NGO workers provide health services to millions of people through public hospitals, clinics and other health facilities in urban and rural areas.

"Afghanistan has made impressive progress in the health sector over the past seven years," Peter Graaff, country representative of the UN World Health Organization (WHO), told IRIN.

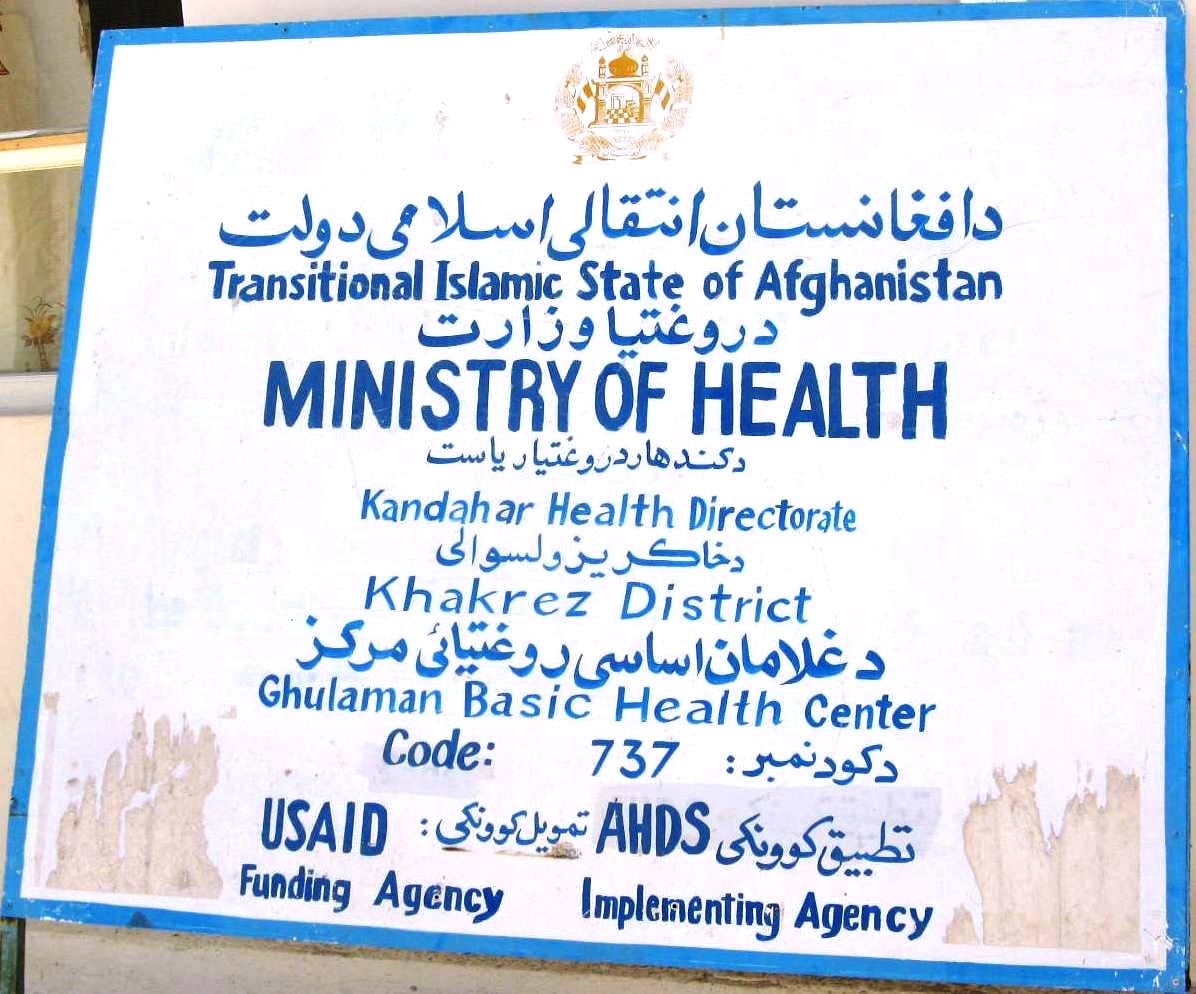

Donors have also praised progress: "With World Bank support in 18 provinces since 2003, the number of health facilities has nearly tripled from 148 to 421... Health care for expectant mothers has expanded, with the number of deliveries assisted in facility [in hospitals, clinics and health centres] by trained health workers jumping from six to 23 percent," said Abdul Rauf Zia, a spokesman for the World Bank in Kabul.

The number of pregnant women who received at least one prenatal care visit rose from just 8,500 in 2003 to 188,670 in 2008; around 20,000 community health workers - half of them women - have been trained and deployed, "increasing access to family planning and boosting childhood vaccinations", Zia said.

Aid dependent

Despite evident progress, Afghanistan's health indicators are still ranked among the worst in the world, according to aid agencies - and the health system is heavily dependent on foreign aid.

About US$1 billion worth of aid money has been spent on health services and on re-building the health sector over the past five years, according to MoPH.

The MoPH effectively has three budgets: a small government budget to cover running costs, financed out of government revenue; a much larger development budget funded by multinational donors via the government; and an external budget funded directly by donors for specific health projects.

"It is a donor-dependent public health system," said WHO's Graaff.

"The aid dependency ratio in Afghanistan is one of the highest in the world," said the World Bank's Zia, and the situation is fuelling concern about the long-term sustainability of the existing health services.

Many donors have committed themselves to long-term aid programmes because of their strong military, strategic and political engagement, but this should not lead to reliance on permanent donor funding, experts warn.

Lower or negative growth in donor countries might adversely impact future aid flows, said Zia, and observers say military withdrawal by some NATO-member nations could also gradually affect aid flows.

|

One of the reasons why NGOs have been awarded contracts to deliver health services is the shortage of professional health workers in rural areas.

Some experts say NGOs are favoured by donors who think NGOs are better able to deliver than the government. But most NGOs pay their staff several times more than government employees, prompting a brain-drain from some government offices.

"The public sector is in a weak position to compete with the donor-supported NGOs for scarce resources," said a WHO bulletin in September 2007.

Some argue that this situation is not sustainable in the long term: "NGOs currently have short-term contracts and lack long-term vision in healthcare delivery. They have few incentives to invest in facility development or in the maintenance and repair of biomedical equipment," said the WHO bulletin.

NGOs are believed to be good at implementing quick impact projects, which some donors and politicians like to sell to the public to garner support, according to experts.

"NGOs only offer makeshift solutions; donors must help the government to build a viable healthcare infrastructure," said Haroun Koshan, an independent medical expert in Kabul.

On the other hand, Rafi Aziz, deputy director of Save the Children in Kabul, confirmed his agency's long-term commitment: "We stand ready for a long-term partnership," he said, adding: "The short-term or long-term objectives of a project depend on its nature and contractual period and not on the identity of its implementer."

NGO scorecards

"Some NGOs are wonderful but the same cannot be said of all [of them]," said Graaff.

Despite its limited capacity and access restrictions in insecure areas, the MoPH has been monitoring NGO performance through a balanced scorecard approach since 2004. This allows MoPH and donors to measure and manage quality, and hold contracted NGOs accountable.

"Data from annual facility assessments, patient-provider observations, and patient exit interviews are synthesized to produce a one-page scorecard on the primary care health system at national and provincial levels," said a joint report by MoPH, the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University and the Indian Institute of Health Management Research in 2006.

The report presented a mixed picture of weak and strong performance by NGOs involved in health projects.

For instance, there were deficiencies in the provision of some services such as delivery care, laboratory services, and the registration of tuberculosis patients. But there were also a number of positive areas such as "performance in overall patient satisfaction; availability of essential drugs and family planning supplies; physical examinations and the taking of patient histories; provision of antenatal care; user fee guidelines; and exemptions for poor patients."

In January 2009, the government named five local and international NGOs which had failed to deliver health services according to their contracts.

In a blunt message Health Minister Mohammad Amin Fatimi said "The NGOs outsourced by MoPH for the implementation of BPHS [basic package of health services] should abide by the health laws and regulations of Afghanistan and respect the contracts signed with MoPH. We will not tolerate any misconduct or lack of respect to the contracts and to the health and nutrition strategy/policy of Afghanistan by any NGOs."

ad/at/cb/oa

This article was produced by IRIN News while it was part of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Please send queries on copyright or liability to the UN. For more information: https://shop.un.org/rights-permissions