In Nigeria’s northeast, the jihadist group Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) is Islamic State-central's most successful regional affiliate, combining a ruthless insurgency with an elaborate governance and tax system that has enabled it to withstand sustained military pressure.

While modelled on the administrative system of ISIS-central, based in Syria and Iraq, ISWAP has adapted the framework to the Lake Chad Basin. At the heart of its governance model is a network of formal departments known as dawawin – essentially ministries – tasked with overseeing military operations, taxation, religious enforcement, justice, and public welfare.

These institutions provide the operational foundation through which ISWAP seeks to project itself as an alternative authority to the Nigerian government in the territory it controls.

This investigation explores the system of rule and revenue streams that ISWAP has built in what it refers to as the dawla – the so-called caliphate it has established in parts of northeastern Nigeria and the Lake Chad region. The report is based on in-depth interviews with fishers and traders that regularly visit ISWAP territory on a string of islands in Lake Chad, as well as former ISWAP officials and clerics who have left the group and quietly resettled in northern Nigeria.

Understanding ISWAP’s governance structure is key to explaining how the group sustains itself, extracts resources, and maintains its influence – offering an insight into the political economy of extremist insurgencies and their ability to fight on.

Unlike modern state systems, ISWAP’s governance is not built on codified legislative processes. Its legal and administrative authority is rooted in its interpretation of sharia law, enforced through religious courts and morality police – known as hisbah – while executive control is exercised by the dawawin.

Its governing Shura Council (Majlis al-Shura) operates primarily as a consultative body, providing strategic oversight, approving leadership appointments, and ensuring doctrinal conformity. This layered administrative system – although adapted from ISIS-central – reflects ISWAP’s effort to combine jihadist insurgency with a quasi-state apparatus, embedding itself within the civilian life of communities under its influence.

How does ISWAP win hearts and minds?

ISWAP understands the governance issues communities face when they come into contact with the Nigerian state – the corruption, the casual violence and impunity. Right from the split from so-called Boko Haram and its leader Abubakar Shekau in 2016, ISWAP has understood that winning the hearts and minds of civilians under its control was key to its entrenchment and furtherance of its jihadist agenda.

Over the years, the group has presented itself as an alternative to the state by filling the administrative gaps left by the authorities, particularly in remote areas. By carrying out governance activities, ISWAP demonstrates how jihadist organisations attempt to legitimise themselves before the people, making it easier to recruit and generate revenue, while simultaneously making it harder for the government to uproot them.

In the case of ISWAP, many of the services it provides are free, including the provision of potable water – usually through the construction of boreholes – and generators to pump the water.

The group also provides boats and canoes for riverine communities that need them, especially those who have to cross rivers to access their farmlands.

In the area of healthcare, civilians affected by military bombardments or general sickness are treated free of charge at ISWAP-run medical facilities. Where drugs are unavailable, patients are provided with prescriptions to purchase them elsewhere, often from drugstores within ISWAP territory.

ISWAP also responds to the needs of communities by constructing latrines, providing protection against crimes – such as armed robbery and livestock rustling – installing grain-grinding machines, and settling disputes through religious courts.

These courts handle cases between farmers and herders, marital disputes, and conflicts between fighters and civilians. Interest-free loans are provided to traders, especially those affected by military attacks or those considered supportive of ISWAP’s cause. If these borrowers suffer losses – from airstrikes or accidental fires – the loans are written off.

Additionally, agricultural inputs like seeds and pesticides are also distributed free of charge, although farmers are restricted from selling their produce outside ISWAP territories. The group purchases the produce to maintain food security within its controlled areas.

How rich is ISWAP?

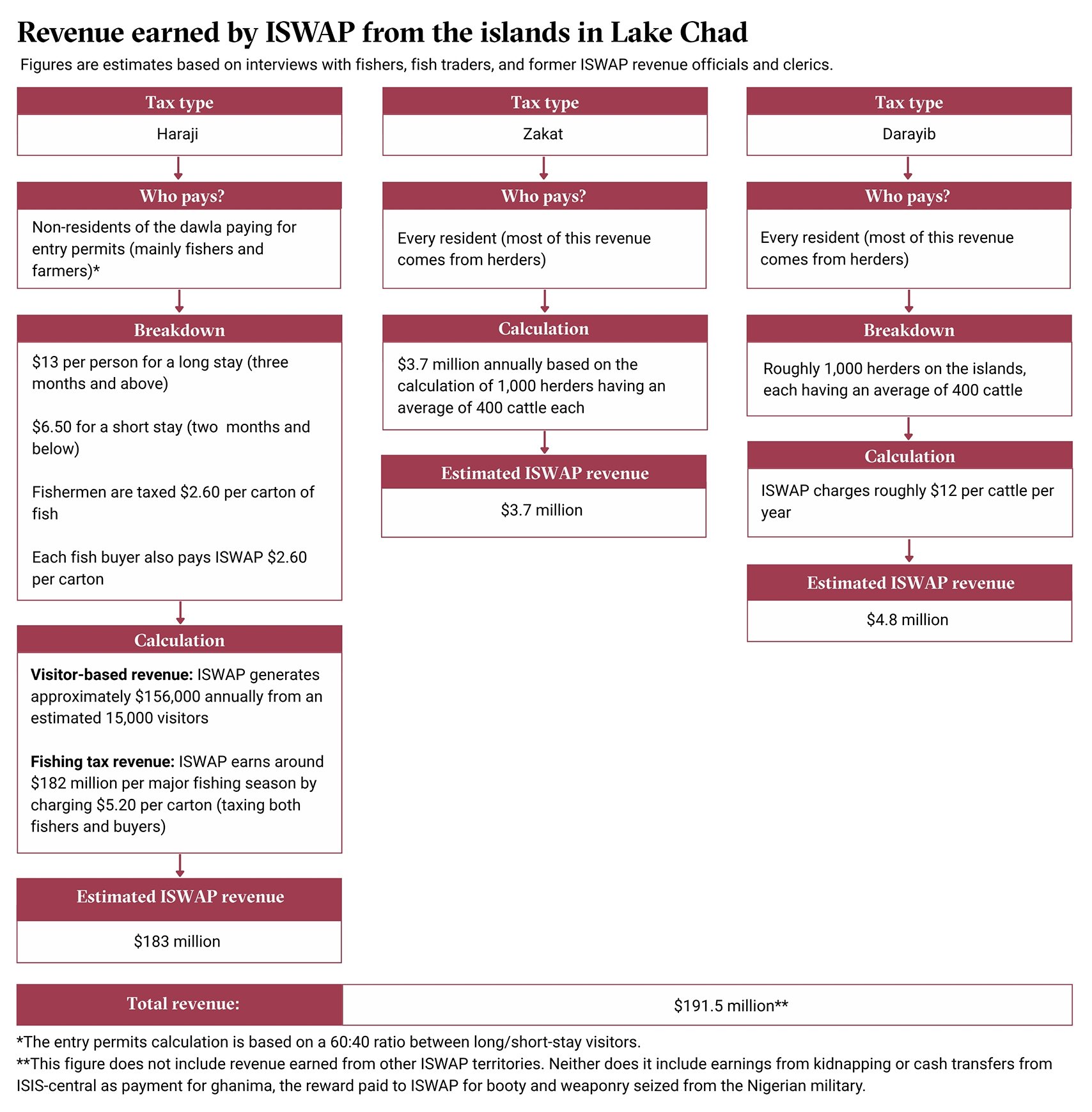

The New Humanitarian conservatively calculates ISWAP earns the equivalent of more than $191 million annually – largely from taxes levied on fishers and livestock owners using the islands.

That does not include revenue from other areas in Nigeria where it has a presence, earnings from kidnapping, or the reward payments made by ISIS-central for equipment it captures from the Nigerian military – known as ghanima, or spoils of war.

To put this revenue haul into perspective, Nigeria’s northeastern Borno State government collected the equivalent of just $18.4 million in taxes in 2024.

ISWAP administers three broad categories of taxation: zakat, haraji and darayib. Each tax has a separate receipt that is issued after payment.

ISWAP collects zakat from cattle-owning farmers worth roughly $3.7 million a year. The tax ranges from 3.3% to 1%, depending on herd size – the lowest rate levied on herds of more than 60 to 80 animals.

ISWAP does not physically take the cattle but instead collects the cash equivalent – based on a pre-determined market value, eliminating the possibility of herders undervaluing their livestock.

It also imposes a similar tax structure on sheep and goats but does collect the animals, reportedly for festive occasions and other internal uses within the group.

Haraji refers to the payments made by non-residents who enter ISWAP-controlled territories temporarily for livelihood purposes. It encompasses both the entry permit fees required to access these territories and the taxes levied on the economic activities conducted within them, amounting to around $183 million each year.

Haraji is primarily paid by fishers, fish dealers, and farmers – with the fishing sector generating the bulk of the revenue. For ISWAP, haraji serves as a key source of income from the external visitors who benefit economically from the resources within its territory but do not permanently reside there.

Before entry into ISWAP’s territory, every individual is required to pay a $13 fee. Those with cash pay immediately at the first checkpoint before being allowed to proceed. Those without the money are permitted to enter after making a pledge to pay following their business activities.

In such cases, the group leader is held accountable for ensuring that all deferred payments are settled. Each person receives a permit or receipt, which serves as proof of payment and protects them from harassment by ISWAP’s inspection task force operating on the islands. With this permit, individuals are not disturbed.

Once inside, fishers are required to pay additional fees to be in allocated fishing areas. The amount depends on the size of the area requested and the fishing method they intend to use.

According to fishers interviewed by The New Humanitarian, these fees range from $13 to $196 and cover an entire fishing season, usually from February to June.

Before exiting the territory with their goods, each fisher or fish trader is charged a fishing tax of around $2.60 per 100 kilogram carton of fish. During a normal fishing season ISWAP can generate around $156,000 from entry permits alone.

According to multiple sources interviewed, haraji revenue fluctuates depending on the season and the overall security situation. Disruptions such as attacks by rival Boko Haram fighters, military operations, or temporary suspensions of fishing by ISWAP – often due to suspicions of fishers collaborating with the security forces – can significantly affect income.

The fishers association in the Lake Chad areas controlled by ISWAP has 15,000 members on its books – primarily from Nigeria, Niger, Chad, Cameroon, Burkina Faso, and Mali. Of this number, 10,000 are reportedly large-scale fishers who, during a peaceful fishing season, typically harvest between 2,000 and 5,000 cartons of fish. The remaining members are made up of small-scale fishers and labourers who work under the major operators.

According to an association official, the fishing tax per carton varies, but the average levy is around $2.60 per carton. Therefore, if each of the 10,000 major fishers harvests approximately 3,500 cartons per fishing season, the total amount paid in fishing taxes is around $91 million.

But ISWAP imposes a double-taxation as fish dealers are also expected to pay the $2.60 on the 35 million cartons that are harvested before they are transported off the islands, earning the group another $91 million.

Is there resistance to ISWAP taxation?

Darayib represents a more flexible and arbitrary form of taxation, often applied when additional funds are required beyond what zakat and haraji can provide. This is paid by everyone residing on the islands, including the ISWAP leadership. The amount levied is at the discretion of ISWAP, but can reach $4.8 million.

Unlike zakat and haraji, which have classical Islamic justifications, darayib has been a source of internal dissent. While zakat provides a predictable revenue stream, darayib gives ISWAP financial flexibility to fund major operations or urgent expenditures such as weapons procurement or medical supplies.

Clerics and former officials have faced a backlash for criticising ISWAP’s leadership over its repeated imposition of darayib – up to three times a year – in clear violation of guidance from ISIS-central.

Interviewees said most of the darayib revenue comes from herders because there are many of them on the islands, owning hundreds of thousands of cattle. According to these sources, ISWAP charges a flat rate of $12 per animal. There are reportedly at least 1,000 herders on the islands alone, from Gamboru Ngala to Tumbum Gini, with some herders having as many as 2,000 cattle, although 400 would be a rough average.

With no fixed rates or codified standards, the amounts imposed are left to the discretion of leaders, creating opportunities for abuse and corruption. This has led to tensions within ISWAP’s ranks, particularly between clerics – who feel religiously obliged to speak out – and commanders seeking to maximise revenue.

“This [darayib] was supposed to be a once-a-year levy on the people, only when there was a need,” a former ISWAP cleric, who was expelled by the group, told The New Humanitarian. “ISWAP has turned it into a recurring practice, collecting it annually and even multiple times within the same year.”

Asking not to be named for security reasons, he said that nine other clerics were chased out of the islands in 2024 for voicing a similar criticism of the darayib.

“The clerics brought the attention of the leadership to what they saw as an error in the interpretation and administration of darayib,” he noted. “It is only supposed to be collected during periods of cash shortages, and not more than once a year, regardless of the need or emergency.”

Another former senior cleric recounted a meeting – prior to the expulsions – in which ISWAP leader Abu Musab al-Barnawi allegedly acknowledged the tax collection contradicted guidance by ISIS-central.

Nevertheless, according to the cleric, al-Barnawi tried to justify the measure. “The Islamic State in Iraq and Sham [Syria] doesn’t understand the realities we face here in West Africa,” he reportedly said. “Their recommendation to collect darayib only once a year reflects their own political context and what works for them.”

Al-Barnawi regarded it as a matter of survival and was willing to defy ISIS-central on that point.

“‘If we limit collection to once a year, we risk not having enough funds to supply our soldiers with medicines, fuel and other essentials needed to sustain the war’,” the cleric remembered him saying. “‘Disobeying ISIS on this matter and remaining strong is better than obeying and losing everything’.”

How extensive is ISWAP’s influence?

Most economic activities supporting ISWAP are run by civilians. But all business activities are regulated by the group. Traders need ISWAP’s permission to bring goods into its territories. Even fighters engaging in trade during their spare time must obtain clearance to purchase goods outside the controlled areas.

Goods often come from neighbouring Niger, but also from other parts of Nigeria, including Kano, Kaduna, and Lagos. ISWAP uses trusted intermediaries to source essential items like spare parts and medical supplies, offering premium prices to encourage external traders to work with them despite the risks.

In terms of governance, former members of the group, including those in positions of authority, said ISWAP’s territorial administration is largely confined to Nigeria, particularly Borno State.

Its Lake Chad Basin dawla is based within Nigerian territory, though its operational activities span across borders. Attacks in Cameroon and Niger are part of ISWAP’s regional jihadist campaign, but civilians in those areas are usually advised to relocate if they wish to live under ISWAP’s governance.

Neighbouring countries, however, are critical to ISWAP’s supply chain. Goods, fighters, and external support flow through Chad, Niger, and Cameroon. These corridors are essential for the arrival of foreign fighters and trainers, especially from Central and North Africa, linking ISWAP to broader transnational jihadist networks.

How difficult is life under ISWAP?

Life under ISWAP is fraught with contradictions. While basic services are provided, civilians have no say in how they are governed. Those who dare to question the group risk severe punishment, including imprisonment and death. The semblance of order and protection often masks systemic oppression, with the threat of violence hanging over the civilian population.

For many residents, compliance is less about ideological affinity and more about pragmatic survival, as ISWAP offers some protection from rival armed groups, bandits, and often abusive state security forces.

ISWAP’s governance strategy represents one of the greatest challenges to Nigerian state authority in the Lake Chad Basin. By embedding itself within local communities through service delivery, economic regulation, and religious legitimacy, ISWAP transforms from a mere militant group into a parallel governing authority.

Its ability to provide security, mediate disputes, and regulate local economies has allowed it to entrench itself deeply into the daily lives of civilians, fostering a degree of dependence that is difficult to dislodge through military operations alone.

The Nigerian government and its military allies – particularly the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) – have primarily responded through military operations, including airstrikes, raids, and ground offensives. While these efforts have degraded ISWAP’s fighting capacity in certain areas, they have failed to present a credible alternative form of governance to communities living under ISWAP control.

This failure allows ISWAP to maintain a degree of legitimacy and operate an economy that, while illicit, meets the basic needs of those it governs.

Moreover, ISWAP’s governance model, by offering order and protection from both criminal groups and predatory elements of the state, poses a long-term strategic threat. The combination of religious legitimacy, security provision, and economic integration makes ISWAP’s influence durable.

Displacing ISWAP, therefore, will require more than military victories: It will require the Nigerian state and its international partners to provide reliable security, a fair system of justice, functional services, and accountable local governance.

Without a shift in strategy to combine military efforts with governance and development initiatives, ISWAP’s political savvy will continue to make it a formidable actor in the Lake Chad Basin insurgency.

Edited by Obi Anyadike.