Two months after one of the strongest earthquakes in Morocco’s history killed nearly 3,000 people and destroyed entire villages in the High Atlas Mountains, women in Indigenous Amazigh communities are finding it particularly hard to recover.

Of the 500,000 people displaced and the many more impacted by the 8 September earthquake, most are Amazigh – an Indigenous group that traces its presence in Morocco back to before the Arab and Islamic conquest in the 7th century.

For many Amazigh women, the loss of homes and workshops in the 8 September disaster meant they also lost their livelihoods, as this is where they produce the rugs and crafts they sell to support themselves and their families.

In early October, the government said it had started disbursing 2,500 dirhams ($245) in monthly assistance to each affected household as part of a year-long cash relief programme. It also promised up to 140,000 Moroccan dirhams ($13,700) for each destroyed home and 30,000 dirhams ($3,000) to 50,000 households affected by the quake.

However, none of the survivors The New Humanitarian spoke to in early October said they had received any compensation, and the aid and support that has arrived has been insufficient, especially for women.

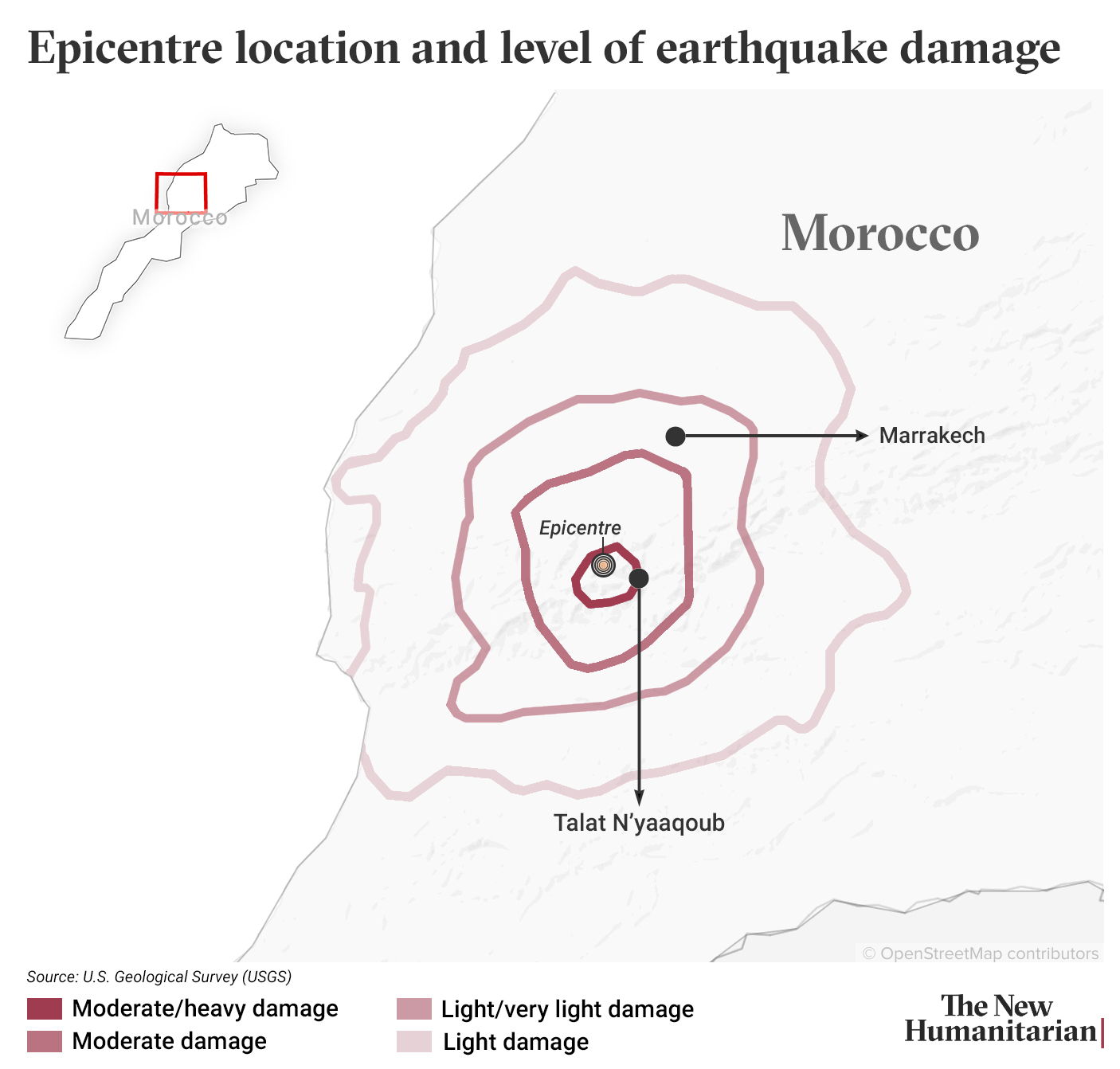

In Talat N’yaaqoub, close to the epicentre of the earthquake, 100 kilometres south of Marrakech, 27-year-old Najat, who preferred to give only one name, was living in a dirty blue plastic tent, surviving mainly on canned food.

Two weeks before the 6.8-magnitude quake struck, Najat had given birth to her second child. She was struggling with what she called “severe sadness”, but was glad to have recently learned from doctors that it had a name: postpartum depression.

“I felt a bit of relief because I understood that my case is normal and I was not going crazy,” Najat told The New Humanitarian.

However, since the earthquake, Najat has had trouble making the two-hour journey along mountain roads to the military hospital for treatment. Her husband has also left to find a job in Marrakech — his small mechanic shop in their home village of Idni was destroyed by the earthquake and the family doesn’t have the money to rebuild.

Najat held her other child, a three-year-old, in her arms as she stood in front of the toilet of a school that had been converted into a public shower. Several other women waited in line with their children for their turn to bathe with buckets of water. Najat was still waiting for government compensation, and she wasn’t aware of any other support to help them rebuild.

Despite announcing an $11.7 billion reconstruction plan in late September, the authorities are yet to provide details of any shorter-term plans to help thousands of displaced people like Najat, who had to cope with heavy rain and storms that hit the region in mid-October.

By the end of October, affected communities had started organising protests to call out what they said were the government’s unfulfilled promises.

The need for gender-inclusive aid

Estimates vary about the number claiming Amazigh heritage, with some putting it as high as 70% of the Moroccan population of 38 million. After Morocco regained independence from France in 1956, Moroccan nationalists envisioned a state with a homogenous language, religion, and ruling dynasty: Arabic, Islam, and the King, respectively.

Under this vision of a united Arab and Islamic nation, Amazigh culture was often repressed, and didn’t gain official state recognition until 2001. In 2011, the Moroccan monarchy announced a new constitution that made the Amazigh language (Tamazight) an official language. The announcement came amid the “Arab spring” protests in Morocco, in which Amazigh activists played a prominent role.

However, Amazigh communities remain marginalised, and their homes in the Atlas and the Rif mountains are plagued by poverty and poor infrastructure.

Yasmina Benslimane, a Moroccan feminist activist who is the founder and co-director of the NGO Politics4Her, underlined that 100,000 children and 4,000 pregnant women were affected by the earthquake.

“Authorities should collaborate with the local community, and mainly women, to understand their needs and to make sure the financial aid is gender-inclusive,” Benslimane told The New Humanitarian.

This, according to Benslimane, would include specific healthcare for women, including menstrual care, mental health assistance, and more female aid workers to help women in the camps since in Morocco’s conservative culture women are discouraged from talking to men outside their family.

Back in her tent, Najat nursed her newborn and made a pot of mint tea as she spoke about her worries. She recalled her surprise at receiving a donation bundle from volunteers that was supposed to be essential items but didn’t contain even one pack of menstrual pads.

“All women here were surprised. Not one single package of pads,” said Halima, a woman who joined her for some tea. “Just no one thought about us apparently.”

With aid, new worries

While the assistance – food, hygiene kits, blankets, clothes – that government agencies, citizen volunteer groups, international NGOs, and foreign charities have brought into the affected villages has offered the women hope, some have come with different intentions.

“A fancy car came with well-off people asking if we have girls who want to work as maids; some others asked us if we have girls for marriage,” said Halima, who also preferred to give only one name. “It’s disgusting.”

After the earthquake, misogynist posts proliferated online calling on men to head to the affected villages to find a “child bride”. Some people even took pictures with girls in the camps and posted them on Instagram with similar messages.

On 25 September, a Moroccan court sentenced a male student to three months in jail for sharing posts on social networks urging men to prey on young girls who had lost their parents in the earthquake.

Several Moroccan NGOs have called on the authorities to protect the earthquake victims and to criminalise “child marriage”.

Morocco's 2004 family code was aimed at increasing women’s rights and raising the minimum age for marriage from 15 to 18. However, girls can still legally marry below the age of 18 with the consent of a guardian and a judge. If a guardian claims they don't have the financial means to take care of a female ward, the judge can rule in favour of marriage.

Morocco's King Mohammed VI has declared that children orphaned by the quake are “Wards of the Nation”, putting them under the protection of the state. This is supposed to ensure the individual’s welfare, safety, and overall well-being.

Children robbed of futures

Today, Najat is more worried about her sister Hassna, 15, who dreamed all summer about attending the high school in Talat N’Yaaqoub, only to see it in ruins a few weeks later.

“She is 15. I am not sending her alone to another city,” said Najat. “But, it’s sad because I always wanted her to have the education I did not have.”

The High Atlas region’s lack of infrastructure and key institutions – it is known locally as the forgotten Morocco – limit opportunities. Its mountainous terrain makes access difficult.

While the Ministry of Education has built primary schools in most of the country’s remote areas, many teenagers still have to travel hours to attend high school.

In 2000, the Mohamed V Foundation, a state-affiliated charity, launched the Dar Al-Taliba programme to curb school dropout rates among girls in rural areas, and education has improved over the last two decades. In collaboration with the Education Ministry and local NGOs, over 6,000 female students benefited from the programme in 2021.

But damage from the earthquake risks hampering that progress.

Over 500 educational institutions and 55 boarding schools were damaged, including the Dar Al-Taliba school in Talat N’Yaaqoub which lies in ruins behind what became a hub for local and foreign aid after the earthquake.

The Education Ministry started transferring 6,000 students in mid-September from the affected provinces to boarding schools in Marrakech so the children could continue their classes, but there have been reports since of overcrowding and abuses.

A way of life under threat

Many women in the Amazigh villages relied on weaving traditional rugs to make a living, express themselves, and preserve their identity.

The earthquake has interrupted all this.

In Lmdint, a village near the southern city of Ouarzazate, Fatima Ibrahimi examined the cracks sneaking across the ceiling of the workshop where she has weaved hundreds of traditional rugs over the past decade.

In Ibrahimi’s village, where Amazigh artisans reside, eight houses were destroyed, and the rest are severely damaged, including the workshop where she and her neighbours wove, tufted, knocked, and painted eco-friendly rugs.

“We have been calling for solutions before the earthquake. No one wants to listen to us.”

The Indigenous community rely on the sales of crafts, as well as agricultural products, to survive. But drought, worsened by climate change, has hit the farming industry hard, while middlemen have been monopolising the sales of local crafts for years.

The Anou Cooperative, a local NGO, has been working to help these Amazigh artisans, mainly women, since 2013. But the earthquake has spawned a feeling of helplessness, amid growing frustration at the government’s failure to address their concerns.

“The state is making efforts, but they are not enough. We have been calling for solutions before the earthquake. No one wants to listen to us,” said Hamza Cherif D'Ouezzan, the managing director of Anou, which advocates for a model whereby artisans would get to keep 80% of the profits.

The Amazigh women The New Humanitarian spoke to still feared for their uncertain future.

Although a government-run account for donations from the public and private sectors have now reached about $1 billion, earthquake survivors still complain that there is no concrete plan for each village. This makes them question the credibility of government promises, especially given recurrent failures to respond to problems in their remote region.

In 2018, a man died in Tahala, in mountainous Amazigh territory, after the snow blocked the road and he couldn’t get back to the village. His death prompted a series of protests about the authorities’ slow response – earlier reports of locals killed in snowstorms in the mountains had already gone unaddressed.

“These are not only the earthquake effects. These are the effects of years or marginalisation of the forgotten Morocco,” Cherif D'Ouezzan said. “The only solution is to end this forgotten Morocco by serious and inclusive work with the local community.”

Edited by Tom Brady and Andrew Gully.