On Sunday, Colombia holds its first local and regional elections since a landmark 2016 peace deal. The run-up has been marred by violence, much of it linked to the fractured demobilisation of the FARC and the rise of new armed groups that have grown to fill the void.

Another battle, key to the chance of maintaining peace after more than 50 years of civil war, is being waged deep in the Colombian countryside, where former Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) guerrillas are struggling to build new lives after decades of conflict.

“Does this look like a dignified way for people to live?” asked Juan de Jesus Monroy Ayala, 45, motioning at a haphazard collection of shelters fashioned from bamboo poles and plastic tarpaulin sheets. “We sacrifice ourselves in these conditions for peace.”

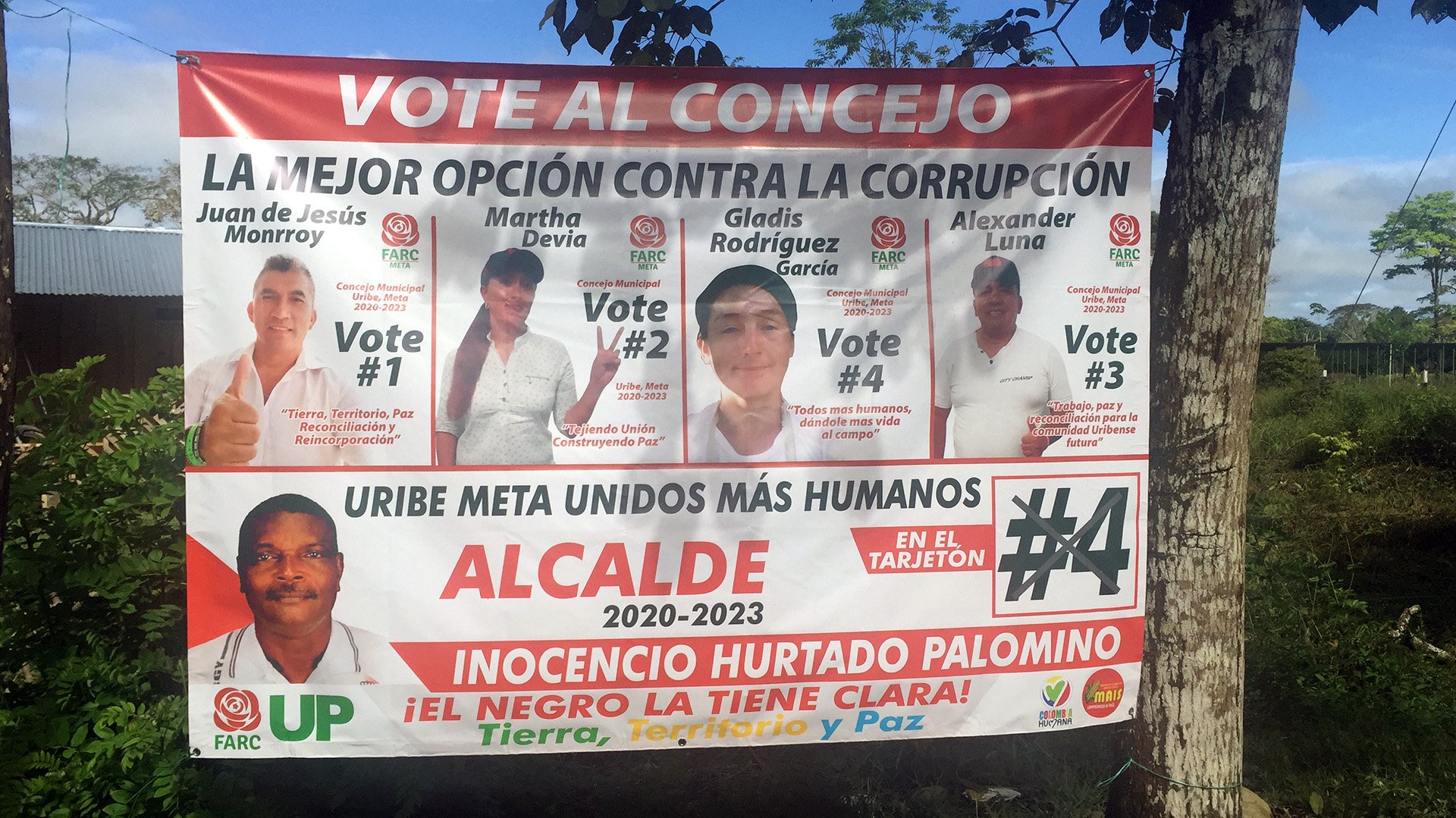

Monroy, a former mid-level officer and member of FARC’s elite guard, is standing to be a local councillor for his small town in Sunday’s polls. For the FARC, now a political party with seats in both the Senate and the House of Representatives, the elections represent a first chance to build support at the ballot box and lay down deeper democratic roots in post-conflict civilian life.

Three years ago, most FARC fighters laid down their weapons, left the jungles where some had spent decades as nomadic fighters, and entered into an ambitious peace process, outlined over 300 pages of agreements signed with the Colombian government.

The Colombian state set up 24 transition camps to help reintegrate more than 13,000 FARC guerrillas into civilian life. But those camps have been mired by sluggish development, grim conditions, and confused leadership from the ex-combatant residents.

Not all the ex-FARC chose to follow the official route. While an increasing number have become disaffected and joined dissidents groups, others have chosen to start up again, peacefully, on their own.

Read more → In Colombia’s Tumaco, the war isn’t over, it’s just beginning

Monroy and 140 other former FARC fighters settled here, outside La Julia, 150 kilometres south of the Colombian capital, Bogotá. They told The New Humanitarian that peace has been harder than they’d imagined and that government promises haven’t panned out.

“Reintegration hasn’t gone as expected and the ex-combatants need support,” explained Naryi Vargas, a researcher at the Peace and Reconciliation Foundation in Bogotá who said Monroy’s group represents one of almost 70 similar ex-rebel communities going it alone.

Implementation of the 2016 accords has had to stumble through a transition of power from president Juan Manuel Santos, who won a Nobel Peace Prize for leading the peace effort, to Iván Duque – elected president last year on a platform of harsh opposition to the accords.

“Reintegration hasn’t gone as expected and the ex-combatants need support.”

The official reintegration camps, and the subsidy programme to help former fighters start over, were supposed to expire in August, but the Colombian government has extended them through 2020 as none of the projects have reached self-sufficiency. Vargas said the move was aimed at reducing the risk of ex-combatants returning to arms.

Last month, a group of senior ex-FARC commanders accused Duque, in a video posted online, of failing to implement the accords, and announced a return to the armed struggle.

Read more → Briefing: Colombia’s new challenge to peace

Although the dissident leaders are believed to command just a few hundred men, Vargas said the move was a blow to the morale of many former fighters who continue to back the peace process despite their struggles and the sluggish implementation of the accord.

Going home

Despite every opportunity to join the dissident guerrillas who have rearmed in the nearby mountains, the community outside La Julia remains committed to starting from scratch as civilian farmers.

The former rebels still rely on those state subsidies: monthly cash payments of about $200 and boxes of various grains and vegetables. They get by from raising a few personal crops, eating fish from the nearby stream, or hunting for wild pigs.

The camp sits 10 hours by truck from the nearest big city and 30 minutes from the nearest small town, on the fringes of a massive wilderness area owned by Colombia’s national parks.

Most residents gathered in this rural backwater because they grew up around here. Monroy never intended to move into one of the reintegration camps set up by the Colombian government when the conflict ended.

When it was time to disband, he wanted to go home and see family he hadn’t seen since he enlisted 20 years before. He rounded up 44 comrades from this rugged region of Colombian cowboy country and founded the JE Cooperative, named after a FARC symbol.

At first they slept on the ground of the small brick structure they had pooled parts of their cash payouts from the accords to buy – for about $11,000, with the surrounding 10 hectares.

The settlement soon grew. Almost 100 other former comrades showed up to join, with about 30 family members. They planted six hectares of rented land with cacao, which represents their greatest hope for economic independence.

“I’d had a different vision of what (the FARC) were,” said Maria Victoria Murillo, 42, recalling when she took up an unusual offer to live and work at the settlement. “I showed up here and fell in love [with it]. They really take care of each other.”

Rebuilding a peaceful life

Many at the JE Cooperative, like 34-year-old Verley Rendon, joined the FARC as teenagers and lived a decade or more as outlaws in the wilderness. Rendon said the processes and paperwork of this new life have been overwhelming for many ex-fighters.

“In the guerrilla, we had no salary,” he said, speaking after he had just lassoed a cow to slaughter for a barbeque fundraiser the next day. “They didn’t teach us about saving money.”

While some of his friends frittered away their government payments, Rendon invested in the cooperative and in renting land to start trading cattle. He now has 10. His dream, he said, is to own his own land and house for his wife and son, who live with him in a makeshift shelter.

“All together we agreed to commit to the accord. Now, they are making unilateral decisions.”

At the camp, Monroy expressed disappointment at his former FARC leaders’ abandonment of the peace process.

“Our feeling is that it’s a violation of the accords and a lack of respect for our word,” he said, shirtless in the wet and sweltering tropical heat. “All together we agreed to commit to the accord. Now, they are making unilateral decisions.”

The 2016 accords aimed to address the rural poverty that fuelled violence and the drug economy. They laid out transformative agrarian reforms that would bring roads, bridges, schools, and economic opportunities to isolated areas that had long relied on coca – the base ingredient of cocaine – as their only source of income.

But most of those changes never materialised, here or elsewhere in Colombia. Critics say land reforms were stalled even before they started due to a lack of government will to tackle entrenched elites and corrupt land ownership.

Read more → Inside Agua Bonita, a model for rebel reintegration in Colombia

Despite dissatisfaction at the state and pace of the peace process, almost everyone at La Julia agreed that life today was better than during the conflict.

One local resident, 35-year-old Fabio Castañera, recalled how he had fled the area in 1995 as open warfare between the FARC and government forces left civilian casualties everywhere.

Castañera moved to Argentina and lived there for two decades, until the peace accords allowed him to finally return. He told TNH that on returning he found a community still fighting hard to thrive and now free from the terror of its past.

“This region used to be very violent, full of coca,” he said, driving an old Toyota Land Cruiser down the dirt highway. Pointing to passing rows of young mandarin orange trees, he added: “So, this is all very beautiful to see.”

db/ag