Last month, Ousseni Souffiani’s life was turned upside down. He had lived in a hillside shantytown on the island of Mayotte, but a torrential downpour swept his flimsy home away, killing his wife and four of his children who were sheltering inside.

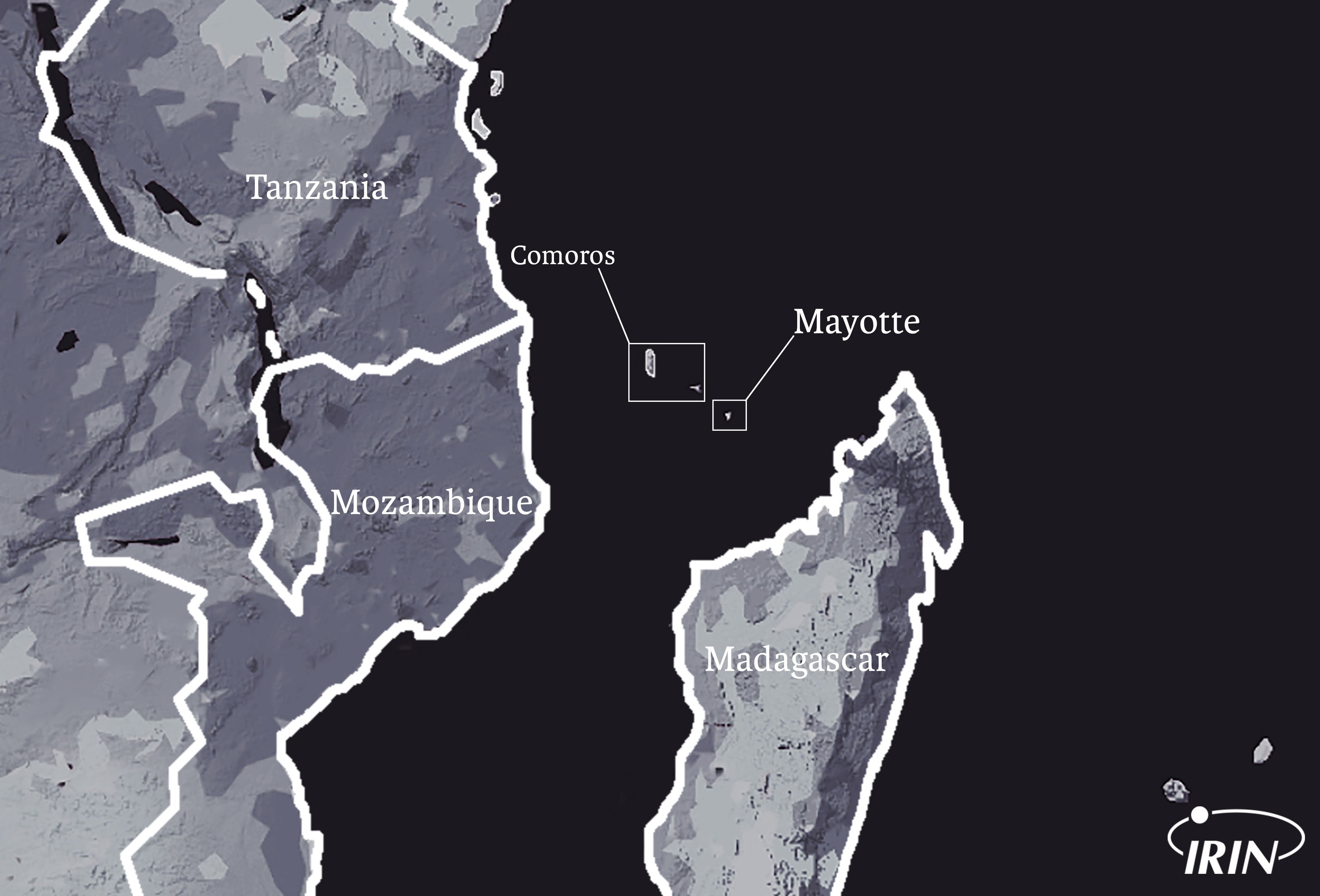

Like many other Comorian immigrants on Mayotte, a speck of French territory in the Indian Ocean, Souffiani’s home was a banga – made of corrugated sheet metal.

All that was left after the tragedy was an old foam mattress and a refrigerator, half-buried beneath the rubble.

When IRIN met Souffiani several weeks later, he was carrying an empty pot covered in cloth. He and his only surviving child, a six-year-old son, were going to a friend’s to ask for food. “We’re starting over at zero,” he said.

Souffiani had most recently worked as a labourer on a manioc field. But his life, like that of other undocumented migrants who’ve made the dangerous sea crossing from the Comoros – just 90 kilometres away – is a precarious one. They face discrimination, and are fearful of being caught by the government’s deportation machine.

Mayotte was once one of the four main islands in the Comoros, all under French control. But during the decolonisation period in the 1970s, it alone voted to join Paris rather than an independent Comoros, splitting the archipelago.

Despite its far-flung location and Comorian claims to the island, Mayotte has most of the trappings and advantages of an official French department – including membership of the EU.

A mirror image of the Mediterranean

So, just as migrants cross the Mediterranean Sea to reach Europe, Comorians cross a thin strip of the Mozambique Channel to reach Mayotte and the chance of a better life, usually on small kwassa kwassa fishing boats.

As in the Mediterranean, these boats are often in poor condition – they are frequently seized, so smugglers don’t use their best vessels – and they are overloaded.

About 7,000-10,000 Comorians – more than one percent of the islands’ population – died on the crossing between 1995 and 2012, according to a report from the French Senate. Many local observers cite higher figures, and the Comorian authorities claim it is “the world’s largest marine cemetery”.

French border patrols catch several kwassa kwassa per night. In most cases, the people on board are deported the very next day. Mayotte has a population of just over 200,000, and yet manages to deport about 20,000 people each year.

Mayotte is exempt from certain French immigration laws, and the border police do not always respect those that do exist. In a report last year, France’s human rights commission condemned the quick deportations in Mayotte, where most migrants don’t even see a lawyer or a judge before expulsion.

The commission wrote that seeking asylum in Mayotte was “mission impossible” and that this “worrying phenomenon” was unique in France. For Comorians, these difficulties are compounded by the fact that they believe themselves to be on their own land when they are on Mayotte.

Social tensions

The people of Mayotte and the Comoros have a common, if complicated, ethnic background, with ancestors arriving over the centuries from Africa, islands in the Pacific, Madagascar, and the Middle East. They also share a language and religion.

Most people on the islands speak some form of the main Comorian language, Shikomori, and adhere to the Shafi’i school of Sunni Islam.

Yet the long-settled Mahorans (people of Mayotte) resent the large presence of other Comorians on their island, which puts pressure on public services. Schools are now full of children from the other islands, and at Mayotte’s main hospital, most of the women giving birth are undocumented migrants.

Mansour Kamardine, one of Mayotte’s two representatives in the French parliament, considers the Comorian presence an “invasion” and regularly bemoans the grand remplacement of his island’s population. In 2016, he said Mayotte was on the verge of a “civil war”. In legislative elections last year, he easily won a seat in Paris.

Anti-migrant sentiment was also evident in the presidential election a few months earlier. Marine Le Pen, the leader of France’s far-right party, received significant support in Mayotte, even though most Mahoran voters are Muslim people of colour – not Le Pen’s normal supporters (only about one percent of Mayotte’s population comes from metropole France).

Le Pen has won popularity here by decrying the influx of migrants and criticising the Comoros. She recently expressed exasperation that the Comoros has the gall to “question the integrity of French territory”.

Some Mahorans refer to all other Comorians, no matter which island they’re from, as mdzwani, a slur derived from the name of the closest Comorian island. In 2016, a series of violent evictions by anti-migrant mobs left Comorians camped out in city squares.

In an online manifesto, one local group claims migrants insult, rape, rob, plunder, and burglarise the people of Mayotte, and disfigure the landscape with their banga huts.

But not all Mahoran agree with this depiction of Comorians. Ambidi Said Mattoir, a Mahoran activist who believes his island should still be part of the Comoros, says that many who speak out against immigration are hypocrites who employ undocumented Comorians in their homes and their fields. Without the labour these migrants provide, the economy might collapse, he told IRIN.

The “Dreamers” of Mayotte

Like undocumented “Dreamers” in the United States, people who were brought to Mayotte at a young age often grow up to find themselves treated like foreigners.

Chakour Ali, a 20-year-old electrician, came to Mayotte with his mother on a kwassa kwassa when he was five. He hasn’t left since. His request for nationality has been pending for more than two years; he’s still awaiting a response.

In the meantime, he can’t work legally or continue his education. He’d like to study electrical engineering. He graduated from high school two years ago, but now that he’s an adult he’s at greater risk of deportation.

If he had papers that would let him come and go, Ali says he would visit his father on Grande Comore. But, having no memory of the island, he has no interest in living there. “I know nothing about the Comoros,” he told IRIN. “I wouldn’t know how to live there.”

Closing borders and opening up divisions

France helped create the tensions now visible among the Comorian population.

In the 1970s, the Comoros voted for independence, but France retroactively interpreted the vote island by island – a way of holding onto Mayotte, the one island that had voted against independence.

In splitting the Comoros, France violated a UN mandate and an agreement with the Comoros to respect existing boundaries during decolonisation. This led the UN to repeatedly condemn France’s occupation of Mayotte, including in a resolution from 1976, just after the split.

In 1995, France introduced a “Balladur” visa requirement for Comorians wishing to travel to Mayotte. The visa was expensive and required an invitation from a Mayotte resident, so most Comorians turned to the kwassa kwassa, and the death toll started to climb.

Billboards in the Comoros proclaim that “Mayotte is Comorian and always will be”, “Balladur visa = legalised genocide”, “[International] law is flouted in the Comoros”, and so on.

Over the decades, France upgraded Mayotte’s status, with the support of the Mahoran people, who consistently voted for closer ties to France. But some activists say the referendums were masquerades controlled by France and influenced by French propaganda.

In 2011, in order to fulfill a campaign promise by then-president Nicolas Sarkozy, France made Mayotte a full overseas department – a move that enraged Comorians. Last year, current French President Emmanuel Macron made an insensitive joke about the kwassa kwassa boats, causing another diplomatic row with the Comoros.

Yet in September, a new French policy seemed possible: Paris announced a “road map” to opening up travel restrictions between the Comoros and Mayotte so that people would stop risking their lives to make the treacherous journey.

However, many Mahoran protested the plan, seeing it as too soft on illegal immigration. The original road map has now been scrapped and the Balladur visa requirement remains in place, the Mayotte prefecture told IRIN in an email.

Nowhere to go

After the accident in which Souffiani lost his family, his entire shantytown was deemed unsafe. The local government forced everyone out of their banga. However, for most people, including Souffiani, emergency housing was provided for only three weeks (for documented residents, it was three months).

Several people in the community told IRIN they had nowhere to go; they just wanted to return to their banga. Though these huts seem makeshift in construction, many are hooked up to the electricity grid, and some families have televisions and refrigerators. Souffiani will have to rely on his friends until he can once again afford such amenities.

As a young man, he crossed to Mayotte and spent years saving money, then went back to the Comoros to start a business selling clothes. But customs fees, corruption, and political instability derailed his business – the Comoros has endured more than 20 coup d’états in the four decades since independence.

Souffiani and his family ended up on a kwassa kwassa back to Mayotte so the children could receive a good education. That education is what he still wants for his six-year-old boy. “His future is what’s on my mind,” he explained simply.

ec/oa/ag