As the Iraqi military announced (not for the first time) that it had finally routed the so-called Islamic State in Fallujah, the city’s former residents can be forgiven for not breathing a collective sigh of relief.

After 18 months under IS rule, a siege by Iraq’s armed forces that left food and medicine in dangerously short supply, and a perilous flight into the desert, many of the newly displaced are now living without tents, enough water, or latrines.

Humanitarians on the ground have said the response to the displacement of almost the entire city – between 60,000 and over 80,000 people depending on who is counting – has been disorganised, at best. Others are more brutal in their assessment. “Aid workers are running around like headless chickens,” said one worker recently returned from the new camps.

As they struggle to play catch-up and the long-awaited march on Mosul draws closer (Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi said Monday that the Iraqi flag will fly over the country’s second largest city soon), many humanitarians are worried that they are woefully underprepared for the challenge.

“When Mosul happens, God help us,” Karl Schembri, spokesman for the Norwegian Refugee Council, told IRIN.

“The entire humanitarian community has failed Iraq – from donors, to governments, to the implementing agencies on the ground,” he continued. “Fallujah has exposed all of our shortcomings with massive consequences for the tens of thousands of civilians displaced.”

There are between 800,000 and 1.5 million people in Mosul – again, it depends who you ask – numbers that dwarf the population of Fallujah.

IRIN has taken a closer look at the Fallujah aid operation and asked what went wrong and whether the civilians caught up in Iraq’s next battle will receive the aid they need and deserve.

To what extent do funding and security concerns excuse a weak and insufficient response to the displacement of civilians from Fallujah? And to what extent were deeper-rooted bad habits, poor coordination, and a culture of risk aversion really to blame?

Is it about the money?

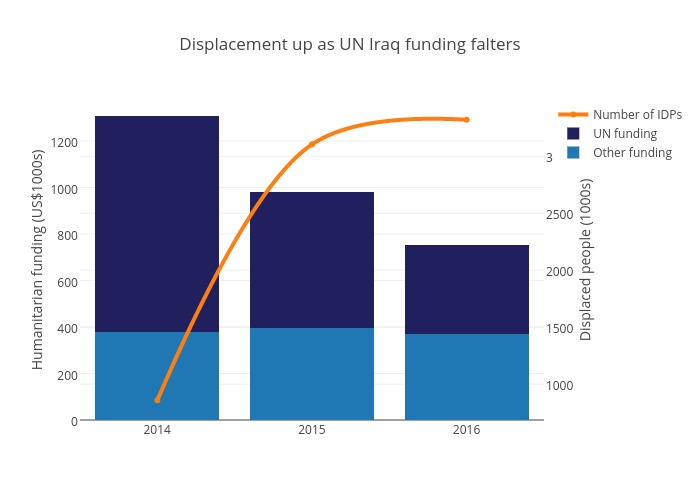

Fallujah is only the latest in a series of mass displacements in Iraq that began in January 2014 when IS entered from Syria and met little resistance. According to the latest figures, more than 3.3 million Iraqis, around 10 percent of the population, are displaced inside the country.

The humanitarian system, led by the UN, has been struggling to cope. A team of senior UN and NGO officials was sent to Iraq to review the humanitarian operations in May 2015, and soon after produced an internal “Operational Peer Review” (OPR) report, obtained by IRIN, whose findings have not been previously reported.

The report stresses “the need for a scale-up in preparedness for what are almost certain increases in humanitarian needs as a result of further conflict; a preparedness which is hampered by a lack of funding.”

And it is funding that, according to Lise Grande, the UN’s humanitarian coordinator for Iraq, meant the system wasn’t fully ready for Fallujah.

Fallujah was long known to be high up on the Iraqi army’s list as it continued its battle against IS, with local militias and United States airpower on its side.

Indeed, in April – as it became clear that supplies were running low inside the city – Grande told IRIN that the UN was “in the process of expanding our footprint” in areas where displaced were expected to decamp to.

“We are getting more… camps and tents, and moving supplies in.”

But this didn’t happen as planned – some supplies were prepositioned and camps established – but not nearly at the level needed. Grande says this is because the money simply wasn’t forthcoming.

“The funding wasn’t there and therefore we were absolutely stuck,” she said.

The budgetary woes are real. Iraq’s UN-led humanitarian appeal has received only 36 percent of the $861 million it says it needs for 2016, (at least $36 million has been newly pledged).

While limiting, it is proportionally the best-funded major humanitarian appeal of 2016.

And with several humanitarian crises in the Middle East alone, donors are cash-strapped. Last April, senior European Union aid official Jean-Louis de Brouwer warned that money was a major worry for aid in Iraq.

"The needs are skyrocketing and the resources are not increasing," he said. "I'm afraid there is also — not donor fatigue — but donor exhaustion."

Individual agencies have funding concerns too. Their funding tends to come in short-term grants from governments. They are expected to spend it in that timeframe, making it difficult to set aside stocks of food, tents and supplies for clean water,and latrines.

“We all knew that Fallujah was about to happen,” Schembri said, but explained that the country’s chronic displacement crisis made it difficult to prepare (Fallujah was only one of the cities that was talked about as the Iraqi army’s next move).

“We have been hearing about [the battles of Fallujah] and Mosul for the last two years, so do you fill hundreds of warehouses with latrines while people elsewhere need them now?” he asked, rhetorically.

Playing it safe?

But there’s more to the problem than just funding.

Joel Charny, director at the NRC and an aid agency veteran, told IRIN that even if funding was low and aid agencies were surprised by the speed of the exodus (30,000 in a matter of days), that’s no excuse for the sluggish response.

Between late May, when the Iraqi government announced its assault on IS in Fallujah, and now, something could have been done.

“I insist that there was enough time to get something organised to avoid the chaos that we are seeing now,” Charny told IRIN.

Part of the difficulty may be the operating environment. Although only 60 kilometres from Baghdad, Fallujah is in western Anbar Province, Iraq’s largest, which also includes another former IS stronghold, Ramadi.

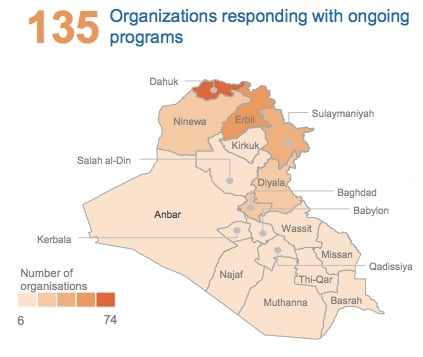

The 2015 OPR stresses that “the humanitarian response is concentrated in accessible areas and… it does not necessarily target those most in need.”

In the case of Iraq, accessible tends to mean the relatively peaceful semi-autonomous Kurdistan Regional Government, where many aid organisations have set up camp.

Little seems to have changed since the review. Indeed, Grande told IRIN that “one of the major constraints we have is that very, very few frontline partners are working in Anbar.”

For the sake of illustration, there are seven aid organisations (including the UNHCR, the UN’s refugee agency) officially working on providing shelter in Anbar Province (although IRIN understands two of these are not involved in the Fallujah response), where – before Fallujah at least – there were 578,208 internally displaced persons.

In comparison, there were 48 agencies – nearly seven times as many – at work on shelter in Dohuk, a KRG province with 397,290 displaced.

There are grumblings that major organisations just haven’t stepped up in Anbar, at least not in time to help those displaced from Fallujah.

Oxfam, for example, has a Baghdad office but no presence in Anbar. It said it was concentrating its efforts in the (Kurdish-controlled) northeast of Iraq. An Oxfam spokesperson told IRIN by email that the charity is “very concerned by the situation in Fallujah at the moment, but, much as we might wish to be, Oxfam cannot be everywhere. We are currently grappling with the biggest emergency aid effort in our history – one which is largely driven by refugees and people fleeing their homes.”

Another major NGO, Save the Children, told IRIN that while it didn’t currently work in Anbar, it was carrying out a needs assessment in the camps around Fallujah with an eye to providing help there.

In their defence, even if organisations wanted to suddenly dash to Anbar to help with what has become an increasingly desperate situation, it’s not a simple undertaking.

There’s red tape to cut through in Baghdad, not to mention the time it takes for aid groups to establish a presence in the province, find staff, and establish trust with the local authorities and population.

The Danish Refugee Council is one group that has been working in Anbar this year. Stef Deutekom, acting Iraq country director, said the problem with the response was the lack of aid groups on the ground.

“Few international organisations were on the ground in Anbar only a few months ago, mainly due to the insecurity and lack of humanitarian access prior,” Deutekom told IRIN in an email.

“The challenges faced are multiple,” he said. “From an insecure environment; access to Anbar, as the [government-controlled] Bzeibiz Bridge has been closed at various moments in the past; to a lack of sufficient coordination at various levels.”

International Committee of the Red Cross spokesman Ralph El Hage also stressed the importance of maintaining a presence on the ground: “The principle we operate on is being extremely close to the people, because if you are not close you will not be able to respond quickly.” ICRC is not a formal member of the UN-led aid machinery but is active in Anbar.

The missing tents

It’s now been more than a month since the Iraqi army announced its battle on IS in Fallujah. It’s been more than 10 days since 30,000 people escaped in a matter of three days, with an estimated 32,000 in the weeks before that.

Every aid organisation on the ground says the response has been far from ideal. The UN had estimated there were 50,000 civilians inside the city; now it appears there may have been more than 80,000.

As Deutekom puts it, with “hundreds if not thousands of families living out in the open for multiple days without access to basic services, the humanitarian response has not been satisfactory.”

The NRC's Schembri is less measured. “What will distinguish us from ISIS if we abandon the very people who fled from them just at the moment they need us most?”

One of the greatest complaints is that vulnerable civilians have been left to survive temperatures well above 45 degrees Celsius without so much as a tent to shelter them from the elements.

This could, and should, have been avoided.

With 30,000 exiting Fallujah in a matter of days and surprising aid workers, it may not have been feasible to have tents for all those waiting. But the length of the delay is hard to justify.

“We wanted more tents in Anbar, but everything that we could do under the existing budget was done,” said UNHCR’s Iraq representative Bruno Geddo.

At first, the Iraqi government – desperately short on funding itself – was providing tents to the newly displaced. So was the Saudi government. But when these were not sufficient, frontline agencies expected UNHCR to release many of the 10,000 tents it keeps at all times in Baghdad, or the 10,000 more in the KRG capital, Erbil. After all, they are warehoused for situations just like this.

But the tents still haven’t come. As of the end of last week, only 1,533 had been sent.

Why? No one seems to agree.

A high-ranking Iraqi employee at UNHCR, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said the organisation was simply taken by surprise.

“When the [military] operations began and people started to leave, we were surprised by the number of families. It was much bigger than what we had planned for, and it confused us.”

He said that getting the tents across the Bzeibiz bridge required permission from the Iraqi authorities that was not forthcoming. For the most part, the UN can’t deliver supplies itself due to the security situation.

The same UNHCR employee said the company the UN has contracted is not paying the kickbacks at checkpoints, so these are “playing a major role in delaying the aid being delivered on time.”

Grande said the tents should now be moving. But the fact that it took so long is worrisome and points to gaps in coordination – exactly what the UN system is meant to be doing, and an issue highlighted by the 2015 review.

For her part, Grande recognised that coordination had been a problem. “I think that everyone who has been looking at the Fallujah situation realises that this was an operation which we have been scrambling to try to bring onto track, and we recognise there are many gaps in the response, in our operational footprint, and gaps in coordination as well,” she told IRIN.

Onwards and upwards?

Humanitarians were also remiss in making plans for Fallujah based on how events played out in Ramadi, another major IS stronghold, according to UNHCR’s Geddo.

“We were influenced by the situation of Ramadi. We thought the long-term siege on Fallujah would produce a situation similar to Ramadi, whereby manageable numbers of people would get out as they could,” he explained.

Some 40,000 people were displaced from Ramadi as the Iraqi army and its allies fought off IS for nearly eight months, but there was nothing like the sudden exodus that happened with Fallujah.

When that’s not what happened, a group of organisations that count emergency response as their business was remarkably slow to adapt.

Just as Fallujah turned out not to be at all like Ramadi, Mosul will likely present its own unique challenge for humanitarians. With up to 1.5 million residents and tall buildings, a different sort of warfare is likely to engulf the city.

“Mosul is going to make Fallujah look like nothing,” warned the NRC’s Charny.

Humanitarians say they are preparing, as much as possible. DRC’s Deutekom said that his group and others had been planning for Mosul for “quite some time now”.

“There is clearly the risk that if and when displacement out of Mosul will happen, the number of displaced persons fleeing in multiple directions is going to be a tenfold of what we have seen around Fallujah,” he said.

The UN’s Grande promised there is a plan for Mosul, one that takes in various possible scenarios. But ominously, she reiterated once again: “our ability to fund the humanitarian contingency plan depends on funding coming in.”

as/bp/ag