.

Years passed, and as Sudan was changing, so was I. 2022 was the year I got into college, and that’s when I started moving around Khartoum more, getting to know the streets.

Photography became my way of expressing that journey. I can say that 2022 was the year I really became oriented with the city. I started calling it home – until 15 April 2023, when conflict broke out between the army and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

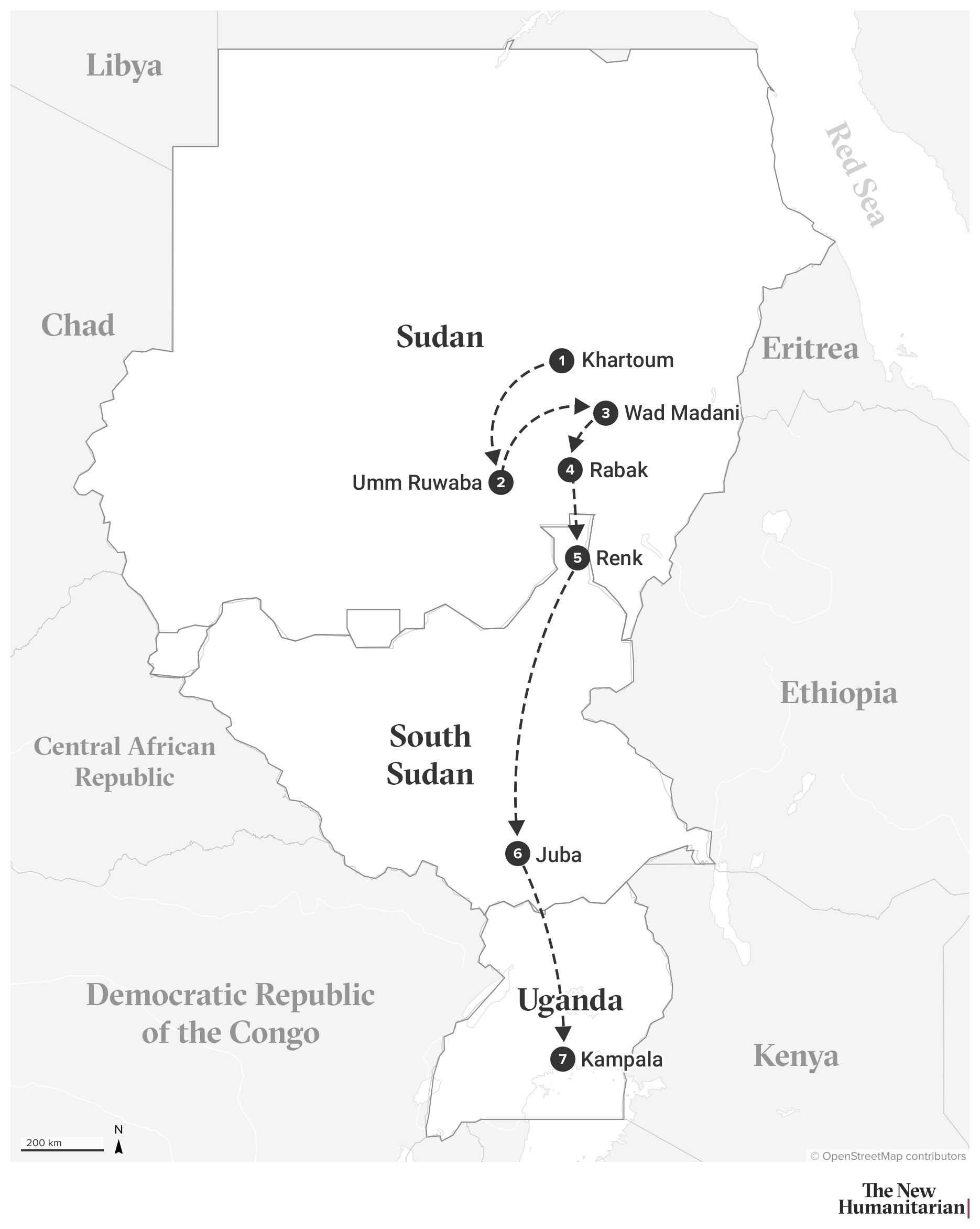

Soon after the war began, electricity was cut off, resources became scarce, and there was a constant fear of being caught in the middle of a gunfight. As a result, I began a journey to various places of refuge in Sudan – before eventually heading to South Sudan, and finally to Uganda.

The photos you are about to see depict this journey and explore the question that has followed me my whole life – of home, and whether I will ever truly find it.

Most photos are of different places I was displaced to, or of myself and family members. In some, I use double exposure to incorporate images from the past – including photos from my father’s digital archive – to revisit places I once called home, and to reflect on how my life was before the war.

After more than two years of working on this project, I realised that I may never truly find home – and that I no longer even have a clear definition for it. Still, I have not stopped searching for it: within my thoughts and emotions, in my displaced family and friends, and among my fellow refugees.

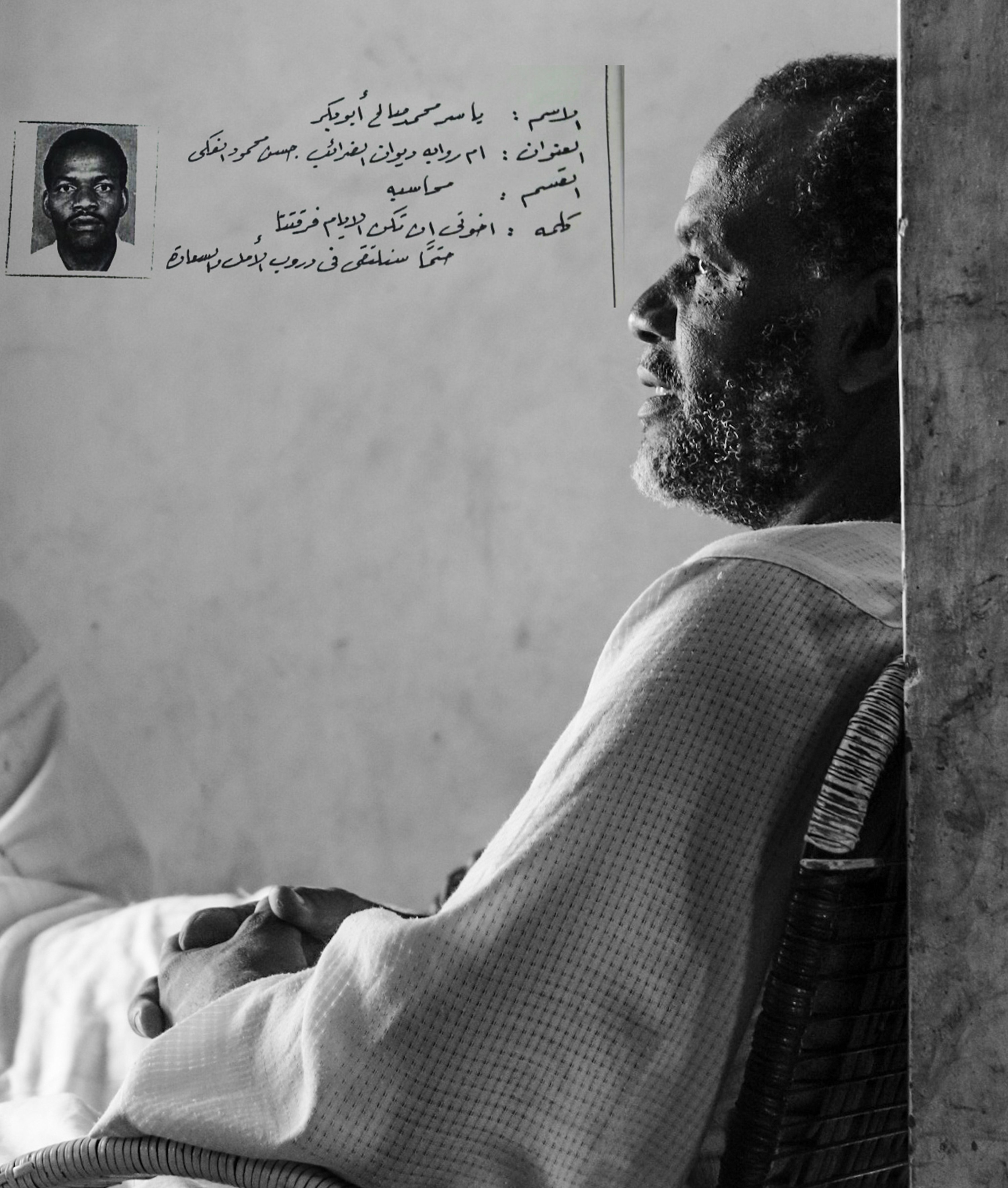

My father, my hero

This photo from 31 May 2023 is a portrait of my father, Yassir Mohammed Salih, taken while he was having a chat with my uncles and my grandfather, in our family house in Umm Ruwaba.

We escaped to Umm Ruwaba – in North Kordofan state – after a month of living under gunfire in Khartoum. Many members of my extended family gathered in the house.

The writing on the wall is a double exposure from dad’s graduation book featuring a quote he wrote: “Brothers and sisters, even if the days tear us apart, eventually we will meet at the roads of happiness and hope”.

The quote hit me hard because it was written in the late 1990s but is still relevant to our reality. It connected his generation and life with mine.

My father lost everything during this war but has remained optimistic – believing in Allah that one day everything is going to be better. He is a man who has a lot of faith, a man who I cannot describe enough. He is my hero, and I want to remember him like this.

The photo shows him in the house he was raised in, in the city he grew up in. Umm Ruwaba means home to my father – though it does not to me.

Same house, different time

This photo shows our front yard wall in Umm Ruwaba. On the right is my grandfather’s chair, his shoes, and a stool. On the wall, I double-exposed a second photo – an image my father took in 2014 of the Umm Ruwaba house salon, back when visitors were sitting, chatting, and drinking coffee.

Both photos show the same place, the same house – but from two very different times. They show how the energy of the house had changed, how movement and life in it had faded, even though it’s still the same people.

Families love each other – but in cramped places like this, tensions can build. Some people fought, there were dramas, and social pressures made it hard to relax. It certainly didn’t feel like home.

From market stall to military checkpoint

I took this photo of a house while on my way to the market in Umm Ruwaba. I asked people what had happened, but no one wanted to answer – probably because it was done by the RSF. They entered Umm Ruwaba in July 2023, turning our place of refuge into a place of fear.

The RSF portrayed themselves as heroes – offering protection after the police and army had abandoned the city – but they soon began robbing and killing, turning Umm Ruwaba from a strong, close-knit community into a very different place.

Market activity quickly disappeared, which deeply affected me, as I had been selling soap alongside my brother and cousins to earn income and support the family. As the eldest in the family, I was carrying the heaviest burden on my shoulders.

On 23 September 2023, I decided to leave Umm Ruwaba. I sold all of my photography gear to afford a ticket to Wad Madani – a city where large numbers of people had fled from Khartoum – hoping to find work or start over.

Getting out of Umm Ruwaba was a disturbing experience. Being asked by the RSF, “What is your tribe?” or ordered, “Hand over your phone,” then being searched by fighters – sometimes violently – was deeply traumatising.

Women were also searched and harassed, and I felt weak and powerless. Sometimes I regret not speaking up. But then I remember: There was nothing I could do.

Hope on a bumper

This is a screenshot of a video I took in November 2023, a couple of months after being in Wad Madani. The text on the tuk-tuk bumper says “Definitely we will go back”. It is a slogan that many Sudanese were using to project their hope of returning to their homes.

When I came to edit the image – which I shot while sheltering inside a tuk-tuk by the side of the road, where I had been selling mobile phone credit – I realised how different its message was with how I was feeling.

During the first months of the conflict, I was like, “yeah we will go home, it will be a two-week thing.” We didn’t take many clothes or possessions when we left Khartoum, and I felt that this thing would be finished shortly. But by late 2023 I was treating Khartoum as the past, and thinking I would never go back.

The sign displays a positive message, yet it’s written on a tuk-tuk that’s just passing by, and not returning anywhere. That moment symbolised something much deeper for me – the opposite of what the message intended: I’m not going back any time soon.

A new Khartoum

This photo was taken a month after I arrived in Wad Madani. I had the chance to reunite with friends I hadn’t seen in months. We had all fled from different states, and that night we were catching up, playing cards under the light of a lamp strapped to the back of a truck.

It was a very sentimental and emotional moment for me – one that reflected a growing attachment I felt towards Madani. Hundreds of thousands of people had arrived in the city from Khartoum state, and it was a very welcoming place. I started meeting people who are similar to me, people who shared my interests, who were seeking knowledge and careers they could feel proud and comfortable in. I began to see another Khartoum forming there.

At the same time, I didn’t truly feel at home. I was staying with a relative – a distant cousin of my father – and, while he was very welcoming, there were things he said that made me uncomfortable. He asked if I had considered working in Rabak, which is about three hours to the south, or in El Obeid, around eight hours west. He wasn’t kicking me out, but the way he suggested relocating made it clear I wasn’t expected to stay for long. So, while Madani felt almost like home, the place I lived in – and who I lived with – took that sense of belonging away.

In December, I then got a call from my father inviting me to come to Rabak so we could travel together and apply for asylum in nearby Renk, South Sudan. He had many reasons for wanting to leave Sudan – one of the biggest was that my siblings were no longer able to attend school. At first, I refused, and we argued. But on the morning I was supposed to head to Rabak, I changed my mind and decided to do what he wanted. It turned out to be a good decision: just days after I left, RSF fighters invaded Wad Madani and left disaster in their wake.

Journey to the unknown

I titled this self-portrait “A Family Journey to the Unknown”. It was taken in Rabak, as my family boarded a vehicle heading to Renk.

Rabak feels very sparse. It’s a rough environment in terms of daily life, and I never really connected with the community. The environment itself feels like it’s going through an identity crisis. Is it a city, or just a large village? It’s a strange place – I can’t even describe it clearly. And maybe that’s exactly why I don’t like it.

I’m not someone who enjoys posing for regular group photos, so I decided to take this candid image – one that could include me with them, without needing to pose. My mum, on the left, was having an argument with my younger brother, who was standing. Everyone was tense, stressed, and uncertain about what’s coming – but there was still a sense of hope. I’m on the outside, watching.

Renk, a border town in the north of South Sudan, is more of a transitory space, a first stop in the country for refugees and South Sudanese returnees, so I never expected to stay there for long. Throughout the journey, I was thinking, “what should I do next with my life? Should I head to Juba, the capital? Should I return to Sudan? Would Egypt be a better option?”

Thinking of everything at once

On the day after we arrived in Renk, we had to sit and wait to register as refugees, which is what is happening in this photo.

The man in the background of the image… I don’t know who he is but you can tell from his expression that he’s thinking about everything at once.

In the foreground, my brother Mujtaba who is two years younger than me was exhausted – you can see it in his eyes. We were tired of standing under the sun. The shade of a tent felt like salvation. Mujtaba should have been applying for university at this moment, but here we were instead. Not long after, he would start selling plastic bags just to earn something. A few days ago he finally finished high school exams – exams he should have finished two years ago.

Most of the photos I took in Renk were with my phone, often using my headphones and pretending to be on a call. I was a refugee, not a reporter. If anyone saw me holding a notebook or asking questions, they would report it to security.

Home-ish

I lived in this small tent with my family for three days in Renk as we completed the asylum application process. Strangely, I felt closer to home here than at any point since the war began. Unlike in Umm Ruwaba, here it was just my immediate loved ones. The constant talking and the small fights reminded me of home. That’s why I chose to double-expose this photo with an image – taken from my father’s archive – of our old family home in Omdurman, where we lived after leaving Qatar. Still, deep down, I knew it wasn’t home, and not where I wanted to be.

In the end, the authorities told us we would have to move from Renk to a remote rural refugee camp in South Sudan, so my family made the decision to return to Rabak. They didn’t want to live in a faraway place.

I decided to continue on to Juba. By that time, the RSF had already entered Madani. I had lost what little belongings I had left, and there was nothing to return to. I needed a new beginning, and I hoped Juba would offer a new opportunity – maybe a different kind of job, a different kind of life.

Conflicted

Taken in Juba, I titled this photo “Conflicted” to reflect the many emotions I was feeling. I wanted to go back to Sudan because I didn’t like Juba, yet at the same time I knew that here I had so-called safety and the space to grow.

I rented a room in Juba with a cousin of my father’s for $10 a month. I started working for a production company as a videographer and photographer, but it was my worst ever work experience. The company paid per project, not with a regular salary. There were weeks without any work, and sometimes months would go by with nothing at all. It was really tough.

I don’t remember much that I liked about Juba – mostly, it was the people I was with who kept me connected to the city, either from work, or my regular friends. Juba was tough. I’d walk to work and come back late. Most of the time, I was doing almost nothing except editing this project.

A mirror named Mohey

This is a photo of my friend Mohey, who I stayed with while I was in Juba. We first met in Umm Ruwaba, and his story reflects the struggles so many people have faced during this war and displacement.

Before the conflict, Mohey was a medical student at the University of Khartoum. He came to Juba hoping to apply to a university in Turkey, but his visa application was rejected. He then invested a huge amount of money into opening a pharmacy in South Sudan – but couldn’t get the licence he needed to operate. Eventually, he gave up and used the last money he had to pay for university in Russia. But on the day he was supposed to travel, he found his passport had been stolen.

At that point, he decided to head north. He travelled by car through South Sudan’s Upper Nile state, then continued overland across Chad, Niger, and Morocco. Eventually, he made it to Europe. He is now in France as a refugee – still trying to find a place to settle and call home.

In Mohey I found a reflection of myself. We met in Umm Ruwaba but neither of us felt connected to the place, then we went to Juba but weren’t connected there either. “I don’t even know what brought me to this place, and I wish I never came, and I know if I was at home right now I wouldn’t be in this situation,” Mohey told me in late 2024.

Upside down world

This double exposure shows the last landscape photo I took in Khartoum (at the bottom) with an image of Juba, taken in August 2024, upside down at the top.

By this point, I had been in Juba for seven months, but I still felt like a stranger – even the streets didn’t know me. I was losing touch with my photography practice because of the restrictions placed on street photography, and I missed my family deeply.

I wanted new opportunities, a space to explore my ideas and passion – some way to break free from what felt like a huge cage. I felt like a prisoner holding the key to my cell, but not knowing how to use it.

In this photo, I tried to show how Juba felt like a completely different world to me – so far from Khartoum and Omdurman.

Blurred memories

I left Juba for Kampala, the capital of Uganda, on 13 September 2024. It felt strange – I’d spent eight months in Juba, the longest I had stayed in one place since leaving Khartoum. Juba never felt like home, but to say that my time there meant nothing would be a lie. It mattered – but I knew I needed to leave.

I took this photo from the bus as we were leaving the city. It shows the Nile, and it was raining. I don’t remember much about my time in the city, and the raindrops on the window felt symbolic, like they were covering my memory, blurring the details.

This photo became a way of admitting that Juba was already starting to fade in my mind, even though part of me felt something as I left.

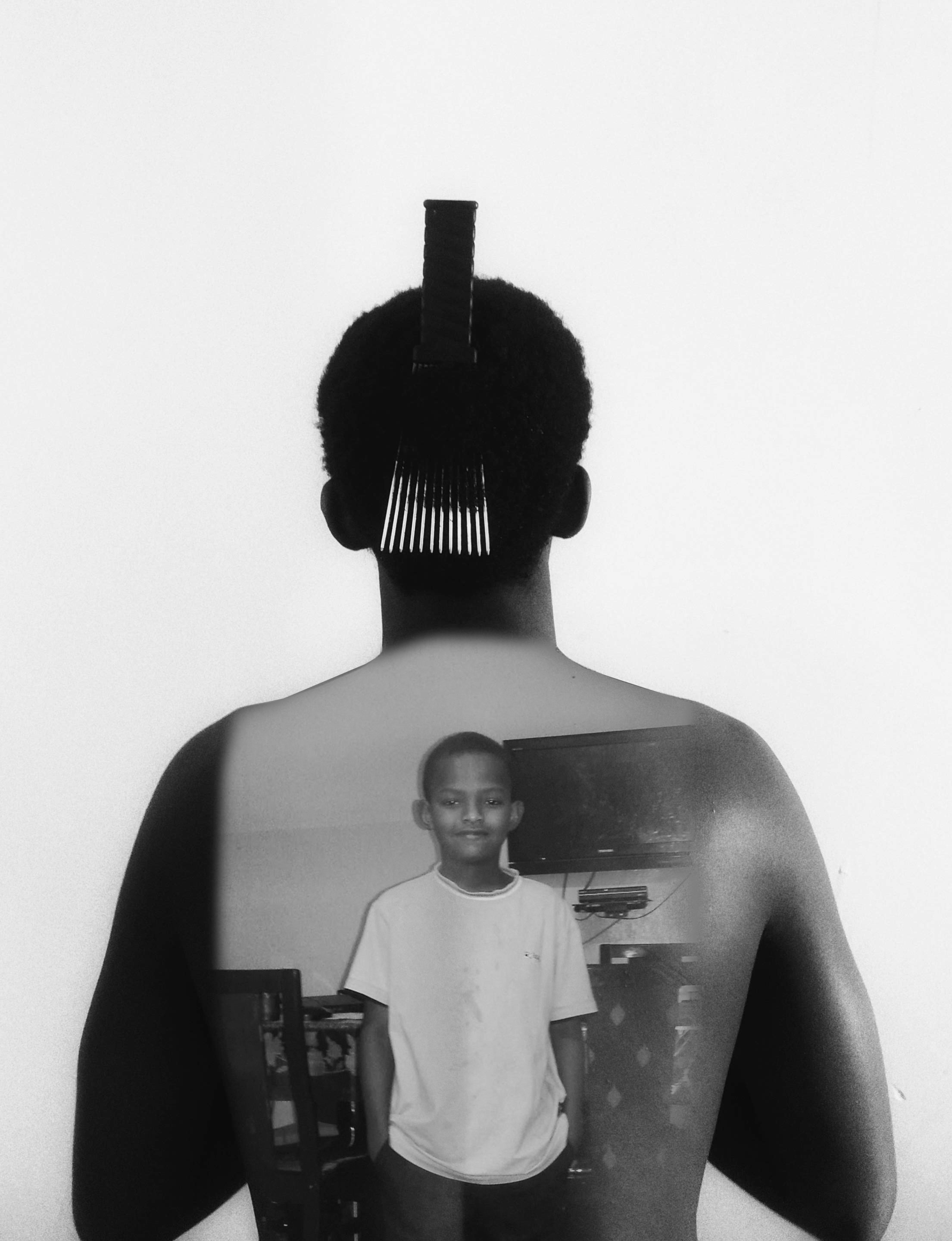

Homeless/lost childhood

I titled this self-portrait “Homeless” because it was taken soon after I had to leave the house where I was staying in Kampala. I double-exposed it with a photo from my childhood in Qatar, taken in 2013, to contrast two very different moments in time.

Before the war, as a kid, home wasn’t about paying rent or providing for the household – I didn’t have those pressures. My childhood version of home was simply a place of relief, free from worry. But as an adult, that old concept of home no longer exists for me.

Generally, Kampala has been less harsh than Juba – maybe because I found a larger Sudanese community here, or because I can photograph more freely, or simply because I have more opportunities to work. It has become a phase of self-exploration, where I have focused on learning as much as I can and figuring out what I want to do next.

Still, often all I can think about and remember is my childhood – a time without doubts, responsibilities, or fear of tomorrow.

Alongside the uncertainty of temporary homelessness, I faced the heartbreaking loss of my little sister, Ruba Yassir, who passed away on 16 December 2024, at just 15 years old.

Ruba – losing you and coping with it was not easy, and sometimes I blame myself for that because your sickness and pain was not cured, and I do not know when I will forgive myself from that.

My experience is just one among millions of Sudanese stories – untold stories of people who have lost their families and been forced to flee their homes. Thousands have died from hunger, and thousands more because they couldn’t afford healthcare. The conflict is still ongoing and growing. All I wish is it to end.

When it comes to the idea of “home”, that is a word I stopped using a long time ago. I’ve almost forgotten what it truly means, but I will keep searching for it, even though I’m pretty sure it will be nearly impossible to find.

For now, I’ve replaced it with other words: “house”, “room”, “hostel”.

Edited by Philip Kleinfeld.