The Ebola outbreak, which was first declared by Guinea’s Ministry of Health on the evening of 22 March 2014, continues to ravage the country, in large part because information campaigns have failed to bring about comprehensive changes in behavior and beliefs.

“Some communities are still convinced that there is no Ebola, that Ebola is a myth,” said Damien Queally, the deputy regional director of Plan International, who is coordinating the organization’s Ebola response activities.

“People are still doing traditional practices and washing dead bodies," he said. "People are still not reporting cases to the hotlines or treatment centers.”

So despite months of intensive attempts to educate communities about Ebola, including its modes of transmission and prevention measures the virus continues to spread from person to person, community to community.

Queally suggested one reason for this might be the choice of messenger.

“In a lot of humanitarian settings, we often don’t appreciate the value of local civil society groups and local NGOs,” he said, citing the success that Plan has had working with traditional leaders in Sierra Leone to promote behavior change in particularly resistant areas.

“Perhaps something similar needs to be undertaken in Guinea,” he said.

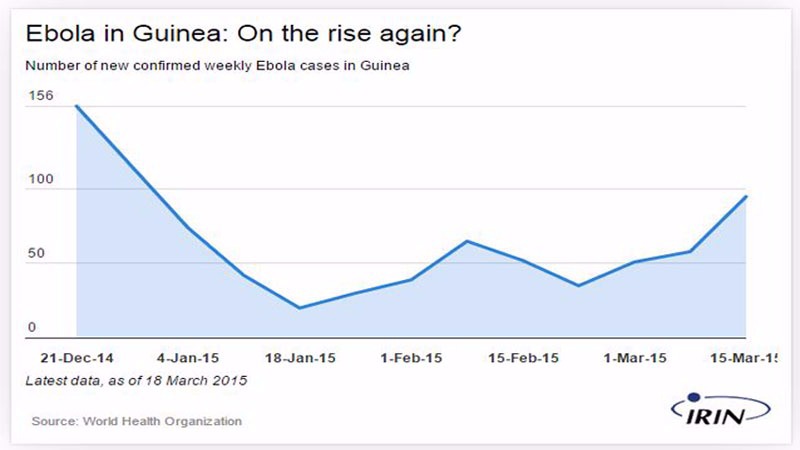

More than 2,200 people have died from Ebola in Guinea, according to the World Health Organization. In January, it seemed the caseload was finally starting to drop. But then, on 15 March, it rose to its highest level since the start of the year, with 95 new reported cases in one week.

“If you are seeing that the virus persists in Guinea, it’s because of a lack of knowledge,” said Ibrahima Soumah, who lives in Guinea’s capital, Conakry. “Look at Liberia and Sierra Leone [where case numbers have fallen], and compare that to the situation in Guinea. People here continue to wash dead bodies without any safety measures because they don’t know better.”

Still a “new” disease

While Ebola has been recorded in central and eastern Africa since 1976 this is the first time it has made its way to humans in West Africa.

“First and foremost, Ebola is a disease which is not known in Guinea,” said Mamadou Diallo, a cashier at a maternal health clinic in Conakry. “We keep hearing about it in the media…but people are still too uninformed about Ebola to better fight it. One must first believe in it.”

Even health workers had little idea for nearly three months that the “mysterious fever” they were seeing was Ebola. Once it was confirmed, in March 2014, it proved to be quite difficult to get people to accept.

“Our main challenge in Guinea has been getting the right message across,” said Henry Gray, the Ebola task force coordinator for Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). “It’s very difficult to pass along an unpopular message, especially in places that haven’t heard about Ebola before.”

He added: “It’s interesting to compare [Guinea] to places like Uganda where the message is really understood. If you have an outbreak there, it’s very quick to contain because people get the message.”

This message includes things such as reporting all suspected cases to health authorities, not touching the body of a living or dead Ebola victim, washing your hands with a chlorine or bleach solution and allowing Ebola patients to be treated in a specialized clinic.

A need for behavior change messaging

In January, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) published a report evaluating the Ebola response of the Red Cross, since March 2014, in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone.

One of the key findings was that while social mobilization messages had been carried out well in many places, more emphasis was needed on Behavior Change Communications (BCC), or the “strategic use of communications to promote positive health outcomes.”

Despite the Red Cross being among the lead social mobilizers at the start of the outbreak, the number of on-the-ground staff who were trained in BCC was “limited,” the report found.

It goes on to say: “In early 2014, some departments within the IFRC seem to have been slow to realize the importance of beneficiary communication for Ebola, and were slow to allocate sufficient resources to it.”

In August, the number of trained Red Cross BCC mobilizers decreased further, when the IFRC switched their response focus from communications to safe and dignified burials, following a multi-agency response coordination meeting.

The IFRC maintains that BCC should be a “cornerstone activity for halting the transmission of Ebola” and “the only activity that will eventually stop the spread of the disease.”

Ongoing distrust of foreigners

But a year in, many Guineans still fear the very people who are trying to help them and the messages they are trying to pass on.

“There was, and still is, quite a bit of mistrust,” Gray said. “People think it [Ebola] is a tool or some sort political manipulation.”

Fadel Gueye, a building engineer in Conakry told IRIN: “I keep hearing of this Ebola business, but it seems to me that it’s just a way for people to get rich off money that is meant for the fight.”

Others still believe it was outsiders who purposely brought Ebola into Guinea.

“Ebola has persisted and continues to persist because Guineans think that it is an ethnic problem [a problem that only affects people of certain ethnicities],” said Lansana Kourouma, a doctor in Conakry. “The day that Guineans…believe in this disease and stop thinking that the Red Cross’s spraying of suspected areas is what brings the virus…and when they begin to respect the prevention measures, is when it will finish.”

Because of this distrust, there have been a number of reports of villages attacking health workers, as well as social mobilization and burial teams, chasing them out of the community and in some cases, killing them.

Contact tracing woes

Health officials say that a key component in the fight to zero cases is extensive and successful contact tracing. This means identifying every single person that has been in contact with an Ebola-positive patient and following up with them for 21 days.

But many families in Guinea continue to hide their sick loved ones, making it hard for contact tracers to do their job.

“Communities are aware that if they report someone who has died, that person will be taken from them and they won’t be able to do the usual rights and washing of the body as they would normally do,” Queally said. “Some people….believe too much in that tradition to stop.”

Complacency dangers

In other areas of the country, where the outbreak, at one point, finally seemed to be under control, flare-ups have occurred, often because people have started to let their guard down.

“We’ve been seeing, in some places, a decline in hand washing, people starting to touch each other again,” said Corinne Ambler, the regional communications coordinator for Ebola response for the IFRC. “Maintaining the buy-in of the community is one of the most important things [because] it’s the behaviours of communities that [control] this outbreak.”

Ebola responders say they know the tactics they have been employing so far - finding and treating patients, conducting safe burials for those who’ve died, active surveillance and looking for new cases, contact tracing, health promotion, passing on the right messages and access to health care – do work.

“It’s just a matter of staying vigilant, not becoming complacent and getting people to report suspected cases,” Ambler said. “I think we need to carry on using the holistic approach that we have been using because that is what has proven to work. It’s what has made previous hotspots clear of Ebola.”

The challenges ahead, as MSF pointed out in a special report released today, are huge.

“To declare an end to the outbreak, we must identify every last case, requiring a level of meticulous precision that is practically unique in medical humanitarian interventions in the field,” said the report, entitled “Pushed to the limit and beyond – A year into the largest Ebola outbreak.”

zc/jl/am