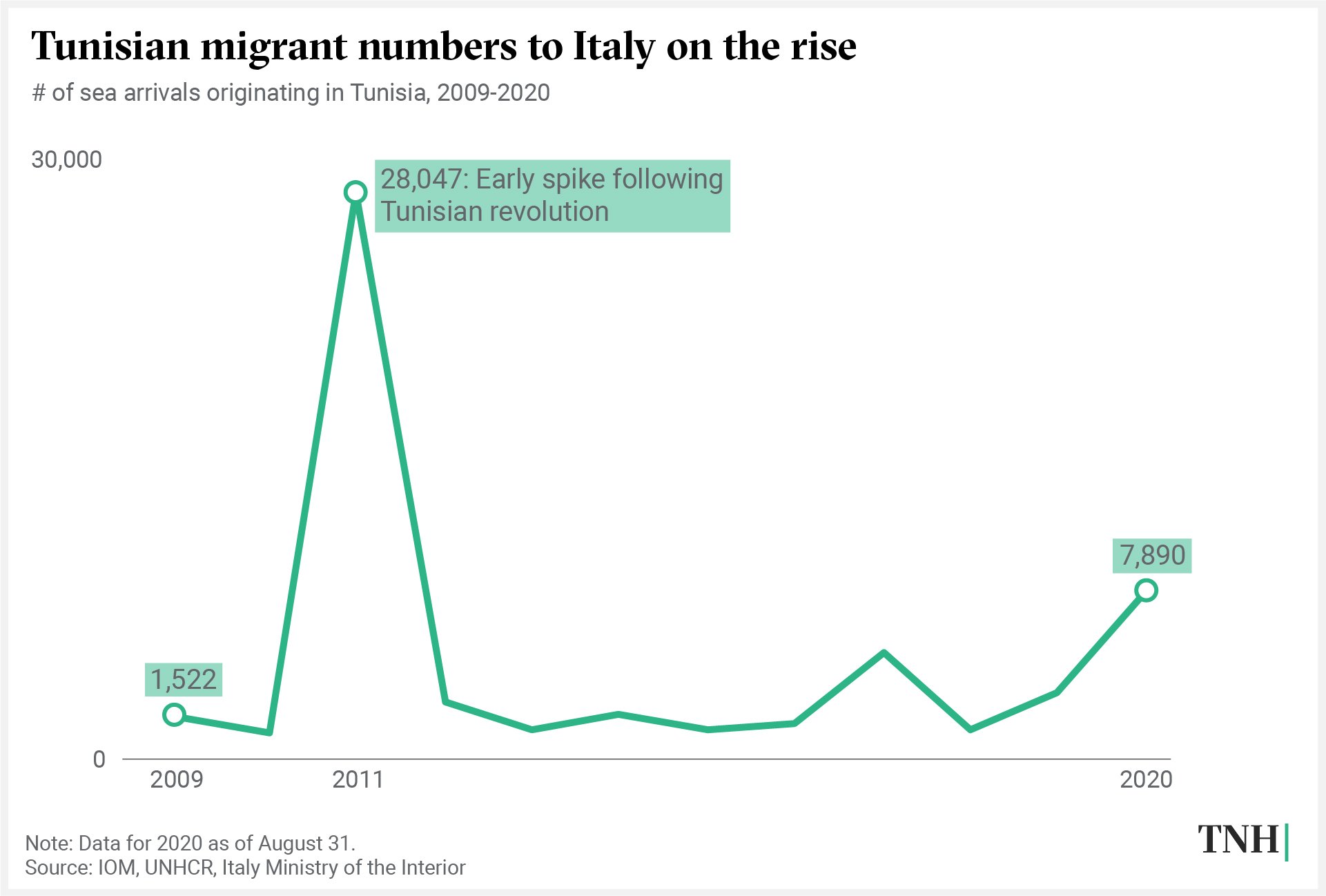

Driven partly by increased hardship as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, almost three times as many Tunisian migrants have crossed the Mediterranean Sea to Italy already this year than did so in all of 2019.

Italy is putting pressure on Tunisia to reduce departures, but the decades-long history of migration between the two nations suggests these efforts may do little to deter Tunisians intent on escaping their country’s long and worsening economic malaise.

The arrival of more than 7,800 Tunisians in 2020 – including over 4,000 in July alone – has overwhelmed the migration reception centre on Lampedusa, Italy’s southernmost island, 130 kilometres from Tunisia’s coast, and helped right-wing Italian politicians stoke anti-migrant sentiment during the pandemic.

Read more → Italy’s Lampedusa: Back on the migration front line

Italian Interior Minister Luciana Lamorgese visited Tunisia at the end of July and met with Tunisian President Kais Saied to express concern over the “uncontrolled flow” of migrants and to pledge support for economic development. Italian Foreign Minister Luigi Di Maio also called for a “new accord” with Tunisia to reduce the number of arrivals.

In the weeks that followed, Italy resumed deportation flights to Tunisia that had been suspended in March due to the coronavirus crisis, and the EU announced an additional 10 million euros ($11.9 million) in funding for the Tunisian Coast Guard to improve migration management.

During a visit to Tunisian Coast Guard units on 2 August, President Saied said that approaching migration solely as a security issue was “insufficient”, and it was time to reflect on the real reasons pushing people to leave. “We need to recognise that in Tunisia we haven’t managed to resolve the problems with the economy and development,” he said.

His comments reflect a scepticism in Tunisia that the migration flow can be stemmed simply by Italy resuming deportations and the Tunisian government cracking down on departures.

“Migrants and smugglers will always find other ways and means,” Romdhane Ben Amor, communications officer at the Tunisian Forum for Social and Economic Rights [FTDES], a non-governmental organisation, told TNH. “Italy and the EU say that they want to support the democratic transition in Tunisia, but the real threat is the social and economic situation. It’s causing violent protests every year. It’s causing people to leave.”

‘The guard of the European maritime border’

In December, it will have been 10 years since the beginning of the Tunisian revolution, which ended the rule of long-time dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali and touched off protest movements across North Africa and the Middle East.

As much as political change, many Tunisians hoped the revolution would open the door to economic reforms and growth. But the economy has floundered since: The Tunisian dinar has lost half its value against the dollar, and the purchasing power of families has plummeted by 88 percent, according to estimates.

The coronavirus pandemic has only deepened the crisis. The economy is set to shrink by 6.5 percent this year, and unemployment has risen from 15 percent to 18 percent overall, reaching 36 percent among youth.

Migration from Tunisia to Italy has ebbed and flowed since the revolution, peaking in 2011 and falling and rising since as the population’s confidence in the direction the country is heading has varied.

Like Libya next door, Tunisia has been a focal point of migration-related funding from the EU. Since 2016, the country has received 57 million euros via the EU Emergency Trust Fund for projects with the direct or indirect objective of reducing migration to Europe.

A small amount of the money has gone to support migrants and refugees in Tunisia. But most was allocated to reinforce border patrol capacity, according to a report by FTDES. As a result, the Tunisian Coast Guard has been “transformed into the guard of the European maritime border”, Ben Amor said.

The Tunisian Coast Guard conducted 481 missions to intercept boats trying to leave the country in the first six months of this year compared to 129 over the same period in 2019 and 224 in 2018. And the number of Tunisians arrested for attempting to leave the country irregularly in 2020 exceeds the number that have arrived to Italy, according to data collected by FTDES.

As the number of crossings have risen, so have the accidents. Two boats sank near to the southern Tunisian coast last week, claiming three lives. In the last week of July, there were three shipwrecks, with one death, 27 people reported missing, and 30 rescued, including one person who had spent four days at sea before the Tunisian Navy found him. The deadliest accident this year was in June, when more than 60 migrants from sub-Saharan Africa drowned after taking a boat from the port city of Sfax.

With the increased focus on migration since July, police also recently started treating people travelling from the interior of the country toward the coasts as suspected migrants, threatening their freedom of movement, Ben Amor noted.

‘It used to be simple’

Tunisians have travelled to Italy in search of economic opportunity at least since the end of World War II, when they went to fill a labour gap. Migration back and forth used to be normal, and relatively easy.

Since the advent of the EU’s free movement Schengen Zone in the 1990s, visas for Tunisians to travel, work, and study in Italy have been harder to come by. “This is what has made irregular crossings much more popular – it is now really difficult to legally get to Europe,” Valentina Zagaria, a PhD researcher at the London School of Economics focusing on migration in Tunisia, told TNH.

Over the last few years, Tunisians have adapted to the security measures put in place to try to stop the crossings, according to fishermen TNH spoke to who have watched the evolution. Departure points shift as they become known and surveilled by the authorities. Arrival points have shifted as well, with some migrants paying double to be taken not to Lampedusa but straight to Sicily, where they are less likely to be picked up by the Italian authorities and deported.

“They now go in boats as small as six metres, and that is dangerous.”

Means of transport have changed too. “Now, migrants have started to use small boats because of the radars,” said Chokri Manai, a 52-year-old fisherman sitting in a cafe along the seafront in the town of Mahrès, referring to a system the EU has sought to incorporate into its regional radar network to prevent irregular migration.

Manai sleeps in his small boat because he is scared of it getting stolen by someone hoping to use it to reach Italy. Since the revolution, he has been approached five times by various “organisers” to drive large boats of migrants to Lampedusa, but this practice of ferrying migrants to Italy has more or less disappeared as security has increased and the metal in the larger boats shows up on the radar. “They now go in boats as small as six metres, and that is dangerous,” he said.

“It’s 100 percent risky,” added Samir Ben Cheikh, 50, another Mahrèsian fisherman. He hadn’t been sleeping well after recently overhearing his 13-year-old son talking about trying to go to Italy with his friends. Ben Cheikh didn’t think the resumption of deportations would put his son and his friends off.

“They will just do it again,” he said. “Before, it used to be simple. I’ve been to France five times [legally]… Now, it is like you are in a cage. The solution is to facilitate the travel, then they can come and go like I did.”

More than 7,000 Tunisians were deported from Italy between 2016 and 2019, according to data collected by FTDES. During that time nearly 16,000 Tunisians arrived in the country, meaning some found ways to stay, or to move on to other European countries. And as Ben Cheikh said, even those who are deported often try again.

Sent back, but tried again

Ali, a 33-year-old decorator and fisherman in the southern coastal city of Zarzis who asked to use a different name, has made the trip several times. The first was in 2016 after his girlfriend at the time refused to get married because her family didn’t think he was economically secure enough.

“Here, you need to have your own house to get married, or you need papers [i.e. European citizenship papers], especially in Zarzis,” Ali said. “Her parents wanted her to marry someone [who had made it to] Germany. That is what gave me the courage to go.”

Ali didn’t have enough money to pay for the journey, let alone a house, but travelled to Lampedusa for free by driving a boat with 12 passengers. Upon arrival, the Italian authorities took them to a migrant centre in Sicily, and 10 days later he was put on a plane back to Tunisia with 79 others.

Back in Zarzis, Ali felt frustrated. The cafés were full of people younger than him; new people that he didn’t know because all of his friends had left. He had a job, but he wasn’t making enough to one day build a house. So when he was approached in 2019 to drive another boat to Lampedusa, he accepted, despite his previous failed attempt.

“There are a lot of stories of people who were deported two or three times, and then the fourth time he succeeded and now he is in France,” he said. “That gave me hope.”

But Ali’s second attempt also didn’t end well. This time, the Tunisian Coast Guard intercepted the boat he was piloting before he could make it as far as Italy. Back in Zarzis, Ali says he doesn’t want to try the journey again, but he still isn’t financially secure enough to get married in his hometown.

As long as Tunisians see their future as blocked in their own country, they will likely continue to attempt to reach Italy even if they risk being intercepted at sea or being sent back if they make it. “[Deportations] are not a problem for people,” Ali said. “People go every year.”

With reporting support from Refki Ben Ali.

lf/er/ag