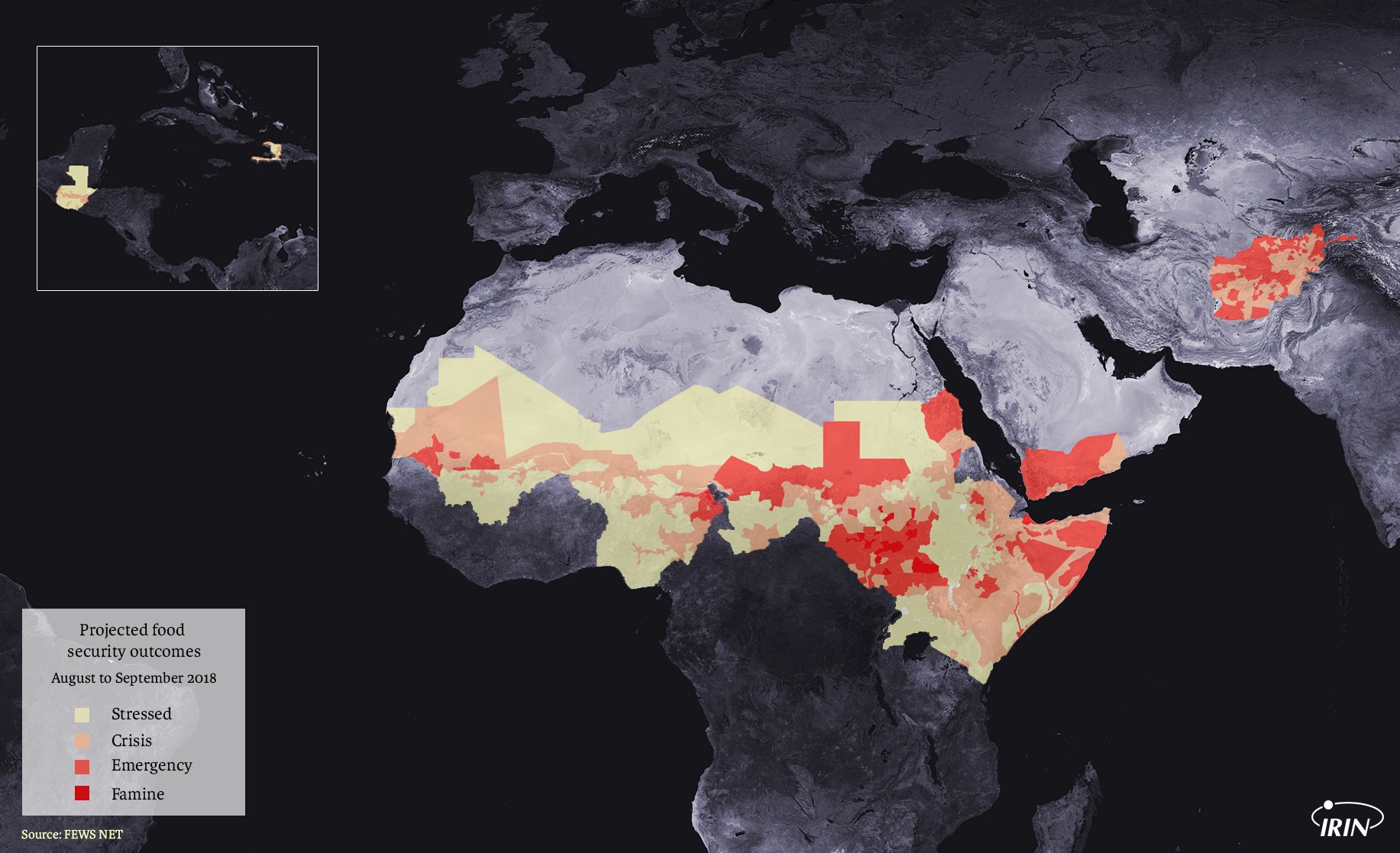

In the runup to a 2011 famine in Somalia that killed over 250,000 people, there were 78 warnings. Last year famine nearly happened again, not only in Somalia but in Yemen, South Sudan, and West Africa’s Lake Chad region. Now, a multi-billion dollar venture is betting that big data and smart money can make famine a thing of the past.

The Famine Action Mechanism initiative, or FAM, is led by the World Bank and draws on its $1.8 billion kitty for famine-prone countries. It is taking a fresh look at how famines happen and what it would take to prevent them, including artificial intelligence (AI)-driven analytics, social safety nets, and new forms of financing. The FAM project is rooted in the belief that donor funding decisions now rely too much on “personal networks as well as political discretion”.

Abdurahman Sharif, head of a consortium of NGOs which tackle nutrition and other needs in Somalia, told IRIN he welcomed new ways to convince donors. “Early warnings can always be tricky, and we’re not always the best at getting early signs,” he said. “Decision-makers,” he added, “won’t take decisions unless they see data”.

Somalia, along with South Sudan, Afghanistan, Niger, and Mali are likely pilots for the data analysis.

Critics, however, say no amount of machine learning and creative financial architecture will change donor decision-making, and warning systems and monitoring tools already exist. It’s political will, not algorithms, they say, that’s the missing ingredient.

World Bank president Jim Yong Kim says modern-day famine is a “collective failure of shameful proportions”. Relief aid typically begins only “when pictures of starving children appear on television”, Kim said at a New York launch event alongside the UN’s September General Assembly. A “proactive” response could save millions of lives, he added, and would cost donors up to 30 percent less than a last-minute scramble. Speaking with representatives of UN agencies and the International Committee of the Red Cross, Kim described the FAM as “an unprecedented global coalition to say, ‘no more’”.

The project launch was strong on rhetoric and short on detail. Few specifics are available on the World Bank website, although IRIN has obtained a June “concept note” that outlines the strategy and tasks across two main areas of work: prevention and early action. On Saturday 13 October, Kim will host another event on the FAM, this time as part of the World Bank’ annual meetings in Indonesia, with ministers from Afghanistan, Chad, Niger, Somalia and the UK.

The Bank says FAM will invest in at-risk regions to strengthen prevention and resilience and plans to swing into action when a famine is on the way. Its most headline-grabbing element is an artificial intelligence tool, Artemis, to improve forecasting. The Bank has recruited Google, Amazon, and Microsoft to analyse a mass of weather, agriculture, market, and conflict data.

More reliable predictions produced from data, the Bank argues, will remove ambiguity, win swifter response from donors, and trigger payouts from future insurance policies.

One long-term observer of food crises, who requested anonymity, said more money isn’t the solution where relief operations are “at the absolute limit,” and that “another half a billion dollars will struggle to make a big difference to South Sudan” when logistics are already stretched and access and security difficult. The analyst also doubted that data on its own – “better and better figures” – would change inherently political decision-making, pointing out that some famines are deliberate, basically “starvation for political and military aims”.

In a politically charged conflict like Yemen’s, it’s not about “how good your figures are”, the analyst said. Nobody wants to look bad because a famine is declared on their watch. This “deep reluctance” among governments may be shared by others, including aid agencies.

Saul Guerrero, a technical director at NGO Action Against Hunger, told IRIN the World Bank is far from being the first to try to model data around hunger. But, given its clout and access to funds, he said it might be able to “create a critical mass” and drive change that is overdue.

Current systems, based on a methodology known as the Integrated Phase Classification, “need some help,” said Guerrero.

Measuring and declaring famine

The strict technical definition of famine has become more scientific over the years. The five-step Integrated Phase Classification (IPC) system, developed in east Africa, is now used in 37 countries. By combining food consumption with mortality and nutrition surveys, the IPC method, and its West Africa affiliate, the Cadre Harmonisé, scores the severity of the situation. The worst, phase 5, is labeled “catastrophe/famine”. All indicators must cross a certain threshold to reach that phase 5 categorisation and trigger a declaration of famine.

It’s not all down to numbers, however: several pockets of South Sudan were graded at phase 5 in a 29 September IPC update, but famine has not been officially declared. Pockets of people in Yemen may live under phase 5 conditions, but data collection is probably too patchy to confirm it.

The decision of how to interpret the often patchy data comes down to an in-country committee of experts and government officials. As many as 120 people were involved in South Sudan’s IPC committee. In these groups, politics, vested interests, and differing opinions can muddy the eventual IPC categorisations. The task is even more tricky when forecasts months into the future are needed. Officials may fail to agree not only “what the pattern is” but also “what the pattern means”, according to Guerrero.

The most prominent international effort working to supply data to the IPC system is a network funded by the US. Since 1985, the Famine Early Warning System (FEWSNET) has provided analysis, bulletins, and alerts. In an emailed response to questions, a World Bank spokesperson said the FAM would build “advanced analytics” and comb new sources of data. However, there is no intention to replace existing initiatives: “FEWSNET, IPC, and other food insecurity estimators are key to the success of FAM,” the spokesperson wrote. FEWSNET declined to comment for this article.

Feeding the code

The FAM will draw on a wider range of data sources than current systems: more remote sensing options, datasets tracking conflict, and possibly even social media, in the pursuit of the best model. Early results from the FAM’s AI data modelling are mixed, according to the World Bank concept note. Part of the experiment is to see if the machines can reproduce past IPC results. For a start, analysts fed algorithms various data to see if they could arrive at the same determinations as the conventional (human) IPC analysts. The World Bank spokesperson said the work was at the “proof-of-concept” stage, and continued ground-truthing was needed.

If humans struggle to agree on what the data means, can machines do any better?

The initial code hit the target 40 percent of the time for South Sudan and 55 percent of the time for Somalia. The preliminary conclusions are unlikely to surprise food security analysts.

In Mali, satellite imagery of areas that are largely desert provided little indication of food consumption. In South Sudan, more violence and higher prices did match up with a worsening food situation, as expected. But in Somalia, there was little correlation between conflict and hunger levels in the midst of near-continuous conflict.

Guerrero acknowledged that the hype around AI could be excessive. Nevertheless, he believes that technology companies can “inspire confidence”, and he welcomes having “people in the room who really understand the technology”. (AI is based on cutting edge mathematics: one model being applied to the data is called “Support Vector Machine with Radial Basis Function and cross-validated L2 penalty”).

Do we still care about the F word?

What is a famine?

How to declare a famine: A primer from South Sudan

Food and nutrition jargon buster

Background on the IPC system

If humans struggle to agree on what the data means, can machines do any better? Not on their own, says Guerrero: “nobody expects it to be a mechanical process”. He says computational power and a complex analytical process could provide a clearer picture: “from greater complexity, greater simplicity.”

Guerrero, who has lobbied UN Security Council members on the issues, said decision-makers feel “the current way of monitoring the risk of famine is not reliable enough… too prone to political pressure”.

“You need evidence”

Sharif, the Somali NGO leader, said, “I can’t recall the amount of letters as NGOs we sent to different capitals” to try and mobilise donors to avert famine in 2017. Sharif said he welcomed the prospect of greater funding and more authoritative data that could help convince donors.

“You need evidence to be able to convince them six months in advance, or one year in advance.” The current evidence only works, he said, when you’re already “very close to the crisis”.

The catastrophic effects of late funding in 2011 proved persuasive to donors in 2017, Sharif said. The UN reports that $1.3 billion of humanitarian funding went to Somalia last year, up from $681 million the year before, and a famine was not declared. Sharif said donors gave him the impression it would be “very, very hard” to raise the same amount again.

There’s little long-lasting effect from all that emergency spending, Sharif added. “Are we preventing another famine, two, three years down the line?” Sharif asked. “I don’t think so.”

bp/js

Barren fields, rising debt, and desperate measures: What daily life looks like in the drought-stricken provinces of Herat and Badghis

Barren fields, rising debt, and desperate measures: What daily life looks like in the drought-stricken provinces of Herat and Badghis