Shwe Maung first heard the shots at around 1 a.m. on 9 October.

At the time, the 23-year-old fisherman was in his village on the outskirts of Maungdaw Township in the north of Myanmar’s Rakhine State.

Neighbours were roused from sleep. Phonecalls were made. The shooting continued for hours.

“We didn’t really know what was happening,” he said on Wednesday, sitting in a tent at a shelter full of ethnic Rakhine people in Sittwe, the state capital, about a five-hour boat ride south of Maungdaw. “And all of us were really afraid.”

His village, Mrauk Paing, is a 15-minute drive from one of three border guard posts attacked in the early hours of that day. Myanmar’s government initially stated that the suspects belonged to a previously-unheard-of Islamist militant group with ties to the Pakistani Taliban, but later said all the details were not known. Muslim organisations in Myanmar have condemned the attacks.

The assault killed nine police officers, according to the government, and set off a manhunt that has reportedly resulted in the deaths of five soldiers and dozens of ethnic Rohingya. The attacks and the violent response – which has generated reports of widespread abuses of civilians – have further destabilised Rakhine state.

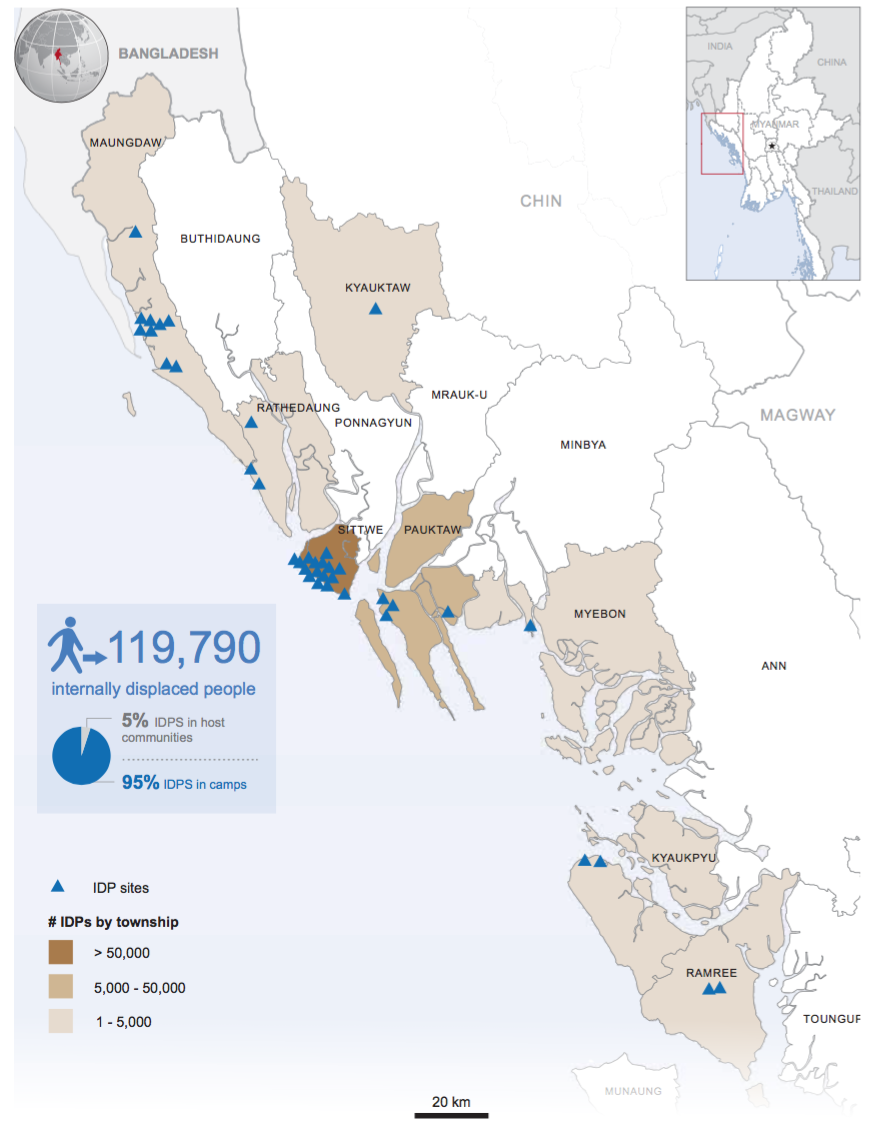

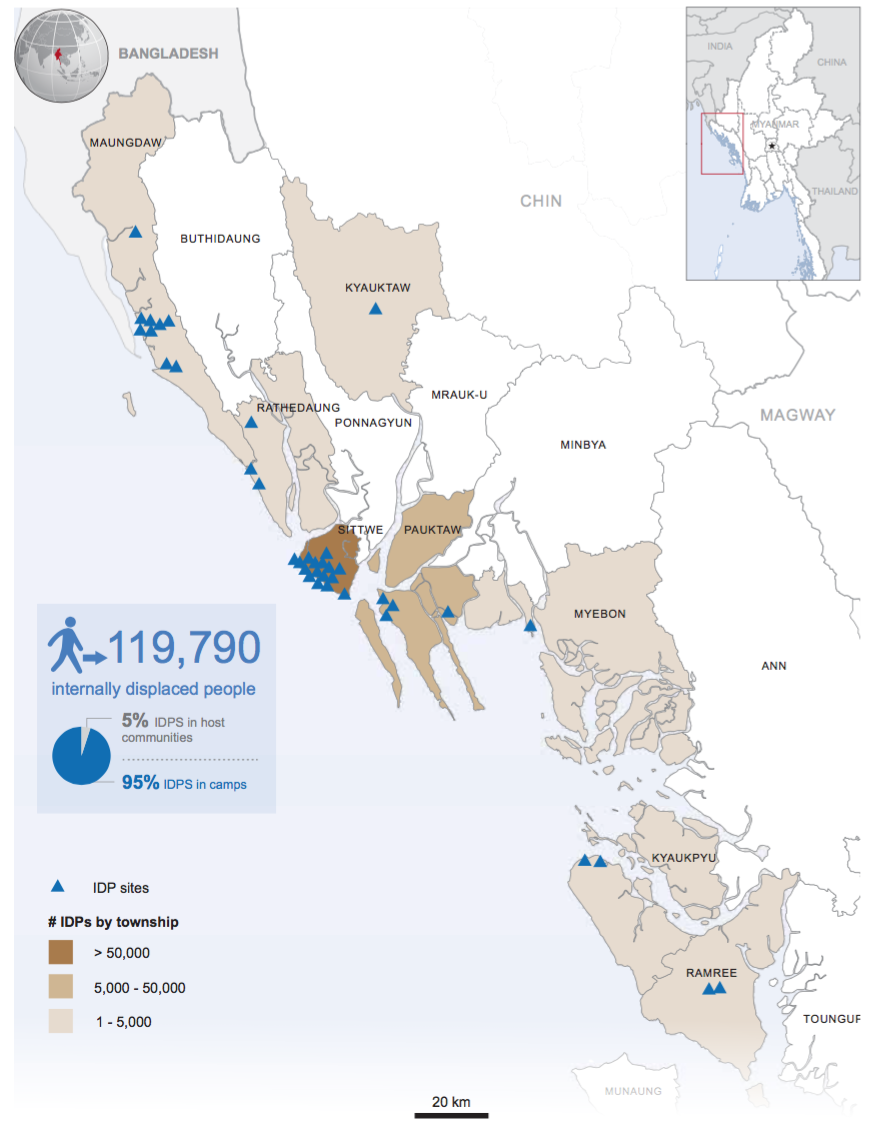

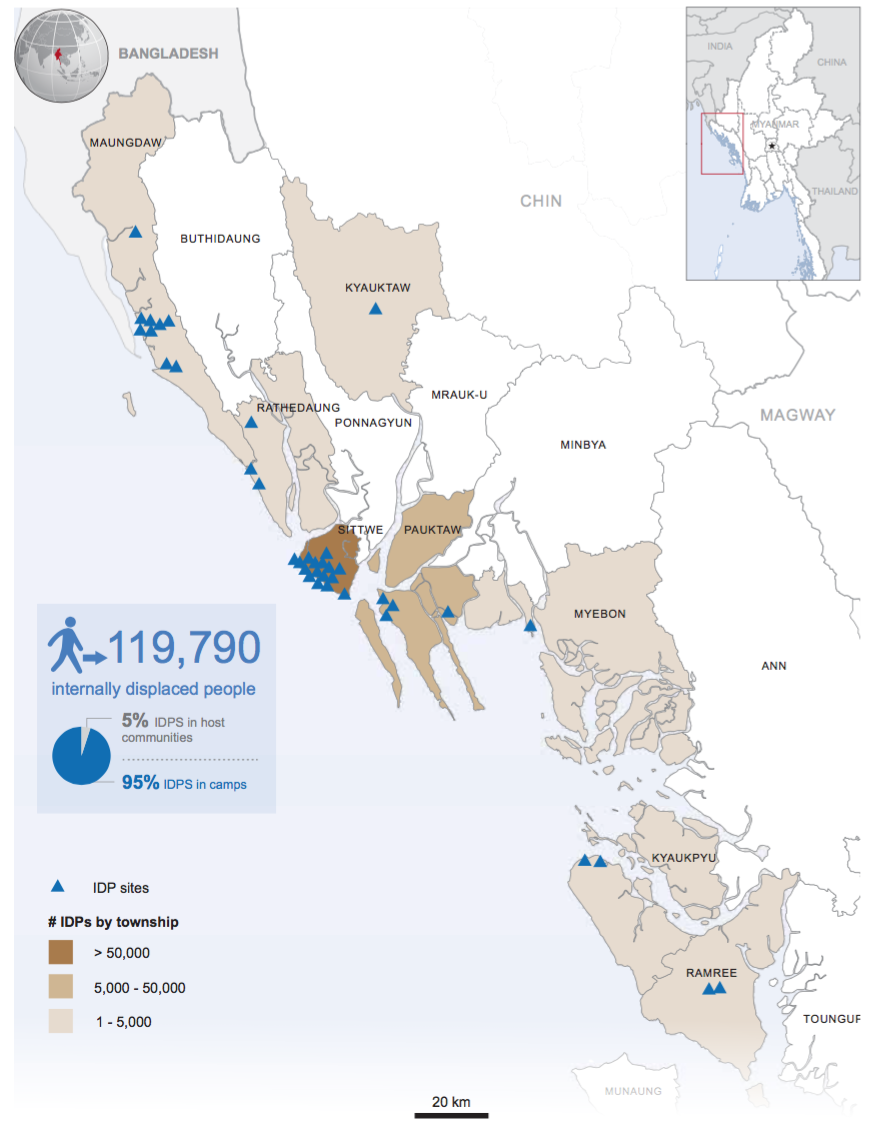

The coastal state on the western fringe of the country is mostly populated by Rakhine Buddhists, but the areas around Maungdaw, which borders Bangladesh, are predominantly Rohingya Muslim. One of Myanmar’s most volatile regions, intercommunal violence exploded in Rakhine State in 2012 when about 140,000 Rohingya were burned out of their homes and then relocated to displacement camps, mostly outside Sittwe.

Almost 120,000 Rohingya are still in camps today, along with a much smaller number of Rakhines. But even Rohingya who remain in their villages live under apartheid-like conditions, mostly stateless with their movements tightly restricted and limited access to medical care and education.

The violence over the past couple of weeks has displaced another 15,000 Rohingya and 3,000 Rakhines, according to aid agencies and Human Rights Watch. The rights group has called on the government to allow humanitarian groups access to Maungdaw to deliver aid.

In the wake of the attacks, more than 1,000 displaced Rakhines made their way to Sittwe, among them Shwe Maung and his family.

Night of terror

No one knew what was happening in the confusing first hours of 9 October. Shwe Maung’s community took up sticks, knives and slingshots and established a security perimeter.

The community watch stayed up until after sunrise. Once they learned more about what happened they grew concerned for their own safety and arranged car rides out of the village and boat rides down to Sittwe. More than two weeks after that night, Rakhine Buddhists who fled Maungdaw are still hunkered down in a miniature tent city inside Sittwe’s only sports stadium. Others are in makeshift shelters and monasteries.

Hla Win, a member of a Sittwe community organisation that is coordinating the relief efforts with support from the government and local donations, said the authorities are attempting to get them back to their homes “as soon as possible”.

Although some have started to return, many are too scared to make the journey, according to interviews with several people sheltering in the stadium. They receive updates from neighbours who stayed behind to guard property.

“Until now, that situation is unstable,” said Shwe Maung. “We have to wait until it is stable.”

Fuelling tensions

Some of the official statements from the Myanmar authorities are unlikely to have helped calm the situation.

On 18 October, Home Affairs Minister Lieutenant General Kyaw Swe suggested it was important for Rakhine Buddhists to return so they would not become even more outnumbered by Rohingya Muslims.

“If our ethnics leave their own places, [they] will replace them in those free spaces. I don’t want this to happen,” he told reporters. “For us, one man only marries a woman. For them [Muslims], a man marries four women. If one is breeding 10 children, there can be 40 people in a family. So I want our ethnic people to love their own places.”