Lack of humanitarian access is fast becoming a defining issue in Ethiopia’s three-month conflict in Tigray: The UN and aid agencies say they’re not allowed to move sufficient personnel and goods into and around the region, and are being denied visas to bring in new international staff.

Aid workers, NGO managers, and others involved in the response told The New Humanitarian the rules on access keep changing, and agreements with the government have not delivered as hoped, leading to a state of paralysis in the relief effort.

In a statement today, Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed said: “Ending the suffering in Tigray and around the country is now my highest priority. This is why I am calling for the United Nations and international relief agencies to work with my government.”

But even the Ethiopian Red Cross, which enjoys relatively good access, said this week that it could only reach 20 percent of the people in need in the Tigray region.

The Red Cross, church-affiliated aid groups, and Ethiopian national aid workers have fewer hurdles, but foreign aid groups say they have barely got started. Veteran NGO leader Jan Egeland, secretary-general of the Norwegian Refugee Council, said: “I have rarely seen a humanitarian response so impeded and unable to deliver.”

Even for the few aid workers who do manage to become deployed in the region, “the ‘rules of the game’ change on a day-by-day basis”, according to a UN update shared with international NGOs at the end of January, and obtained by TNH.

Abiy’s government says its “law enforcement” operation to quash a revolt by the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), which began in early November, has largely succeeded, with rebel forces driven out of towns and cities, and dozens of rebel leaders killed or captured.

However, the UN and media reports say fighting with the TPLF and allied militia continues in mountainous rural areas. Rebels have mounted guerrilla attacks, hitting military convoys and checkpoints. The military picture is complicated by the presence of the Eritrean army – denied by both Asmara and Addis Ababa – as well as militia from Ethiopia’s neighbouring Amhara region.

Several aid officials familiar with the situation – all insisting on anonymity given the sensitivity of relationships with the government – said people in Tigray face mounting hardship as a result of three months of violence, looting, and the collapse of trade and public services.

Up to four million people – of a total population in the region of six million – will need some food aid in 2021, according to projections by specialist aid groups. Tens of thousands of people who have fled to Sudan, or to neighbouring Ethiopian regions, also require assistance.

UN estimates say at least 2.5 million people need relief aid right now in Tigray – one million were receiving allowances to stave off extreme poverty even before the crisis began. But NGOs and UN agencies are unable to reach rural areas to make assessments, which they say are the starting point of an effective response.

The Ethiopian government says it has already helped 1.8 million people, delivering 31,000 tonnes of food and other supplies last month, often alongside the national army – a basic food ration of 15 kilos per month for 2.5 million people would require 37,000 tonnes a month. However large the government’s aid operation, it seems to have had little effect on reports of widening desperation and destitution.

While Tigray has been largely cut off from the outside world – phone and internet services disconnected, electricity cut, roads blocked, and banks closed – the conflict has been marked by extensive looting and damage to public facilities, shelling of civilian areas, rights abuses, and ethnic targeting.

Reports indicate widespread killings of civilians and sexual violence, high levels of displacement, rising hunger, lack of access to healthcare, and little farming, commercial activity, or trade. Local government and law and order are also in disarray, according to the Ethiopian human rights commission. Independent media and human rights groups have had almost no ability to verify claims on all sides, or to independently assess the situation.

In response to an Economist article entitled “Wielding hunger as a weapon”, a senior Ethiopian official denied the charge but gave a clear signal of government intent: “In this complicated and high-stakes operation, humanitarian, diplomatic and media agencies will have to endure the inconvenience of heeding to the direction of the government.”

Three deals, little progress

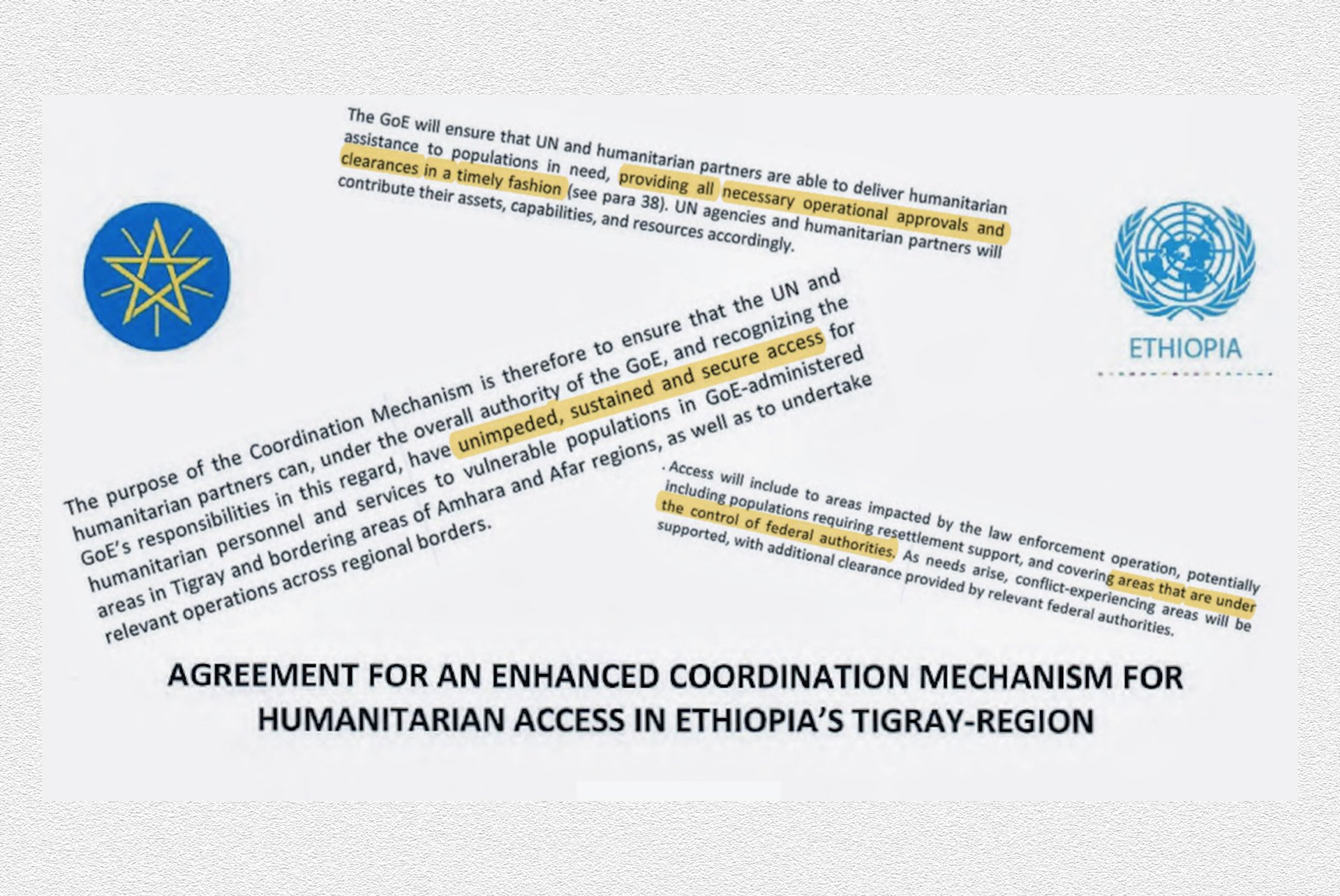

The UN, the US, the EU, and several other international organisations and human rights groups have repeatedly called for “unimpeded”, “unfettered”, or “unhindered” access for aid agencies to make assessments and deliver food and other humanitarian aid.

The UN has tried to negotiate response procedures, to little effect, and Ethiopia so far has brushed off diplomatic demands for unhindered access, leaving dozens of aid agencies at a near-standstill on the sidelines of an unfolding humanitarian disaster.

The first agreement, signed by the UN and the Ethiopian government on 29 November, proposed a series of mechanisms to process aid agency requests and coordinate operations. It had some success in clearing cargo requests, but is “ineffective for personnel clearances”, according to a 22 January update shared with NGOs by the UN’s emergency aid coordination body, OCHA.

OCHA’s Ethiopia spokesperson Saviano Abreu said some requests for staff deployment had gone more than a month without approval. Aid officials also told TNH that paperwork from the central government isn’t always respected by regional authorities, requiring renegotiation at the local level.

The UN also sought a second agreement – for 16 UN agencies and 25 NGOs to have a six-month blanket travel permission – but that too has not materialised. OCHA, in a 25 January diplomatic letter (also obtained by TNH) to its Ethiopian government counterpart, the National Disaster Risk Management Commission, or NDRMC – stressed that the UN and the aid agencies had proven track records working in the country. The letter also highlighted that $76 million had been raised from international donors to pay for the response. Abreu told TNH the request is “still pending”, describing the situation in Tigray as “extremely dire”, with “insecurity and bureaucratic obstacles” hampering the humanitarian response.

A third deal was contained in a joint announcement between the government and the UN World Food Programme (WFP). On 6 February, the UN’s food agency claimed a “breakthrough” as Ethiopian Minister of Peace Muferihat Kamil said aid worker travel and visa requests would be expedited – and communication capabilities for response operations improved – but he didn’t refer to the blanket travel permission sought by the UN.

As part of this agreement, the UN did secure approval to move 25 more staff to the region, although dozens more UN and NGO aid workers remain in the capital awaiting travel permits. WFP said it would scale up the supply of emergency food rations for up to one million people as well as provide logistics support. Kamil said humanitarian assistance should be “expanded and intensified without delay”.

Aside from the UN efforts, international NGOs say they are continuing to pursue access permission from the government’s Ministry of Peace directly. TNH has obtained a joint letter from NGOs, dated 1 December 2020, asking for permission to scale up. Aid officials said the international NGOs would prefer to stay separate from UN arrangements, but told TNH that verbal assurances from the NDRMC have not been formalised by its parent, the Ministry of Peace.

Aid officials acknowledged that over recent weeks a limited number of foreign aid workers are being allowed as far as the regional capital, Mekelle, but said even they were largely blocked from travelling out further into the region. One aid worker said expatriate aid workers were particularly relevant in the situation, so as to provide a buffer to official interference with Ethiopian staff. Another disagreed, saying the situation was so delicate that local knowledge was paramount.

A recent UN map shows most of the Tigray region to be “inaccessible” for aid operations. The term includes a range of possibilities: ongoing insecurity and fighting, government reluctance to allow outside visitors, or areas of possible rebel control.

Meanwhile, no discussions or agreements have been disclosed on how aid could reach any area controlled by the TPLF.

The government wants to prevent assistance from reaching the TPLF, keeping very tight control on aid flows as well as on valuable tools like satellite phones, NGO officials said.

Given the level of control the government seems to want to exert, they feared their work on the ground would struggle to maintain distance from the Ethiopian military, undermining their neutrality and independence, while the use of military escorts to accompany aid teams and convoys could make relief operations a rebel target.

The International Committee of the Red Cross and Médecins Sans Frontières enjoy better mobility and access than most. Nevertheless, in a blog, one MSF staffer wrote on 1 February: “We still haven’t been able to go to many places, because access is still difficult, either because of insecurity or because it is hard to obtain authorisation.”

bp/ag