In late October 2023, eight armed men pulled up on motorcycles to the pasture outside the town of Biyanga in central Burkina Faso. Shifting their weapons into view, the militants demanded that the half-dozen assembled herders hand over their livestock.

“They told us we had been paying zakat (Islamic taxes) to the wrong authorities, and demanded 30 years’ worth of zakat to be paid in livestock,” remembers Mohammed Ahmed*, a 53-year-old Fulani herder who has since fled south to neighbouring Ghana.

Ahmed knew these men belonged to Ansaroul Islam, a jihadist insurgency group in Burkina Faso and a member of the al-Qaeda-aligned Jama'at Nasr al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) coalition.

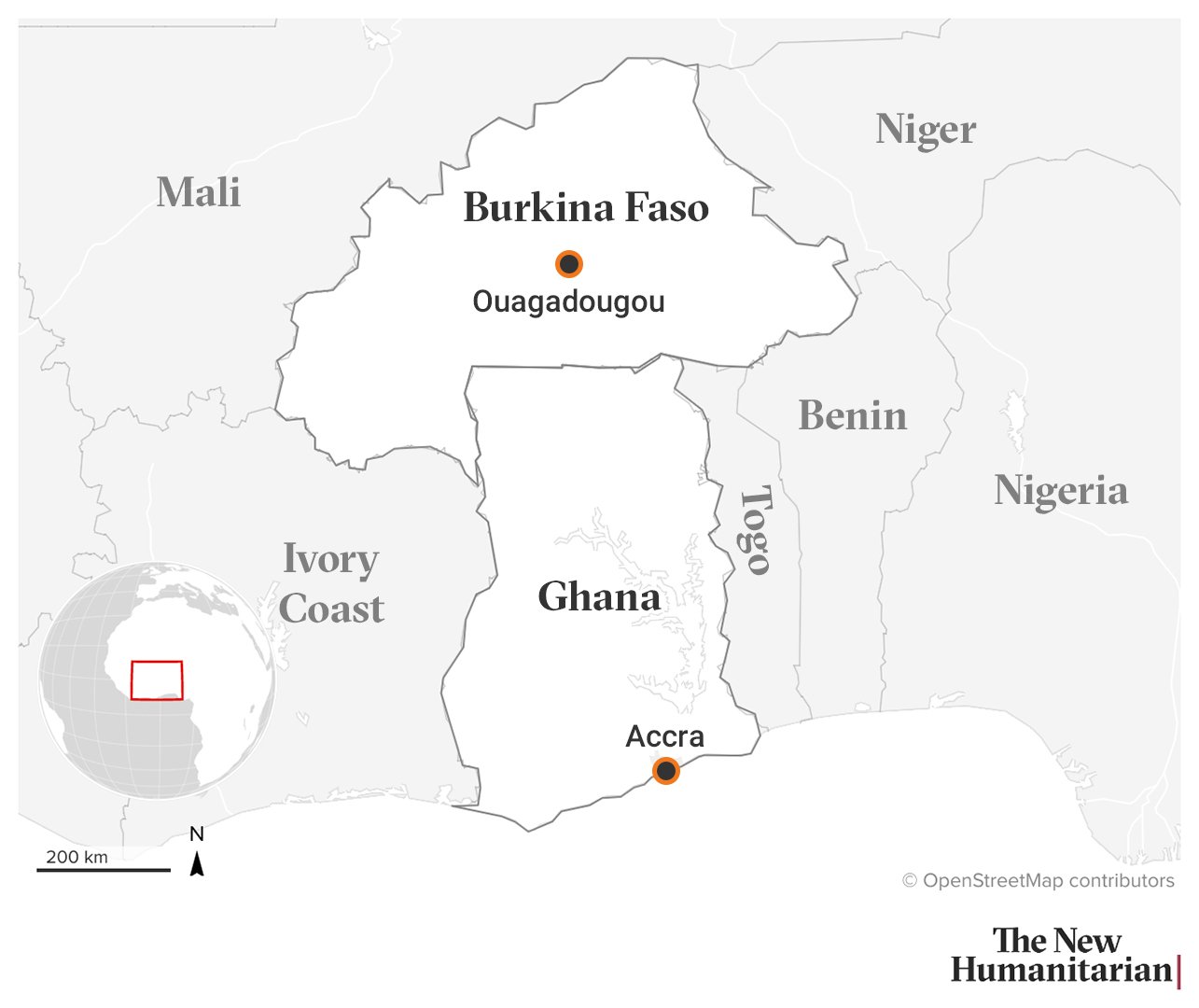

For years, Ahmed and the other herders had heard stories – and watched footage on their phones – as JNIM spread from central Mali into Burkina Faso and then northern Benin and Togo, claiming at least 30,000 lives in their fight against governments and civilians. With this in mind, he dared not resist, and turned over 40 of his cattle to the militants.

“I was so scared I could not sleep for three nights,” he said. “I moved my family to Ouagadougou [the capital], and then came to Ghana with my remaining livestock for safety.”

Cattle and the war economy

Livestock such as Ahmed’s have become an important part of Burkina Faso’s war economy. Since 2017, the Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that over eight million heads of livestock have been stolen in the country.

A new report from the Clingendael Institute that I co-authored with Kars de Bruijne details how cattle rustling in Burkina Faso has escalated alongside the war, with some of those cattle laundered through Ghana’s livestock markets, connecting coastal West Africa to Sahel’s war economy.

Statistics from before the insurgency show that Burkina Faso was once home to 9.6 million cattle, 15 million goats, and 10 million sheep, according to the Ministry of Animal and Fisheries Resources. Livestock production contributed to 10% of total GDP.

“Beyond the meat, dairy products provide nutrition and income for women. Farmers use the manure to fertilise their fields. The skins are processed into leather. These are very important contributions to the rural economy.”

The bulk of this livestock was held by rural residents, largely as an asset to sell off for cash during hard times. Pastoralist communities, especially the Fulani and Tuareg who comprise around 10% of the population, hold a disproportionate share of livestock and play crucial roles in the larger livestock sector.

“Beyond the meat, dairy products provide nutrition and income for women. Farmers use the manure to fertilise their fields. The skins are processed into leather,” explained Hamidou Diallo, permanent secretary of the Network of Pastoralists in Sahel and Africa in Burkina Faso. “These are very important contributions to the rural economy.”

Livestock exports, mostly to coastal countries to the south, also represent an important source of income for the country. In 2017, Burkina Faso’s official live animal exports to Ghana alone were worth nearly $1.5 million, according to figures from the World Bank. These animals are sold to cattle dealers and butchers at livestock markets in Burkina Faso who transport the animals to Ghana for slaughter, or sell them on to urban hubs in southern Ghana for a larger profit.

Ayinbono Jeffery Endinene*, 58, was born and raised in Bolgatanga in northern Ghana in a family of butchers, a hereditary caste in parts of West Africa. Endinene learned from a young age how to appraise livestock and accompanied his father on trips to Burkina Faso to purchase cattle at regional markets and from fellow butchers. Sometimes they would bring the livestock back to Bolgatanga to slaughter there, sometimes they would sell them further south where they fetched a higher price.

“In the past, there was sometimes stolen livestock in the market,” he told The New Humanitarian, referencing the cross-border bandits that have long plagued the frontier. “But it was small amounts, and not frequent. However, since the war began, everything has changed.”

Cattle rustling has been a feature – and at times a driver – of conflict in the Sahel for centuries. When JNIM was formed in 2017, the contingent from central Mali was composed primarily of Fulani herders who had been drafted into jihad after first taking up arms against bandits and rustlers. In Burkina Faso, the group was able to expand into eastern and southern parts of the country by cooperating with – and later co-opting – bandits and cattle rustlers. As militants solidified their control over rural areas, taking “taxes” from communities in the form of livestock, similarly to Ahmed’s experience, has become an important part of the group’s financing strategy.

However, JNIM militants are not the only armed men stealing livestock in Burkina Faso. As insecurity spread, many communities formed self-defense groups, which were formalised in 2019 as the Volontaires pour la défense de la patrie (VDP). Some individuals in the VDP have gone rogue and have been accused of targeting Fulani communities, claiming that they sympathise with the insurgents, pushing them off their land, and seizing their livestock. This escalated following the expansion of the VDP in late 2022, leading to the displacement of entire rural communities.

While some rogue VDP steal livestock for personal gain, JNIM militants manage a more sophisticated and lucrative operation. From their forest bases in Burkina Faso, they collect stolen livestock and then sell it back into the legal livestock market to finance their operations. In northern Burkina Faso alone, JNIM was reportedly making between 25 and 30 million CFA ($44,500 to $53,400) per month from rustling in 2021, according to a 2023 report by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime.

“With the price they gave, we knew it had to be stolen”

The advantage of buying stolen livestock is the price, according to Kaderi Bukari, a professor at the University of Cape Coast who specialises in peacebuilding in the Sahel. “Rustlers sell very cheaply because they are in a hurry to dispose of the cattle,” he explained. Plus, the proceeds are almost all profit, as they stole the animals instead of raising it themselves. Given these incentives, “the butchers are the best to sell to, because butchers will immediately slaughter and sell it, so you cannot trace the cattle.”

However, how and to whom the rustlers sell has changed with the course of the war.

“It was around 2019 that I started hearing that large numbers of stolen cattle were being sold into Ghana,” Endinene recalled. In this earlier stage of the conflict, insurgents could visit cattle markets in Burkina Faso and sell directly to dealers and butchers, who either slaughtered right away or transported the livestock to sell elsewhere.

However, following the escalation of the violence in late 2022, insurgents have had more difficulty visiting centralised markets. With the mass displacement of Fulani communities, they also had to start working with a more diverse group of intermediaries. Today, they increasingly rely on a small group of non-Fulani Burkinabè cattle dealers and butchers to facilitate the sale of their stolen livestock.

This was the period when Endinene’s Burkinabè butchers began to offer to sell him rustled animals. “They did not tell me directly it was stolen,” he said, “but from the price they gave me, I knew it had to be.”

After finalising the deal, the cattle are loaded into a truck in the forest in the dark of night and driven to the border with Ghana. A herder then guides the livestock over hilly terrain where they are met by another truck with Ghanaian license plates. If there are only 10-15 stolen cattle, he said, he will sell them either directly to local butchers, restaurant owners, or, less frequently, in nearby cattle markets. However, if the shipment is between 30 and 60 head, he will send them in a large lorry to the capital Accra or the port city of Takoradi.

Another Ghanaian cattle dealer The New Humanitarian spoke with said that in the last year, seven of his contacts in Burkina Faso had disappeared.

Today, Endinene estimates that about half of the livestock he has bought are stolen. “The advantage is the price,” he told The New Humanitarian. Sometimes he can purchase a cow for the equivalent of $234, and then sell it in Ghana for $700. “Even when the economy and exchange rates are bad,” he explained, “you can still make a living.”

While the margins on stolen livestock are good, trading in this contraband still carries significant personal risks. Following the disappearance of Burkinabè cattle dealers late last year, Endinene says he has avoided travelling to Burkina Faso and instead conducts business via telephone.

Another Ghanaian cattle dealer The New Humanitarian spoke with said that in the last year, seven of his contacts in Burkina Faso had disappeared – allegedly at the hands of the authorities cracking down on the trade.

When asked whether buying stolen livestock contributes to the conflict in Burkina Faso, he reasoned that “the owners of these cattle have already been killed. They will not get their cattle back. The [insurgents] will sell the livestock anyways, so we might as well make a small profit to improve our lives.”

A regional threat – and regional solutions

While intermediaries like Endinene claim selling stolen livestock is a victimless crime, our research suggests that these networks fuel conflict in Burkina Faso and could pose a risk to Ghana and other neighbours.

The proceeds from selling stolen livestock allow JNIM to acquire crucial supplies such as fuel and food as they continue to wage war in Burkina Faso and launch attacks in Benin and Togo. While insurgents have not attacked Ghana, the violence directly on its border fuels instability through displacement of communities, market closures and light weapons proliferation.

Furthermore, the smuggling of stolen cattle into Ghana also facilitates local corruption. In addition to paying veterinarians for transit paperwork, some intermediaries are said to either work with, or pay off, police to transit livestock across the country unhindered.

Finally, while JNIM militants themselves are removed from the actual selling of livestock in Ghana, their participation in this illicit market system could grant them a foothold to build deeper networks in the future, if they so choose.

Regional governments appear to be aware of the threat and are beginning to take steps to address the issue. Late last year, the Burkinabè minister of security and the divisional commissioner of police visited the cattle market in Fada N’gourma to discuss how to prevent insurgents from accessing it.

In some cases, the government has temporarily closed smaller markets near the border and arrested and allegedly disappeared intermediaries working with insurgents.

As Endinene testified, this has already made it more difficult for Ghanaian dealers and butchers to access the Burkinabè market.

In Ghana, the administration of President John Mahama has signalled its desire to deepen relations with its northern neighbour. Mahama visited Ouagadougou in March and created a special envoy to liaise with the Association of Sahelian States, of which Burkina Faso is a founding member.

The special envoy has indicated via social media his desire to increase counter-terrorism cooperation with Sahelian states, and there is scope for Ghana and Burkina Faso to jointly address cross-border cattle smuggling.

While this is all welcome to Diallo, the permanent secretary of the pastoralist network back in Burkina Faso, he is already thinking of how to revive the country’s livestock sector.

“If we had peace tomorrow, it would still take five to 10 years just to stabilise the country’s livestock population,” he estimated. But until then, he added, “we must stop the pillage of one of Burkina Faso’s key resources.”

*Names have been changed for security reasons.

Edited by Obi Anyadike.