UN aid to Syria’s rebel-held northwest will come to a halt this month if Russia does not agree to a deal in the Security Council, potentially putting healthcare, food, and rudimentary shelter for millions of people in jeopardy.

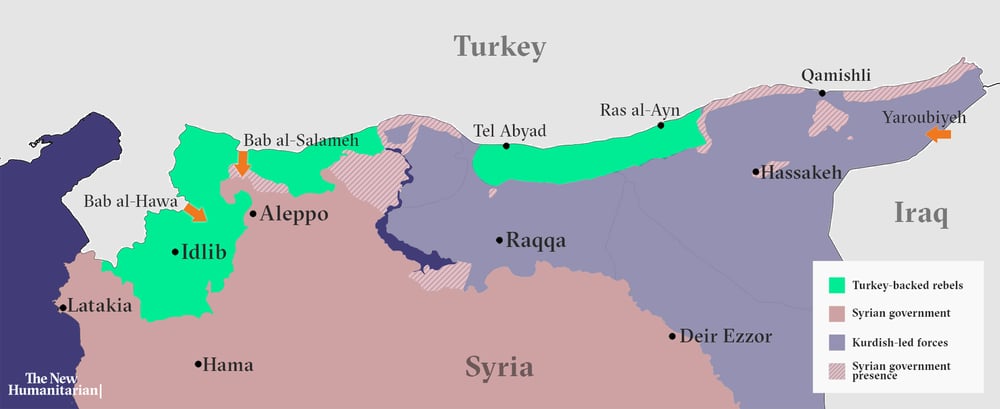

After more than nine years of war, the government of President Bashar al-Assad, backed by Russia and Iran, controls most of Syria, except Idlib province and surrounding parts of the northwest, and the mostly Kurdish-controlled northeast.

Damascus has a history of blocking aid within Syria to the northwest and other parts of the country it says are controlled by “terrorists.” The UN estimates that some four million people live in the Idlib province and other opposition-held parts of northwestern Syria. Seventy percent of them are in need of some sort of assistance, including many displaced people who were forced to flee a recent government offensive and are now facing rising rates of hunger.

That means that all aid to the northwest is trucked in from neighbouring Turkey, by both NGOs and the UN. UN agencies have been authorised to bring aid across Syria’s borders without al-Assad’s approval since 2014 by Security Council Resolution 2165 and its latest update, numbered 2504. The resolution allows the UN to use two Turkey-Syria border crossings, Bab al-Hawa and Bab al-Salameh.

The resolution is set to expire on 10 July, and major powers are still hashing out the details of a possible renewal, which was discussed in the Security Council on Monday. All eyes are on Moscow, as al-Assad’s ally could effectively end UN cross-border aid with a single veto.

The Kremlin has stepped in to slow down or stop UN aid before: In January, a Russian-Chinese veto ended UN use of a Syria-Iraq crossing, Yaroubiyeh, into the northeast, and allowed aid to the northwest to continue for only six months rather than a year. Russia and the al-Assad government argue that any aid needed should transit through government territory.

In a 14 May report, UN Secretary-General António Guterres asked the Security Council to renew UN use of Bab al-Hawa and Bab al-Salameh for a full year, a demand backed by aid organisations working in Syria and three of the Security Council's five veto-wielding members, who also seek the reopening of Yaroubiyeh. They say a renewal is especially key now, given the backdrop of a massive economic crisis in Syria, not to mention the global COVID-19 pandemic.

“On top of an already extremely difficult situation throughout the entire country, you have this economic collapse”, Kevin Kennedy, the UN’s regional humanitarian coordinator for Syria, told The New Humanitarian. “The price of food now, by our estimate, is up 200 percent since this time a year ago, in a country where people were already under economic strain.”

Rising hunger in Idlib

In late spring, Syria’s economy suddenly crumbled under the combined pressure of the cumulative effects of the long war, the coronavirus, a banking crisis in neighbouring Lebanon, and new US sanctions.

The number of food insecure Syrians has climbed from 7.9 million to 9.3 million in just six months, according to the World Food Programme (WFP). That likely includes many people in the northwest, where most of the UN’s cross-border aid goes. The Islamist-held Idlib area is under a tight blockade from Damascus, and it saw intense conflict in 2019 and early 2020, displacing nearly a million people and causing widespread damage to civilian services and infrastructure. An early March deal between Turkey and Russia put a government offensive to retake the region on hold.

Even before the recent economic breakdown, UN officials had begun to receive worrying reports of hunger in the northwest, with, for example, the share of acutely malnourished pregnant and lactating women rising from 5 percent to 40 percent in a year.

Since then, the situation has worsened. “In large part this is attributed to the increased food insecurity brought about by the economic downturn and the currency fluctuation”, said a UN official, who requested anonymity due to the sensitivity of the situation. “Obviously those effects are felt across the country, but it is safe to assume that those most vulnerable are first affected and worst affected.”

Even before the recent economic breakdown, UN officials had begun to receive worrying reports of hunger in the northwest.

The Bab al-Hawa crossing to Idlib accounts for three quarters of the 38,000 truckloads of aid that crossed the border with Security Council permission since 2014. (Other supplies are brought in by Turkish aid groups, including the Red Crescent, and NGOs outside of the UN umbrella.) Deliveries under the UN system have increased sharply in 2020, rising 75 percent since the end of last year.

If the Security Council fails to agree on an extension, starting on 11 July, WFP food trucks, UN assistance to displacement camps, and supplies for the World Health Organisation’s work against COVID-19 would all be blocked.

Even non-UN aid would be affected, since many NGOs depend on the UN’s aid coordination body, OCHA, for funding, planning, and logistics. Some groups may also be reluctant to engage in cross-border activities without the legitimising presence of the UN, not least because of the potential security, legal, and reputational risks that stem from operating in an area controlled by Tahrir al-Sham, a jihadi group under UN and US counterterrorism sanctions.

Stressing the gravity of the issue, Guterres informed the Security Council in May that it is “currently simply impossible” to reroute the aid through Damascus, an assessment echoed by OCHA chief Mark Lowcock in the Security Council on Monday.

The situation in the northeast

While Idlib and the rest of the northwest have a larger population in need than the mostly Kurdish northeast, aid groups say re-opening Yaroubiyeh, which the UN only used to truck in medical supplies, is particularly important given the spread of COVID-19.

Although the northeast has so far only registered six cases of COVID-19, one of which was fatal, there is concern about the spread of the virus in crowded displacement camps.

Aid workers who spoke to TNH in December, when Resolution 2054 was up for debate, were highly critical of Yaroubiyeh’s closure. They noted that al-Assad’s government had not previously allowed medical supplies to reach the northeast and that it is known to deliberately limit surgical and other supplies to areas it cannot control. Moscow defended its decision to close the crossing by saying aid could be brought to the northeast via Damascus, and then delivered across frontlines once within the country.

Six months after Yaroubiyeh’s closure, the picture is mixed.

Kennedy told TNH that deliveries from government-controlled areas to the northeast are up. “However,” he said, aid “is not reaching all the health facilities serviced and run by the international NGO community up there.”

Akjemal Magtymova, the World Health Organisation’s representative in Syria, confirmed that her organisation’s access to the northeast from Damascus has improved, but noted that the same may not hold true for NGOs working in the area.

“Given the closure of Yaroubieh since January, we... have successfully transported medical supplies and equipment to the northeast over the past few months and hope to continue doing so”, she told TNH by email.

Magtymova said that WHO distributed more than 55 metric tonnes of medical aid across the northeast in May, mostly to areas outside al-Assad’s control, while an additional 85 tonnes intended for the northeast have been re-routed by air from Iraq to Damascus and will be “distributed evenly to all facilities as per their functions”.

“Nonetheless”, she added, “other humanitarian actors which operate in northeastern Syria may not be able to meet the supplies level they used to have in the past, thus leaving gaps to meet the needs.”

On 23 June, Save the Children, the International Rescue Committee, the Norwegian Refugee Council, and 17 other NGOs warned that “lives will be lost” without a 12-month extension for the two northwestern crossings and Yaroubiyeh’s reactivation.

“Medical providers [in the northeast] report critical shortages of PPE, ventilators, hospital beds, and medication,” said Rachel Sider, the Norwegian Refugee Council’s Syria policy and advocacy advisor.

“Lives will be lost” without a 12-month extension for the two northwestern crossings and Yaroubiyeh’s reactivation.

“Despite a handful of cross-line deliveries since January, only through the re-authorisation of UN access through Yaroubiyeh do we have a real chance at filling these gaps”, Sider told TNH.

All eyes on Russia

Germany and Belgium have drafted a resolution based on the UN-NGO demands, supported also by the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. The draft would extend UN use of Bab al-Hawa and Bab al-Salameh for 12 months and re-activate Yaroubiyeh for a trial period of six months.

“The United States believes it is crucial that the UN Security Council act to renew Resolution 2504 in the coming weeks, and include in that renewal the re-opening of the al-Yaroubia crossing point”, a State Department spokesperson told TNH. “Since Russia and China forced the closure of that crossing point in January, the humanitarian crisis in northeast Syria has worsened dramatically.” The US backs Kurdish-led forces in the northeast.

The UN official said that the length of the extension is particularly critical, as the last six-month reprieve for the northwest aid operation hobbled staffing, procurement, and planning.

“The duration of an extension has an operational significance that may be underestimated”, they said.

Much will come down to the complicated dynamics of the Security Council and to Moscow’s crucial role. China backed a Russian veto in January, but it is unlikely to block the extension on its own. On Monday, Chinese UN Ambassador Zhang Jun said some form of cross-border assistance is still needed but noted that there are different opinions about the current system.

Russia’s UN ambassador said that other diplomats should not “waste their time.”

In other words, Moscow’s next move will be decisive. So far, Russian diplomats have been vague about what they intend to do, especially regarding the two Turkey-Syria crossings. (In April, Russia’s UN ambassador Valery Nebenzia said that other diplomats should not “waste their time” by pleading for Yaroubiyeh to re-open.)

Several sources familiar with the situation, and who requested anonymity because they were not authorised to comment publicly, told TNH they expect ongoing Turkish-Russian talks on the status of Idlib to influence Moscow’s position more than the current negotiations in New York. The Russian mission to the UN declined TNH’s requests for comment.

On Monday, Nebenzia told the council that the cross-border operation is “incompatible with international law” and accused the UN of stalling the shift to Damascus-controlled cross-line aid that Moscow has asked for.

He did not explicitly reject compromise of some sort. But as backchannel talks continue and aid workers fret, time is running short for a deal to be reached.

al/bp/as-js