As needs rise and the humanitarian sector looks to innovative ways of supporting people living through crises, could some of the answers lie in the power of AI?

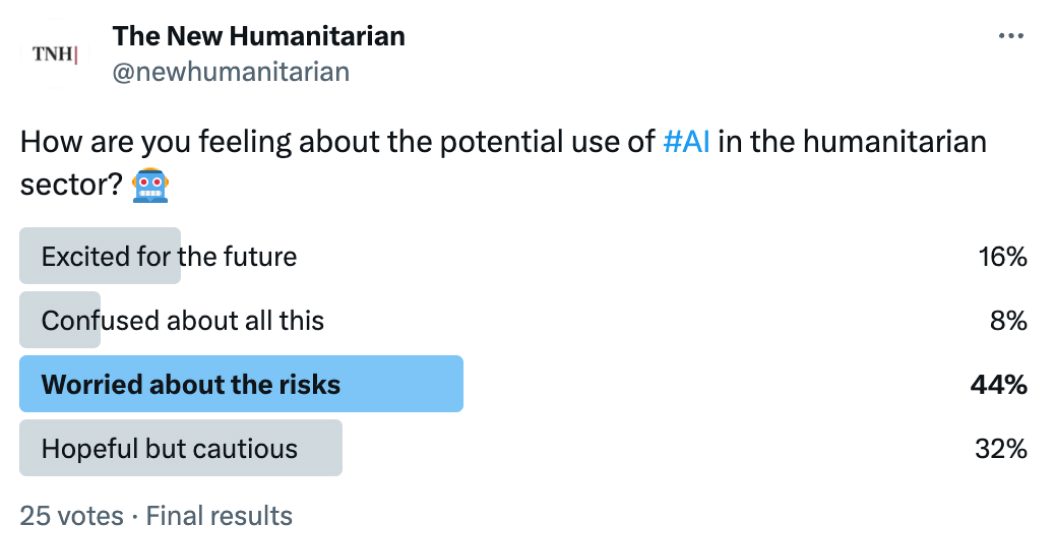

Possibly. Humanitarians are hopeful about what a future with AI might look like but concerned about the risks accompanying use of the technology, according to an audience poll at a recent TNH Twitter Space event – AI and the humanitarian sector: hype or hope?

AI – artificial intelligence, which we at The New Humanitarian prefer to think of internally as “non-human intelligence” – is already at work in humanitarian efforts. Speakers noted projects that included chatbots that help migrants find reliable information around their journeys, and a tool that produces sentiment analysis by sifting through media reports.

“We need to make sure that AI is not a gatekeeper, for example, for access to services”

They also pointed to concerns, including bias in the data used by AI tools, the ongoing issue of consent to collect and use data, and questions around access and exclusion.

“We need to make sure that AI is not a gatekeeper, for example, for access to services,” noted Purvi Patel, who has worked with the UN’s refugee agency, UNHCR.

Below are takeaways from the conversation, which featured a mix of speakers, some with extensive experience in AI and applying it to humanitarian work; others who were just eager to learn. They, and more than 500 participants from around the world, were eager to brainstorm about the hype, the hope, and the future around AI and its potential to impact humanitarian work.

You can listen to the event here:

Speakers

- Ximena Contla, an independent consultant on humanitarian assistance and project management focused on data analytics, humanitarian AI, and information management in complex crises. @XimenaContla

- Nat Gyenes, Digital Health Lab founding director from Meedan, a software company that has been supporting the development of AI-assisted chatbots to deliver critical information to earthquake victims in Syria and Türkiye. @GyenesNat @meedan

- Morgan Hargrave, manager of global programs at Namati, a grassroots justice network. @morganhargrave

- Karin Maasel, executive director of Data Friendly Space, a non-profit organisation committed to improving humanitarian response through better data, particularly in Natural Language Processing (NLP), a subfield of artificial intelligence. @KarinMaasel @DFS_org

- Purvi Patel, previously worked for UNHCR, currently an International Career Advancement Program (ICAP) and Aspen fellow in international affairs. @patelpurvip

- Brent Phillips, project manager and organiser of Humanitarian AI, an open source meetup community. He is also producer of the community’s podcast series Humanitarian AI Today. @brentophillips @HumanitarianAI

- Jacek Siadkowski, chief executive officer of Tech To The Rescue, a platform that matches tech companies with nonprofits to create solutions for social good. @siadkowski @TechToTheRescue

- Sarah W. Spencer, a consultant and researcher specialising in technology, foreign policy, and aid who focuses on the intersection of conflict and AI. @SSpencer2297

- Balthasar Staehelin, special envoy on foresight and techplomacy, International Committee of the Red Cross. @StaehelinB @ICRC

- Lauren Woodman, chief executive officer of DataKind, a global nonprofit harnessing the power of data science and AI in the service of humanity. @llwoodman @DataKind

AI: A beginner’s guide

Defining AI

While there is no universally accepted definition of artificial intelligence (AI), the term is often used to describe a machine or system that performs tasks that would ordinarily require human (or other biological) brainpower to accomplish, such as making sense of spoken language, learning behaviours, or solving problems.There are a wide range of such systems, but broadly speaking they consist of computers running algorithms (a set of rules or a ‘recipe’ for a computer to follow), often drawing on a range of datasets. Machine learning (ML) uses a range of methods to train computers to learn from existing data, where ‘learning’ amounts to making generalisations about existing data, detecting patterns or structures, and making predictions for new data. Experts offer conflicting views about the relationship between AI and ML.

AI and the humanitarian sector

AI presents a range of opportunities and benefits in the humanitarian sphere, from early warning and crisis preparedness to assessments and monitoring, from service delivery and support to operational and organisational efficiency.

Two main ways AI could support the humanitarian system are:

- offering new insights by collecting more information and identifying latent patterns in large, complex datasets otherwise unidentifiable to humans; and

- increasing efficiencies through automation

Source: Humanitarian AI: The hype, the hope and the future, by Sarah W. Spencer

What is NLP?

Natural language processing (NLP) enables computers to read a text, hear and interpret speech, gauge sentiment, and prioritise and connect to appropriate subjects and resources. The most familiar application is an automated call centre that sorts calls by category and directs the caller to recorded responses. NLP has become more widespread with voice assistants like Siri and Alexa. NLP uses ML to improve these voice assistants and deliver personalisation at scale.

Source: GSMA

‘Create algorithms and models that will help anticipate trends’: On the impact of AI on humanitarian work

When Sarah W. Spencer, consultant and contributor to The New Humanitarian, was doing research for her paper on AI and the humanitarian sector in 2021, she came up against a “deafening silence” on the topic. Two years later, with the release of ChatGPT and other AI tools that are “incredibly accessible… and are pretty cheap“, she says everything has changed.

“Recognising and, frankly, embracing and leaning into the fact that those questions [around AI] are becoming more difficult – and we have to keep up with them – is really important if we're going to be able to both protect against the harms, and realise the benefits of technologies in the humanitarian space.”

But even with this sudden spike in interest among the general public, there is relatively little awareness about potential use cases and implications of AI for the humanitarian sector and people living through crises, she noted.

Spencer believes that is due to a lack of genuine dialogue that goes beyond cost-benefits and risk assessments.

Lauren Woodman, Chief Executive Officer of DataKind, agrees.

“Recognising and, frankly, embracing and leaning into the fact that those questions [around AI] are becoming more difficult – and we have to keep up with them – is really important if we're going to be able to both protect against the harms, and realise the benefits of technologies in the humanitarian space.”

So, where should humanitarians start? Balthasar Staehelin, special envoy, Foresight and Techplomacy with the International Committee of the Red Cross, said humanitarians should be asking: “How are we, as humanitarians, cognizant about threats and trying to respond to those? How do we then use technology in order to enhance our operations, and our impact?”

Woodman encouraged technology literacy as a tool to ensure awareness around how data science and AI can help the sector: “Part of the work that we do on a day-to-day basis is helping organisations think about the right tools and the right applications,” she said.

Already, humanitarian organisations are asking for support to develop models to help them query documents or the many narrative reports on platforms like ReliefWeb, pointed out Karin Maasel, executive director of the non-profit organisation Data Friendly Space (DFS).

DFS has partnered with organisations to do sentiment analysis based on media reports and also launched a tool to process vast amounts of information – from news, reports, announcements, and assessments – on who is doing what and where in Türkiye and Syria after the earthquakes earlier this year.

Patel shared that UNHCR developed chatbots to help migrants get reliable information about their journeys, like how far to the next shelter or where there might be resources or assistance along the way. Another chatbot implemented in Brazil was designed to support victims of gender-based violence, providing them with access to information and resources in real time.

What might the future look like if humanitarians embrace this technology?

“Imagine a world where we can coordinate on the ground more effectively… in the middle of a conflict, in the immediate aftermath of a disaster… when things can often change rapidly on the ground, knowing which organisations are operating in the affected space, knowing the services and assistance that they are providing,” said Woodman.

Patel put forward a vision of a more proactive approach to crisis response. “We are a very reactive sector: We wait for bad things to happen, so we can react to them,” she said. “But we have the capability to create algorithms and models that will help [us to] anticipate trends of displacement or population flows, so we can have people and resources there proactively. And to translate online, xenophobic rhetoric, and try to predict when that might translate to offline violence and properly respond.”

‘Humans are continuously part of this’: On using AI now

Nat Gyenes, from Meedan, has been working to understand how large language models can support effective humanitarian response. Meedan pioneered a public health project to improve online information ecosystems. With Help Desk, they had a global network of public health experts responding to questions about COVID-19 from journalists, fact-checkers, and community organisations. From there, they realised they could use machine learning to turn a direct response service into an algorithmic capacity to better respond to communities that had similar questions, at scale.

“AI is a tool that, if not used properly, can cause harm”

“We're putting a lot of attention and emphasis into making sure that humans are continuously a part of this,” Gyenes said. “I would implore folks to continue to consider this from an equity perspective: Which individuals, which languages, which communities, which needs are the ones being prioritised?” she added.

Jacek Siadkowski, chief executive officer of Tech To The Rescue, gave an example of community involvement from his experience. At the last Hack To The Rescue hackathon, a tool for refugees started to take shape. This project focused on how to use generative AI to empower refugees and people on the move to help them better understand how their destination countries work, and what they need to do when they get there.

Many countries publish guidelines and documents, but they are rarely available in multiple languages, or are too difficult to understand. Generative AI can help in this case.

Brent Phillips, podcaster and organiser of the open source meetup Humanitarian AI, has been working with groups in 15 cities where humanitarians and AI developers gather to discuss how AI could be used in the sector. He noted that large tech companies are eager to support the humanitarian sector, while relying on that same sector to feed them use cases and ways to help.

‘AI is a tool that, if not used properly, can cause harm’: On risks and bias

Morgan Hargrave, manager of global programs at Namati, questioned the role of these tech giants.

“What lines of communication are open between especially the big humanitarian actors, and the almost entirely private corporations who are developing these tools?” he asked.

Gyenes added that the humanitarian community is coming together to do the work, which means “not relying necessarily on large tech companies to be the ones to develop the only large language models we use, the only technical infrastructure we use.”

“How do we make sure that no community is left in the dark?” she asked.

Ximena Contla, an independent consultant on humanitarian issues and data analytics, also worked on the DFS project to implement ChatGPT into the earthquake response in Türkiye and Syria. That team had to respond to questions about bias in the information generated by their tool. Contla said in the Twitter Space that biases are not something “randomly generated”, but they’re a result of the source biases in the source data, and that this highlights the importance of corroborating information garnered from tools like these. Models can be trained to give answers, but not necessarily the right ones.

“Now, more than ever, especially talking about artificial intelligence, especially talking about all of these tools that we have in our hands, the idea of how to make sense of the information we have comes as a priority,” Contia said.

Each of us has a responsibility to question what the computer is telling us, she added.

Biases in data could affect people in conflict areas by reinforcing discrimination or undermining the reputation and credibility of humanitarians, who could be targeted by misinformation campaigns. Staehelin similarly warned that algorithmic biases could impact decisions around which populations need support.

“AI is fed by data, and the quality of this data, especially in conflict, in war zones, may not be good enough,” he said. “And, inherently, they have a lot of bias. We have to be super careful that these biases do not influence our internal operations.”

“Can we learn from how the internet, mobile technology, social media has changed the work that we do?” he asked. “Or is AI something completely different?”

“We have populations who by definition are very often in a situation of vulnerabilities where the way they become data subjects, their data being used, there may not always be much of a free choice,” Staehelin said. “The whole notion of consent is very relative in terms of how we operationally manage that data so that people and the way we use the data can be at ease with it and can and that we do so respectfully.”

Patel suggested that humanitarian actors should have a defined purpose for the collection and use of data to avoid excluding people in vulnerable positions.

“AI is a tool that, if not used properly, can cause harm,” she said. “We need to make sure that AI is not a gatekeeper, for example, for access to services.”

‘Dirty dishes’: On why AI can’t fix everything

Hargrave posed the question to participants: “How much can the humanitarian sector learn from previous examples of ‘game changing technology?’”.

“Can we learn from how the internet, mobile technology, social media has changed the work that we do?” he asked. “Or is AI something completely different?”

There’s still a gap between the urgency of using and understanding technology and the connection with the real needs on the ground, explained Maasel of Data Friendly Space. “This debate that we're having on humanitarian AI can't just be about technology,” she said. “And it also needs to be about the ability of organisations to manage that change and make sure that this technology, as it's embedded in organisations, doesn't isolate anybody.”

Maasel mentioned one of her favourite sayings to explain this gap: “Everybody wants to save the world, but nobody wants to help mom with the dishes.” Those “dirty dishes” are the well-known, pre-existing problems and underlying challenges faced by the humanitarian system. Deep-rooted issues like weak accountability to beneficiaries, lack of funding for local organisations, and failures to guarantee the safety of humanitarian workers will not be solved overnight by powerful AI.

“Every time there's a new capability that comes to the fore like AI today, we tend to get sidetracked by it,” she noted. “What humanitarians can relate to the best are these ‘dirty dishes’ of the humanitarian system.”

For further reading: An AI primer

Articles from The New Humanitarian:

- The New Humanitarian | Generative AI may be the next AK-47 by Sarah W. Spencer. Aid and Policy - Opinion

- Four ways ChatGPT could help level the humanitarian playing field by Aanjalie Roane. Solutions and innovations - Opinion

Recommended by speakers and audience members:

- Leveraging Domain Knowledge for Inclusive and Bias-aware Humanitarian Response Entry Classification

- The Golem in the age of artificial intelligence

- Humanitarian AI: The hype, the hope and the future by Sarah W. Spencer

- ICRC is part of a joint initiative to quantify patterns of violence in accordance with International Humanitarian Law (IHL). Balthasar Staehelin moderated a discussion about how AI can help to uncover those patterns in humanitarian crises.

- From the Data Friendly Space blog: A Tale of Human and Machine Collaboration: Using AI language models to support the Türkiye and Syria Response.

- Be sure to also read insights from the DataKind blog.

- If you’re interested in data protection challenges linked to AI and machine learning in the humanitarian sector, read ICRC's Handbook on data protection in humanitarian action.

- With support from Microsoft, AI for Humanitarian Action, DataKind and Save the Children created a data analytics platform to help other humanitarian organisations embrace frameworks and systems that demonstrate the value of data.

- Check out the Humanitarian AI podcast.

- If you want to learn more about the use of AI language models to support the Türkiye and Syria Response, you can read this article.

- A podcast from DFS discussing ChatGPT and the use of large language models to support Türkiye and Syria earthquake response.

- Recently, Nat Gyenes hosted a workshop on AI chatbots for crisis response at Media Party in Chicago.

- If you want to learn more about the hackathon by @TechToTheRescue, just click on the following link.

Additional resources:

- AI for refugee communities

- Local communities should be part of designing humanitarian AI | World Economic Forum

- Prototype tools for predicting resourcing needs and addressing misinformation during humanitarian crises

- How AI can actually be helpful in disaster response | MIT Technology Review

- Harnessing the potential of artificial intelligence for humanitarian action: Opportunities and risks by Ana Beduschi at International Review of the Red Cross.

- Harnessing the power of Artificial Intelligence to uncover patterns of violence by ICRC Humanitarian Law & Policy.

- Why Adopting AI in the Humanitarian Sector is Not a Choice Anymore? by Impact Leadership newsletter.

- Is AI taking over our work, or are we taking over AI by the H2H Network.