When Claudia Cova’s 13-year-old son was diagnosed with cancer in April, her country’s ailing healthcare system couldn’t provide the drugs her son needed. Instead, she turned to tiny medical foundations that have emerged as a meagre stop-gap in the middle of Venezuela’s economic collapse.

Stark evidence of the humanitarian crisis swirling within Venezuela’s borders can be found in the country’s medical system: severe drugs and equipment shortages, hospitals and clinics in disrepair, people dying needlessly because they can’t find or afford medicine. The government, however, maintains that a crisis does not exist within the country.

Desperate families, and even medical staff, are relying on dozens of micro-NGOs to source the drugs and supplies now missing from Venezuela’s health centres: everything from oncology medicines to insulin and even baby formula.

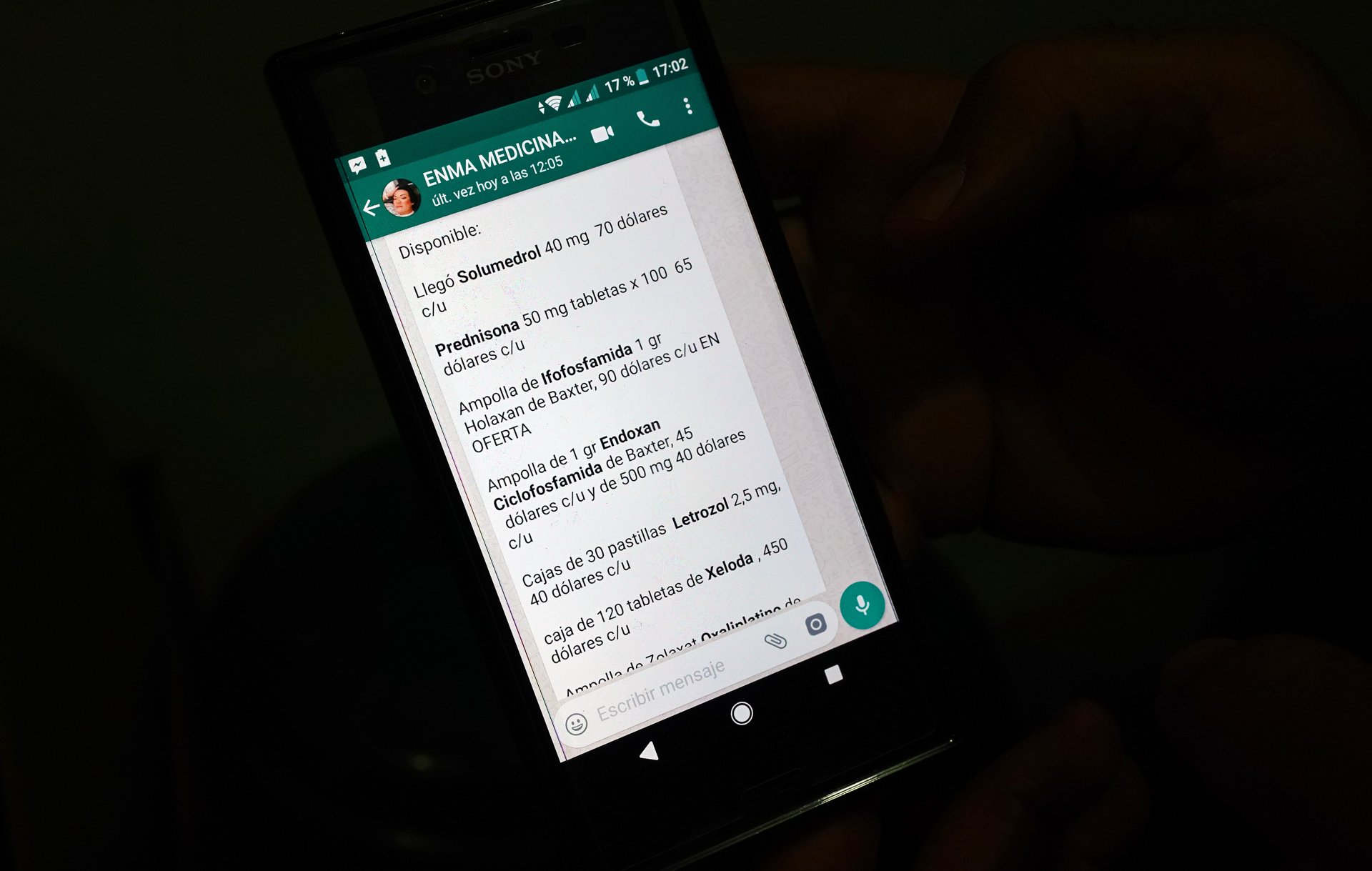

An online black market has also sprung up through social media networks, catering to desperate people like Cova, all searching for the drugs the state can no longer provide.

It’s a sign of a larger health crisis in Venezuela, where plummeting oil prices and fiscal mismanagement have left the economy on its knees and the country unable to import what it needs. More than 1.6 million Venezuelans have fled the country since 2015, sparking a humanitarian emergency throughout the region. Aid group Caritas says the average Venezuelan has lost more than 10 kilograms in the last year because they’re unable to buy enough food. Rates of infant and maternal deaths are rising after years of decline, according to UN estimates. British medical journal The Lancet says diseases like diphtheria and malaria are making a comeback.

With hospital medicine cabinets bare, Cova turned to the newer micro-NGOs and the social media black markets as the life of her son, Gabriel, hung in the balance. Piece by piece, dose by dose, Cova searched for the medicine she needed to begin treatment.

But time was running out.

“I had no idea about the magnitude of the problem until that moment”

On paper, Gabriel’s prognosis was good. He was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, a type of cancer that strikes the white blood cells. Doctors said he could expect to be cured with a treatment requiring eight different chemotherapy drugs administered over a six-cycle course: 48 doses in total.

But by the time the cancer was diagnosed, drugs shortages had reached alarming levels. Cova quickly discovered that the drugs Gabriel needed were not available in the state pharmacies obliged by law to provide medicine free of charge. More than eight out of 10 public hospitals are missing essential medicine that should be widely available, according to a March survey by Venezuela’s opposition-led National Assembly and an NGO, Médicos por la Salud.

“I had no idea about the magnitude of the problem until that moment," Cova says.

That’s when she approached Fundación Kenneth, one of the crop of tiny organisations that have emerged during the crisis. These micro-NGOs are often no more than one or two-person organisations, working out of living rooms and cramped back offices, founded and run by people who have lived through their own trauma of medical deprivation.

“That is gold. That is priceless. That doesn't exist in Venezuela”

Alfonso Brandt, 52, runs Fundación Kenneth from his small shop selling insect repellent in a Caracas mall. It’s named after Brandt’s son, who died of osteosarcoma, a type of bone cancer, in April 2016 at the age of 15. He started the organisation to honour Kenneth’s wish to help other children with cancer.

Brandt rummages through a plastic bag of medicine sent to him from the United States by the family of a patient who died. He extracts four small boxes and holds them up victoriously.

“That is oncological medicine," he says excitedly. “That is gold. That is priceless. That doesn't exist in Venezuela.”

Brandt gets most of his stock this way – donated and shipped to Venezuela by families of people who have died. In Venezuela, medicine and drugs have replaced organs as the “gift of life” of the recently deceased.

Despite Brandt’s enthusiasm, this latest gift is not even enough for a single treatment cycle, let alone a full course. Partial cancer treatments can be counterproductive, potentially stimulating – rather than quelling – the disease.

Brandt knows two people in desperate need of this particular drug. He says he will let doctors decide who will get them.

He holds up a photo of his son on his mobile phone. It shows Kenneth playing football: his outstretched leg is clear off the ground, foot poised to make contact with an approaching ball. He’s using crutches for support – his other leg has been amputated at the upper thigh.

Kenneth died because of his illness – not from the lack of treatment that is claiming lives today. Even two years ago, Brandt says, finding medication wasn’t a problem in Venezuela. He remembers picking up 50 bottles of chemotherapy treatment every three weeks from the state-run pharmacy.

“When we started the foundation helping children with cancer, we could find things. We could find oncological medicines,” Brandt says. “Now? Never. Now it is just not possible in Venezuela.”

Brandt removes the baseball cap he is wearing and points at the image printed on it: an embroidered rendition of the photo from his phone.

“Now, there’s no anesthesia, no plastic tubes for IVs, nothing,” he says, his voice tinged with rage. “And it is just getting worse and worse.”

He says he’ll only have oncological medicine for less than 10 percent of the people who come to him for help; he estimates the families of 4,000 people, most of them children seeking cancer treatment, will contact him this year.

“It’s impossible not to feel the weight”

When Cova sought out Fundación Kenneth in April, she was fortunate: Brandt gave her one blister pack – enough for one part of Gabriel’s first treatment.

To her, though, it didn’t feel like luck. She still needed six other drugs to start Gabriel’s treatment.

Her panic growing, Cova turned to the maze of social media marketplaces that have surfaced amid Venezuela’s medical shortages.

Many of the micro-NGOs devoted to sourcing medicine have tens of thousands of followers on social media. Their vast online reach combines with closed Facebook and WhatsApp groups boasting thousands of members, all trading vital information in a vast web of heart-rending pleas.

Members pass on news of pharmacies in neighbouring Colombia, or rumours of a rare delivery arriving at state pharmacies, or referrals to local medical foundations that may have a shipment of precious medicine.

Each of the 48 drug doses Gabriel needed for his complete treatment had to be sourced one by one. Every day, Claudia scoured the internet, Twitter, WhatsApp and Facebook groups, social networks, and the small medical foundations.

“It’s a full-time task: every day on social networks, the internet; every day asking people to find the medicines for the next cycle,” she says. “It’s exhausting.”

Black marketeers, too, haunt the web. They present a challenge to the micro-NGOs on the lookout for resellers posing as patients, but they also offer hope to people who can raise enough cash to buy the drugs they can’t get elsewhere.

Over several months, Cova was able to painstakingly piece together – and pay for – the drugs her son needed to begin his treatment, depleting her savings and raising funds from family and friends to buy on the black market. She estimates she spent more than $20,000.

As prices soar, she knows many others aren’t so lucky:

“I saw the situations of children in similar positions: parents looking for medications, or people looking for their mum, their aunt, their sister,” she says. “They were all in the same situation and it’s impossible not to feel the weight of that.”

“Patients aren’t dying because of the disease”

The government has continually refused to call the country’s overall situation a humanitarian crisis, and has repeatedly rejected international aid.

Yet the true extent of Venezuela’s healthcare crisis is laid bare in its major medical facilities, such as the University Hospital in the western city of Maracaibo, near the Colombian border. It was once one of the country’s finest, but is now barely functional. Thick layers of scum coat every surface. There is no water and there are frequent prolonged electricity outages. Bacteria contaminates incubators and operating theatres. Discarded beds and equipment are piled up in the corridors.

Dr Dora Colmenares, a surgeon who has worked at the hospital for 30 years, strides down a stained hallway, rattling off numbers: 600 – the number of essential medicines that are routinely available in wealthy countries; 300 to 400 – what citizens can expect in some other nations.

“In whichever country, even where there is war, there should be a minimum of 150 essential medicines available,” she says, pausing in front of a bare-shelved cabinet. “But in Venezuela, here there are fewer than 150 essential medicines, meaning that we are worse off than a war zone.”

Groups like Human Rights Watch have documented similar conditions and shortages across the country. The government rarely publishes basic health statistics, but the information it has released tells an alarming story. The last published health ministry report in 2016 showed a 65 percent increase in maternal mortality and a 30 percent rise in infant mortality, according to The Lancet.

“Patients aren’t dying because of disease," Colmenares says, “but because of the lack of medicines.”

Patients aren’t the only ones seeking help from micro-NGOs like Fundación Kenneth. Doctors and nurses in the country’s barren health clinics also ask the foundations to source drugs and supplies for their own patients.

“The job those foundations are doing here is so important,” says Dr Rafael Piroza, who runs a health clinic in Cumana, a city in Venezuela’s east. “They alone are helping us with food, medicine, machines, equipment, and with the elderly.”

“I told them they were murderers for letting people die”

A seven-hour drive east of Caracas in the city of Cariaco, Antonia Martinez Lozada has been fighting metastatic lung cancer for four years.

She sits outside her home in the fading light of a balmy evening. That morning, she had phoned “800-Salud” – the number for the national health authority mandated to provide treatment for cancer and heart disease – to give them a piece of her mind.

“Murderers! I called and told them they were murderers for letting people die,” Martinez bellows.

In 2014, when the 56-year-old education professor was first diagnosed, the country’s economy had already begun its plummet, and health services were in swift decline. The cancer had spread to her bones and organs.

Like Cova, Martinez turned to the micro-NGOs for help. At first, they gave her the life-saving drugs she needed.

But it didn’t last.

As the drugs supply shrank, Martinez’s life-line was cut. Today, she has spent more than a year without steady treatment, much to her doctor’s dismay.

“He said that one day without taking my medication is a day lost against fighting the illness," she says.

She has been forced to look elsewhere – anywhere and everywhere – to supplement the dwindling help from local aid organisations: Colombian pharmacies; social media contacts; the black market.

Her illness has drained her savings and emptied her three-bedroom home.

“I had to sell everything to get medicine – even my graduation ring," she says. “We had to sell the fridge, the A/C, and all the furniture because life is more valuable than furniture.”

She has nothing more to sell.

“We even sold the cheese slicer,” she adds, chuckling darkly.

“It might be a grain in the sea”

As needs rise, the space to find medicine is shrinking. The internet is a crucial tool for many, but a growing electricity crisis is taking its toll. Waves of unpredictable outages across the country often bring online activity to an abrupt halt – sometimes for days. During this time, no one can search, donate, or make transactions. And the crucial social media groups that helped people like Claudia Cova have been closing one by one in recent weeks. No one knows why.

The tiny medical organisations are finding it even harder to source medication. Many have closed. Those still in business say they’re watching their people die in unprecedented numbers.

Vanessa Ramos set up the two-person Fundación Jesed in Cumana last June. Her first donation consisted of the unused drugs of a friend’s child who had died of leukemia.

“I have had 16 cases recently where the patients die while I am looking for medicine – 16,” says Ramos, shaking her head with frustration. “And many times, you see children go into the hospital for one illness, get another infection in the hospital, and then die as there are no antibiotics.”

Despite the pervasive pessimism, Fundación Kenneth’s Brandt is determined to press on with his work.

“This is a gigantic situation that cannot be handled by a medicine foundation like ours,” he says. “But I think it is very important. It might be a grain in the sea, it might be a band-aid, it might be not enough, but I think every little thing helps, and the sum, the adding of each and every foundation, it is important.”

“When you know it is curable, the fact that you have to search for the medicine becomes even harder to tolerate.”

Cova and her son Gabriel are a bright spot in this bleak picture. Gabriel finished his treatment a few weeks ago.

The mother and son share a small, sunny apartment in the centre of Caracas. A lanky teenager wearing a knitted hat, Gabriel smiles sweetly in greeting, before sloping off for the refuge of his room.

Cova says her son’s diagnosis in April was devastating. But the hunt to find the missing drugs felt even more unjust.

“When you get to know the illness and know it is curable, the fact that you have to search for the medicine becomes even harder to tolerate,” she says.

In late September, the family received good news. A scan taken after Gabriel’s final chemotherapy treatment came through: he was declared disease-free.

For others, the future is less clear. Antonia Martinez Lozada, who hasn’t had steady treatment for her lung cancer in a year, is still searching for the drugs she hopes will keep her alive.

(TOP PHOTO: Shelves sit empty at a pharmacy in Maracaibo. A shortage of foreign currency means the government hasn’t been able to import enough food, equipment, and medicine.)

ss/il/am/js