Famine is among the most loaded words in the humanitarian lexicon, with the power to conjure up unbearable images of human suffering, desperation and global failure.

In theory, it should be the humanitarian equivalent of the fire alarm – to be used only in absolute emergencies.

Last week, the head of the World Food Programme (WFP) smashed the glass – warning that Yemen was facing a famine if current trends continue.

The result? Glass everywhere, but no fire brigade: no uptick in global interest, no new focus, no pressure for conflict resolution. Humanitarians say it was the same last year when the UN made a similar warning about South Sudan.

Does “famine” still have the same ability to push the world into action or has the word lost its power to shock, and if so why?

Letting the fire burn

Technically, famine has a clear definition, occurring only when certain measures are met. They are: at least 20 percent of households in an area face extreme food shortages with a limited ability to cope; acute malnutrition rates exceed 30 percent; and the death rate exceeds two persons per day per 10,000 persons.

But the word is also used by the humanitarian system to galvanise global attention. The most famous example was the 1985 LiveAid campaign, formed to help ease the Ethiopian famine in which over 400,000 people died. A media report referring to a “biblical famine” is credited with sparking the campaign.

Precisely because it has the power to be so influential on public opinion, use of the phrase is carefully guarded to have maximum impact.

“We have already lost the power to spark action by using any other word,” said Saul Guerrero, Director of Operations at the charity Action Against Hunger UK (known by its French acronym ACF), putting it on a par with genocide in its potential power.

“If we say there are this many children at risk of death – even if you show the footage – most people who have grown up in the last 20 years have seen plenty of this.

“So [famine] is the card up your sleeve that you only use when the normal communications fails. People are holding onto it for it for dear life, knowing that the moment we lose its [power]…we literally lose our last remaining card when we want to call attention to a crisis.”

Perhaps it is already lost, or at least that is what the Yemeni experience suggests. Abeer Etefa, Middle East spokesperson for WFP, confirmed the decision was aimed at pushing the world into action, but said its use had been based upon new evidence.

“A new assessment done via mobile phones interviewed over 1,100 people randomly selected from 10 of Yemen’s governorates – many of them areas of conflict that we can’t access, showing the scope of the problem,” she said. “There are common themes – no water, food shortages, deterioration, crisis, high prices – (the) situation is getting worse.”

"So [WFP global head Ertharin Cousin] made the decision to talk about the risk of famine to focus attention on this growing crisis."

Many of the world’s media carried coverage of the speech. A trip to Yemen a week earlier by the UN’s top humanitarian official Stephen O’Brien received only a fraction of the coverage.

But the world appears to have been totally unmoved. Going by Google searches, there was precisely no impact. In fact the number of people looking up either “famine” or “Yemen” remained almost static. On the diplomatic side, virtually no governments have reacted.

WFP chief Ertharin Cousin made the statement on August 19, but it had no impact on searches for Yemen or famine

This is not a totally new trend. Kenneth Menkhaus, professor at Davidson University in the United States and an expert on the Horn of Africa, said the famine in Somalia in 2011 in which 260,000 people died was actually less covered in mainstream media than the one in 1991 and 1992.

“In theory [the word famine] should grab even more attention now because it is rarer,” he said.

“When you compare today to the 1980s and early 90s where we had a series of famines in places like Sudan, Ethiopia and Somalia, it is now much more unusual.”

Loss of interest

There are a number of potential reasons for the loss of the power of the word, not least the changing nature of food shortages.

As the world has become better at predicting food crises and established early warning systems, famines caused mostly by weather conditions have declined. The majority of acute food shortages, Guerrero said, are now caused by violence.

It is far harder for journalists and foreign humanitarian workers to be on the ground when these crises are in conflict zones. Even local staff often have little free movement. In Yemen, for example, aid workers and journalists have been targeted, and humanitarian access is negligible.

Menkhaus said this has had a significant impact on our ability to really show a crisis to the world. While Cousin herself visited the southern Yemeni city of Aden, she wasn’t accompanied by a journalist pack.

It has also affected the reliability of information. During the 2004 Sahel crisis, Geurrero said, despite some political issues, you “could sample huge areas" and end up with "pretty evidence-based prediction." “Since 2005 onwards, for the most part we are having to provide information based upon much smaller sample sizes,” he said.

This has led to a lack of figures about the numbers at risk. In Somalia in 2011, Menkhaus said, “the fact is we didn’t know quite how many people were at risk as we had extremely limited access to the affected areas.” In Yemen, too, Cousin was careful to avoid giving hard numbers.

The narratives of these conflicts are also less simple than those in previous famines, Menkhaus added.

“The storyline of a collapsed state and warlordism in 1991 was very compelling,” he said. “By 2011, for many, the focus was on state-building… Humanitarian issues were seen in some quarters as an unwanted distraction.”

In Yemen, the dizzyingly complex nature of the conflict – where northern rebels are fighting with the former enemy and ex-president against the current president, who himself is in exile, alongside Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries – makes it harder for foreign audiences to understand.

A broken record?

There is another option – perhaps the word has lost its resonance due to overuse. By regularly warning of the "fear of famine", have the UN, NGOs and the media made people numb to the word?

Chris Barrett, an agricultural and development economist at Cornell University and an expert on food crises, said that was “probably” true, but asked “what better options exist?”

For him, even if the word is no longer as powerful, it is still worth using. “The general population and global leaders don’t know what the technical definition of famine is – and there’s not universal agreement among supposed experts anyway – but why should that matter? People grasp that something horrible is happening and lives are at risk. That’s the key thing.”

The word should be used as much if not more so than currently to “jar us out collective complacency," Barrett said.

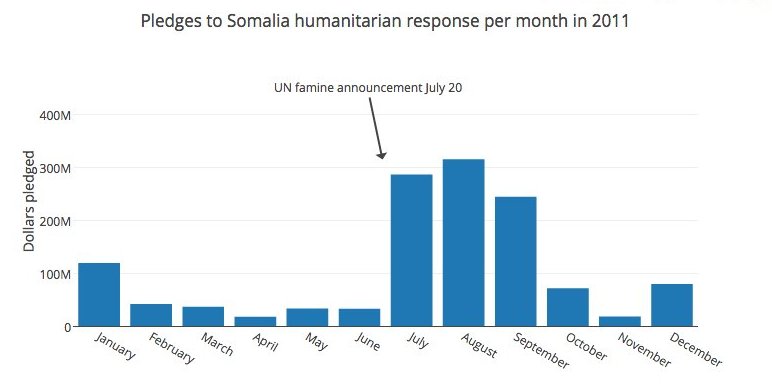

And while the impact on the general public may be limited, perhaps the classification is more aimed at those with money to offer. In 2011, after declaring a famine in three parts of Somalia, the UN’s appeal received far more donations (see chart below).

The country’s humanitarian appeal ended the year 86 percent funded, an unusually high percentage.

The UN will be hoping to spark a similar spending spree in Yemen. Only 18 percent of the $1.6 billion humanitarian appeal for the country is currently funded, while Saudi Arabia has yet to deliver any of the $274 million it pledged to fill a separate UN flash appeal.

Guerrero believes the desperate need still justifies using the word, even if it ultimately weakens its power.

“You have to be mindful of the long-term implications, but… if we always hold back because we are worried we won’t galvanise people in the future, then we might not galvanise them today.”

jd/at