Intense fighting broke out in 2014 near Svetlana Kozlova’s apartment in Donetsk, where she was raising her newborn daughter. She didn’t want to leave. But when a mortar attack blew out the windows, she packed her family’s bags and they fled for their lives within the hour.

Five years later, she is one of 300 people still living in grey container blocks erected on the outskirts of Ukraine’s second city of Kharkiv to house – supposedly temporarily – the flow of internally displaced people (IDPs) escaping conflict in the country’s eastern Donbas region.

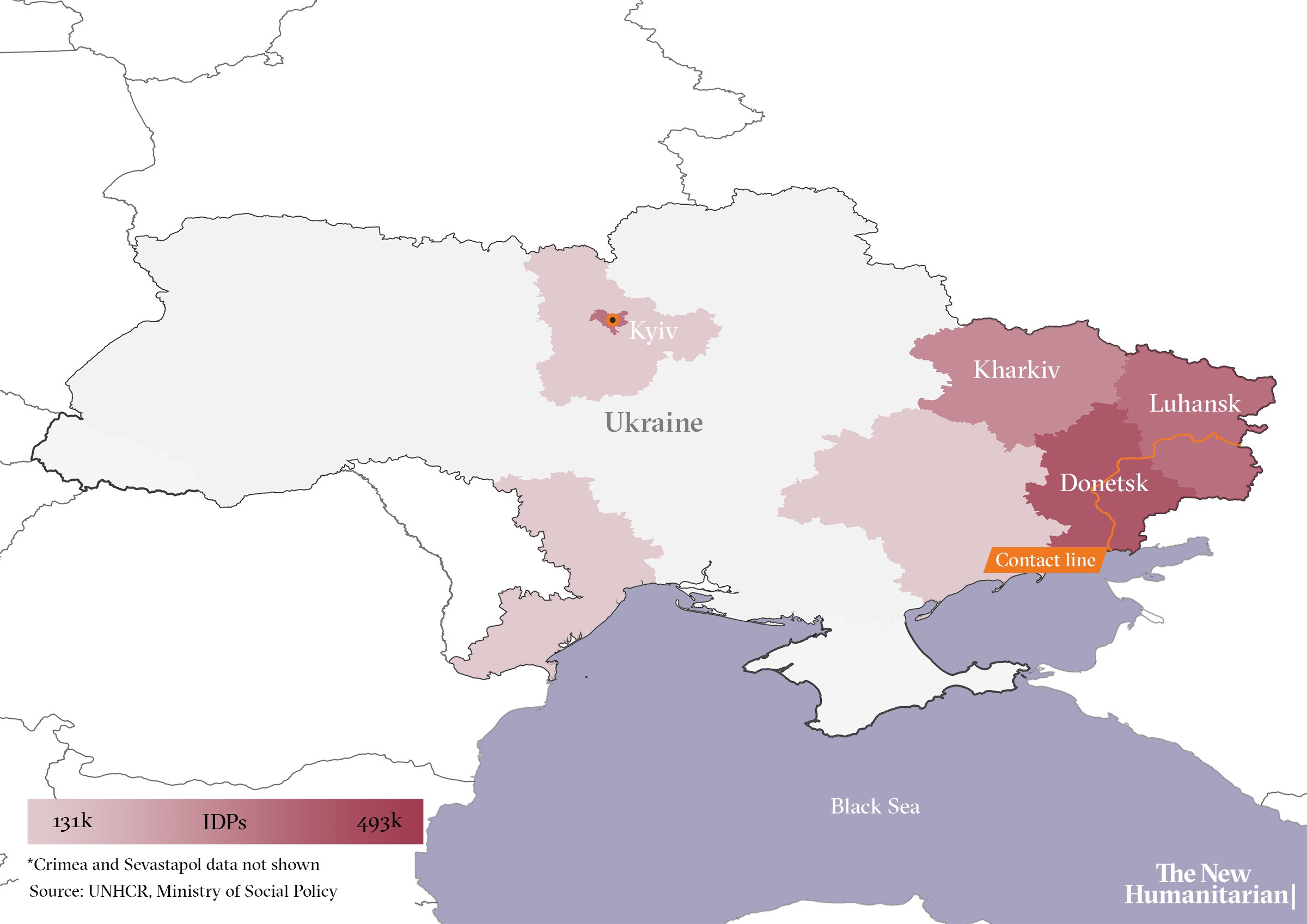

Russian-backed armed separatists seized swathes of Donetsk and Luhansk – the provinces that make up Donbas – in the wake of the 2014 Euromaidan protests that saw president Viktor Yanukovych flee the country and the subsequent annexation of Crimea by Russia.

The conflict between the government and the forces of the self-declared Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics has claimed 13,000 lives – including more than 3,000 civilians. It has also wounded 30,000 people, and left 3.5 million in need of humanitarian assistance.

Kharkiv bore the brunt of the initial exodus, with 250,000 people coming through in 2014. With no resolution to the conflict in sight, displacement is becoming increasingly protracted for 130,000 IDPs still unable to return from the province to their homes in the Donbas.

Nationally, 1.4 million IDPs from Donbas, Crimea, and Sevastopol are registered by the Ministry of Social Policy of Ukraine, with the largest numbers in the regions of Donetsk, Luhansk, Kyiv, and Kharkiv.

While the majority of those displaced across Kharkiv province live in rented apartments, families residing in the modular grey container homes within Ukraine’s second-largest city live under fear of eviction from a site that has long passed its use-by date.

“Normally, you do not live in these conditions for such a long time,” said 54-year-old Natalia Yefimava, who has been living in the block since the separatists occupied Donetsk in 2014. “This is a temporary solution, but it has turned permanent. It’s enough for survival. We got so used to it that, at times, it feels like it’s for life.”

With her wheelchair-bound adopted daughter, finding private accommodation has proved impossible. Even if they did, Yefimava says the 6,000 Ukrainian hryvnia ($238) disability pension they receive each month wouldn’t cover the rental of an apartment for their family of three. When families have been offered alternative housing, it has often been in the form of beds for the infirm in hospices or hospitals.

Lack of housing, income, and employment opportunities remain the biggest issues for IDPs trying to integrate, according to a March 2019 survey by the UN’s migration agency, IOM. Only half of those surveyed said they felt integrated into local communities.

“The IDP town [in Kharkiv] was supposed to house people for a few months,” said Yuri Shparaga, head of the Social Security Directorate for the provincial administration. “It was not meant to withstand the elements for years, so the roofs and walls are crumbling. Now, we face accommodating these people permanently, because many cannot return to the occupied territories. Nobody expected the war to last this long.”

‘It’s hard to find a job if you’re not settled’

Many IDPs remaining at the Kharkiv block have high needs – from single mothers to the disabled or the elderly, or the 130 children growing up on site.

Kozlova, 40, is one of the minority of residents who is working, hand-sewing clothes from a corner of the two-cubicle home her family of five recently moved into after years in a single 13-square-metre room. Her salary, combined with her husband’s pay for ad hoc labour, just covers their electricity bills.

“If we didn’t have this place, we would have had to go back [to the occupied territories] because renting here is expensive,” she said. “We are even ready to move out of the city into a rural area for a permanent place where we wouldn’t have the risk of eviction. The main difficulty is starting anew, as it’s hard to find a job if you’re not settled.”

Her 16-year-old son struggles to commit to future plans because of the question marks over his future. “It’s very difficult for children to move all the time,” said Kozlova. “My son doesn’t know if he should start anything, because we might have to move at any time.”

For the larger proportion of IDPs across the region who rent, housing costs remain a major burden.

“We have a semi-basement apartment, but because of the demand, it is the same cost as a normal apartment,” said Irina Slyucareva. The 51-year-old pre-school teacher from Horlivka in Donetsk is adjusting to life in a small Kharkiv district village near Izyum with her nine-year-old son. “Housing conditions are bad, but we are thankful, after living [crammed together in one room] in a hotel for a year.”

Vartan Muradian, assistant field officer in Kharkiv for the UN’s refugee agency, UNHCR, told The New Humanitarian that a comprehensive programme of affordable housing solutions was a very acute need for the province.

“IDP households residing in rented accommodation feel highly insecure as [inadequate] local markets… and continued discrimination – on the basis of the area of origin, persons with disabilities, or families with many children – make it difficult to find appropriate living conditions for a reasonable price,” he said.

New projects

The government launched a national IDP strategy at the end of 2018 to move from dealing with primary needs to defining long-term solutions. However, its impact has been limited, partially due to its lack of inclusion in the current budget, said Valijon Ranoev, from the UN’s emergency aid coordination body, OCHA, in Ukraine.

“While some progress has been made, large numbers of IDPs remain in protracted displacement, and overall income for IDPs remains below the minimum wage and average income,” he said. The average monthly IDP household income is half the national Ukrainian average.

At the local level, projects are underway to rehouse and support IDPs permanently. In Izyum, a city of 50,000 with 7,000 registered IDPs, a former Soviet-era kindergarten has been refurbished into dormitory housing that will open in October for IDPs and veterans.

“Lots of people are very much anticipating this opening, so it’s very important,” said Kosenko Oleg, the 35-year-old project manager.

Himself an IDP from Pervomaisk in Luhansk, Oleg spent two months hiding from fighting in a basement with his family before escaping to Izyum four years ago.

His project is one of many developments in the country being funded by the European Investment Bank (EIB) to support areas that have had the highest influx of IDPs.

Through the EIB’s emergency credit programme for Ukraine, Kharkiv has 13 projects underway to increase capacity at schools and hospitals to cater to the growing IDP population, including new surgical, ophthalmology, and cardiology wards in the city.

Kharkiv’s Social Security Directorate is also in discussions with funders to develop 75 new houses to rehome families living in the outdated units.

“The IDPs have the same basic rights as every person in Ukraine and we need to supply them with the facilities,” said Shparaga.

But the official said the displaced shouldn’t be given preferential treatment over local families also waiting for social housing. He said the administration was seeking external funding to house the displaced so the existing budget could still be used to support local families.

While many IDPs are resigned to settling permanently outside Donbas, others still hope to return to their own homes one day.

Kozlova would return if and when the war ends. For now, though, she remains in purgatory, waiting to see if her family will be moved from their Kharkiv container home. “Here,” she said, “I [have come to] understand the true meaning of ‘live for the day’.”

(TOP PHOTO: Some 130 children are growing up at the IDP centre in Kharkiv, five years into the conflict.)

lf/ag