While the EU and the UN channel funds into deportations, evacuations, and patrolling the central Mediterranean, the vast desert border in Libya’s neglected south remains largely unsecured, leaving people smugglers, stripped of other work opportunities, to operate with impunity.

Great attention has been focused on curbing the arrival of migrants to Europe by sea and repatriating those detained in Libya – especially as the Mediterranean death rate soars to levels not seen since the height of the 2015 crisis and militia violence flares in Tripoli, forcing detention centres to be evacuated.

Yet the real solution to the migration crisis, argue Libyan officials, journalists, and activists, is securing Libya’s south. Why, they ask, are the EU and the UN spending so much money on initiatives that can do little to truly curb migration if the country’s borders are allowed to stand open?

“Illegal immigration must be stopped in the desert, not just the sea, and all the world knows this,” said Captain Wajidi al-Bashir al-Montassir, the head of Tripoli’s Airport Road Detention Centre.

Yet in the economically devastated south, there’s little evidence of efforts to curb the only thriving business, people smuggling.

That business is focused on delivering people to Sebha, which since 2011 has been left to flourish as a central hub of goods and people smuggling, with a volatile security situation rendering it one of Libya’s most lawless towns.

Entire districts are no-go areas for rival tribes; free movement across the whole town is impossible; and it remains a hotspot for tribal violence that can erupt with little warning.

Major Mohamed Tamimi has worked for decades in Sebha and now runs a key checkpoint north of the town, from where he powerlessly watches smugglers gather migrants in a warehouse just 200 metres from his checkpoint.

Speaking to IRIN over the phone in May, he said that he was not aware of any representatives from the EU or the UN visiting Sebha to meet with security forces or illegal immigration officials, even directly after the fall of Muammar Qaddafi in 2011, when security was adequate.

“We are completely on our own here. Immediately after 2011 we had a modest amount of support from the Libyan transitional government and then that stopped,” he said. “Some of us are at least being paid again now, but many, especially newer recruits, haven’t been paid for two years. Amongst our guys, there is a huge will to work, but this is a dangerous job that no one wants to do without a salary.”

Libyan border security and Coast Guard officials are fiercely critical of current EU and UN initiatives, including deportations, evacuations, and rescue operations at sea. Some even accuse the international community of encouraging rather than curbing migration.

“Based on the support we see here from the EU and its weak cooperation with us, we really think the EU does not want to stop illegal immigration,” said al-Montassir, the head of the Tripoli detention centre. “We need practical help and technical equipment, like satellite and tracking systems. We’ve been collecting smugglers phone numbers from migrant’s phones, but we need equipment to be able to track these numbers and catch them.”

Tebu country and southern neglect

Since official border guards fled their posts in Libya’s 2011 uprising, the country’s vast southern borders have stood wide open, facilitating unregulated illegal immigration in unprecedented numbers.

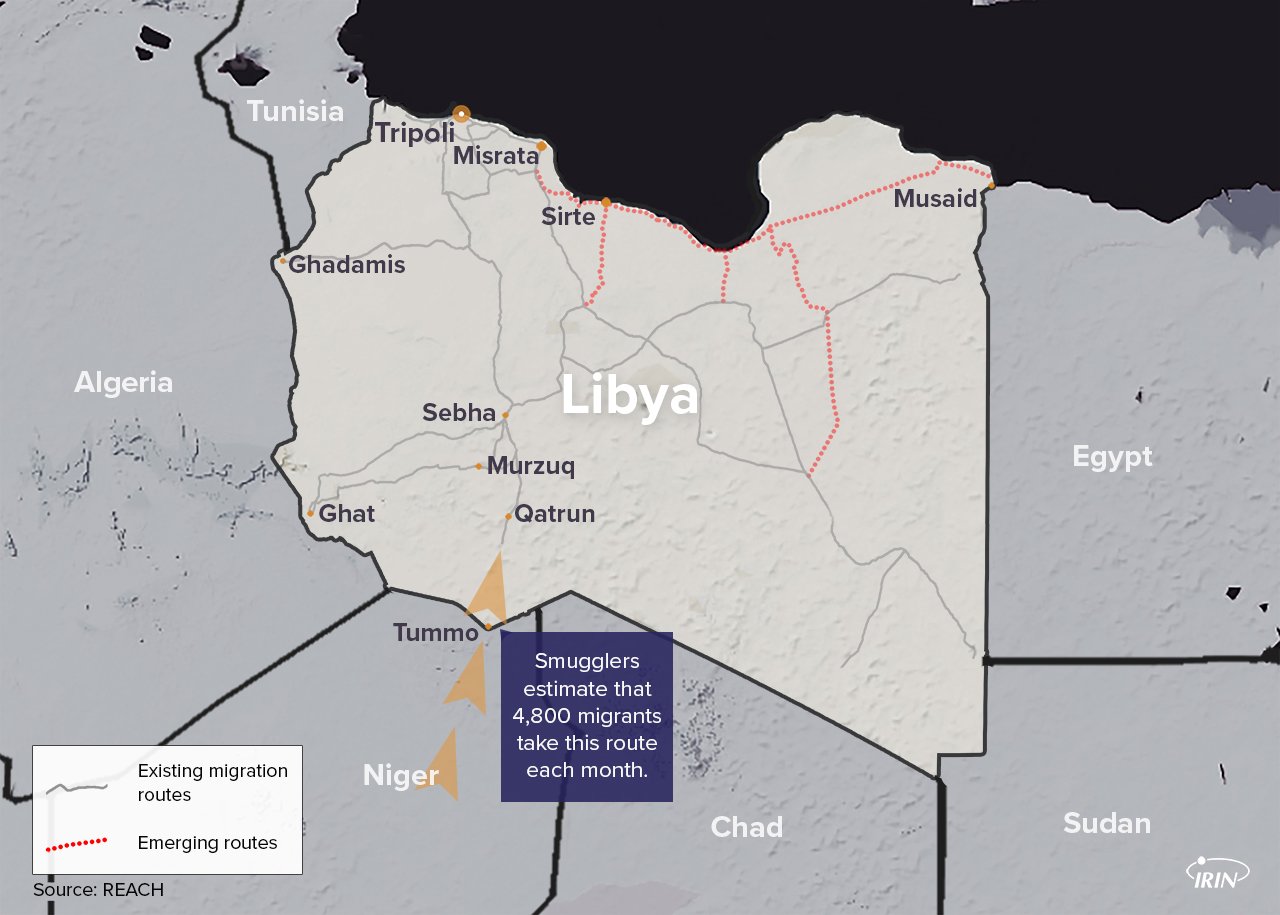

Every week tens of Toyotas packed with 23-30 migrants each speed across the Sahara near the Tummo border crossing with Niger, which local voluntary militia have manned since 2011.

Heading north, they follow tyre tracks towards a 600-kilometre stretch of weather-beaten, sand-strewn tarmac formerly known as “Qaddafi’s Road”, leading to Sebha.

The Toyotas weave on and off the road to avoid checkpoints, but apart from this token nod of respect to the region’s largely powerless local security teams, people smuggling here is conducted in the open.

This is Tebu country, mainly populated by members of this indigenous Saharan ethnic group, which, since 2011, has become one of Libya’s most marginalised minorities. The members of volunteer militias at Tummo and checkpoints up to Sebha are Tebu, as are nearly all the people smugglers working this route.

None of Libya’s faltering post-2011 governments have maintained control over or given support to this southern area for years. That has left the Tebu to become semi-autonomous, operating basic local governance and security systems that tribal elders preside over.

Daily life is tough. Staple goods, electricity, and fuel are often in short supply; fuel is only available on the black market at inordinate cost. Only the most basic education is available, and most young people have been unable to attend colleges or universities in Sebha since tribal conflicts erupted there in 2012.

Stripped of study and work opportunities and faced with rising poverty, local Tebu youth have increasingly turned to people smuggling, working what has become the busiest migrant route into Libya.

If you’re a migrant who has made your way into Libya, chances are you’ve met a Tebu. Nearly all the smugglers plying the busiest migration route from Agadez in Niger to the outskirts of the Libyan people smuggling hub of Sebha belong to this indigenous Saharan ethnic group.

Although increasingly ashamed of the role their young men now play in illegal immigration and desperate to improve their situation, community leaders insist people smuggling will not stop unless there is significant local and regional development to help improve the dire economic situation in southern Libya and offer other opportunities.

“Given that the bulk of illegal immigrants are being brought in by Tebu people smugglers, if Italy and the EU really want to reduce the flow, they must tackle the roots of the problem and work closely with municipalities in the south, where the influx of migrants arrive at the border,” said Libyan journalist Jamal Adel, who is Tebu.

“Municipalities in the south can make real changes on the ground if they are sufficiently assisted, including supporting border guards with logistics and training and improving opportunities for young people,” Adel said. “With the deteriorating economic situation, for too many young unemployed Tebu, human trafficking has become the only way to make a living.”

A senior Tebu figure in the southern Libyan town of Murzuq – on the main route from the Niger border crossing at Tummo to Sebha – Mohamed Ibrahim, described most smugglers as intelligent and resourceful people, including many undergraduates forced to abandon their studies.

“No one wants to be a people smuggler, so a real and straightforward solution to illegal migration through Libya would be to provide funds for local development and offer alternative and sustainable opportunities to the smugglers themselves,” he said.

“The international community needs to actually talk to these guys. If they want to study, help them access universities; if they want scholarships to study abroad, facilitate that; if they want to start a local business, offer funds and support, first making them sign contracts to renounce smuggling.”

Ibrahim said this was something that could be done remotely through civil society organisations, if security concerns prevented the EU and the UN from working in Libya’s south. He estimated the costs of providing all Tebu people smugglers with their desired alternatives would be a fraction of the millions the EU and UN continue to plough into deportations, evacuations, and funding governments in Niger or Libya, which, he said, were largely powerless to control the vast Sahara desert.

“If there were sustainable options and opportunities on the ground for these guys, I’m confident this smuggling door could be permanently closed,” he said. However, similar schemes in Niger’s smuggling hub of Agadez have had only limited success.

Nori and Ahmed, two Tebu smugglers working the Niger-Sebhu route, both told IRIN they dream of travelling abroad and studying in a safe and peaceful environment – an aspiration ironically shared by many of those they are illegally transporting into Libya – and would welcome opportunities and support to pursue new careers.

“Talking to the Tebu is the real key to stopping illegal immigration into Libya,” said Ibrahim, noting that any dialogue should include all aspects of society, not only smugglers.

Basic security at the Tummo border crossing point and checkpoints along the road to Sebha – all easily avoided by smugglers – is provided by volunteer Tebu militias from some of Libya’s remotest desert towns. They say they haven’t received support from any of Libya’s competing governments for years.

With no funding, few weapons, little fuel, and only a handful of battered vehicles, older and less powerful than those used by the smugglers, the volunteers are unable to attempt anti-immigration operations or undertake desert patrols. And, with no functioning detention centres anywhere in southern Libya, if they do stop smugglers, they can only order them back to Niger, from where the Toyotas can merely re-enter Libya via a different route.

“Since the revolution, not one person from any government has been here, even though we are trying to protect our people and our land,” Tebu checkpoint commander Agi Lundi told IRIN during a visit to the south in 2015. “1,900 kilometres of desert border is manned by volunteers who don’t have vehicles, weapons, or even petrol.”

He showed folders of immaculately kept records of desert deportations run between 2011 and 2013, explaining how these ceased after his militia stopped being reimbursed by the Libyan government for vehicle rental and petrol costs.

At the Tummo border crossing in 2015, Commander Salah Galmah Saleh admitted that, with no government support, his forces were so powerless, smugglers could easily cross into Libya. He said they were waiting for the then nascent UN-backed Government of National Accord (GNA) to take full control. Three years later, the GNA still has little control beyond the capital.

Several local sources confirmed to IRIN that the situation remains the same now as it was in 2015: border guards still go unpaid, and their sole support is basic supplies provided by the local council and “gifts” of fuel from goods’ smugglers.

Ahmed, 24, started working the Niger-Sebha route five years ago, after his family’s financial hardship forced him to abandon his studies. Other Tebu say they were pushed towards smuggling after being displaced by civil conflict; Nori, 23, moved south from Sebha to the oasis town of Murzuq in 2014 after losing his home and possessions.

“The circumstances that have befallen our youth have pushed them into this activity and, in our current situation, we are unable to offer them anything else,” Hussein Shaha, a Tebu social activist from Libya’s southernmost town of Qatrun, told IRIN. “The Tebu are at the border and at the end of Libya, and we ask the international community to recognise this and look at us with new eyes.”

Little help from abroad

The situation at Libya’s borders, and in the south more broadly, has been largely ignored not only by the various post-Qaddafi governments but also by the international community.

Tens of millions of euros have been poured into the EU Border Assistance Mission (EUBAM), established in 2013 to support Libya in improving and developing the security of its borders. Headquartered in Tunisia since mid-2014 (recently with an “enhanced presence in Tripoli”), the mission has so far accomplished little in terms of boosting the security of Libya’s land borders.

EUBAM Chief of Staff Peter-Bastian Halberg described the EU initiative, which has an operational budget of €31.2 million, as a civilian mission currently finalising its planning for an operational mission.

“More effective border control and security is a technical aspect of implementing the Libyan migration management, and essential to stop transnational criminal networks that put lives at risk,” Halberg told IRIN, clarifying that the EU’s aim isn’t to stop migration but to ensure it that it takes place in a safe way and as a choice rather than a last resort.

However, a former EUBAM employee, speaking on condition of anonymity, told IRIN that the organisation should be investigated for wasting public funds, while a senior Libyan source close to the UN described EUBAM as “a totally unacceptable institution”.

“They are doing absolutely nothing, and are lying to the international community saying they are helping secure Libya’s borders,” the Libyan said. “They’re working in Tunisia, not Libya, just making long reports but actually doing nothing on the ground.”

One of Tripoli’s most senior officials in the Anti-Illegal Immigration Agency, or AIIA, said Libya urgently needed direct and practical border support, pointing out that, before 2011, borders were monitored by twice-weekly land and air patrols.

“The first thing is to reactivate agreements and treaties, especially the treaty signed in 2007 and 2008 between Libya and Italy to protect Libya’s borders, erecting cameras and using modern electronic methods to monitor and control the southern borders,” the official, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said. “None of this happened, none of these agreements were ever put into practice.”

Helped through Niger

Some migrants do cross the Algerian and Sudanese borders, but the Libya-Niger border attracts the largest number by far.

Louise Donovan, a spokeswoman in Niger for the UN’s refugee agency, UNHCR, praised the Nigerien government for allowing evacuations from Tripoli, saying it showed “huge solidarity” as it also hosts more than 108,000 Nigerian refugees and over 57,000 Malian refugees.

“By expanding its asylum space and enabling UNHCR to temporarily evacuate refugees to Niger, the government of Niger is already providing a huge amount of support – which is not necessarily forthcoming from other countries,” Donovan told IRIN.

Due to access challenges, IRIN was unable to reach the south during a recent reporting trip to Libya in May, but smugglers on the ground said they had seen no changes since IRIN was last there in 2015. “The Nigerien army are still escorting smuggler convoys and the numbers of migrants we are transporting has not decreased at all,” said Ahmed, the Tebu smuggler from Murzuq.

Four or five military trucks escort convoys of 40-80 vehicles every week along the most dangerous 670-kilometre stretch of Niger desert, from Agadez to Dirkou. The Niger military says this is to protect the vehicles from bandits who attack convoys and try to steal vehicles, migrants, food, or fuel. Smugglers have a different view. One told IRIN the military rarely intervenes when bandits drive into convoys looking for faltering vehicles to attack.

This military escort, underway since 2013, is free (to Nigerien smugglers), but bribes must be paid at each Niger checkpoint by non-Nigerien smugglers and passengers, smugglers say. These bribes not only bolster the meagre wages of Nigerien troops manning desert outposts but also pay for the military’s basic necessities, including fuel. Some female migrants unable to afford the bribes reported being raped by Niger checkpoint guards, saying that incident was the start of a cycle of sexual abuse that often characterises women’s illegal journeys towards Europe.

Suspicion of foreign motives

The migration crisis, al-Montassir stressed, is a transnational problem that requires transnational solutions. “For example,” he said, “current African protocols allow extensive freedom of movement without papers, which has made it easy for people to come in their thousands, and this should be controlled and monitored. Neighbouring countries should also secure their borders and deploy greater restrictions on entries.”

Ordinary citizens in southern Libya who regularly witness people smuggling and are familiar with the latest trends also criticised current initiatives. “Everyone is making money from migration, and I see the sending back of migrants also like a business. Everyone is using migrant numbers on paper to get more money,” said Shaha, the Tebu social activist. “Migration is a chain, and the Tebu are just one link in that chain, and if there was no demand further up the chain there wouldn’t be so many migrants.”

A tribal elder in southern Libya told IRIN the EU isn’t serious about stopping migration and attacked its policy of giving millions of euros to Niger to encourage it to crack down on people smuggling.

“The [Nigerien] government takes photos of security forces in the desert and maybe curbs migrant numbers for a month, then lets the numbers return to normal until they get more millions, and [then] reduces it again for another month,” the source said. “Qaddafi did the same. He’d get money and just close the borders for a few months. But it’s not in the interests of the Niger government to stop illegal immigration because, if it actually stops, they won’t get any more money.”

Libyan Navy Spokesman General Ayoub Ghassem went further, suggesting there was an international agenda to increase migration.

“The EU and UN want to send a message of encouragement to Africans that, if they get to Libya, they will be rescued in the sea. None of this should happen, but Africans have been brainwashed into just dreaming of living in this land of promise – Europe,” he said. “These migrants are victims of some larger plan we do not fully understand, to empty African lands of their people, and Libya is a victim of its location.”

tw/ag/js

Read the series from the start with Destination Europe: Homecoming

What happens when migrants end up back home with less than when they started? After arduous and traumatic journeys, would-be migrants accept repatriation offers with a promise of support. Only, upon returning home, support is hard to find and they are rejected by their loved ones as failures out of shame. Susan Schulman reports from Sierra Leone on migration's push and pull factors and the lives of those affected.

Read the other instalments: Homecoming, Evacuation, Frustration, Desperation, Deportation, Demoralised, Misery and misunderstanding part 1 and part 2, and Overlooked