“There are no opportunities for youth here,” said Yar, a 20-year-old South Sudanese refugee from Jonglei, stuck in the Nyumanzi refugee settlement in northern Uganda.

Her words were echoed in conversations I had throughout my two-week visit to the settlements.

Since war broke out in South Sudan in December 2013, approximately four million people, one third of the fledgling nation’s population, have been forced to flee their homes.

Today, half of those who’ve fled are living as internally displaced persons in South Sudan, and the other half have become refugees in neighbouring countries, especially Uganda.

Uganda now hosts more than one million South Sudanese refugees and more cross the border every day, fleeing violence, insecurity, and drastic food shortages in their native country.

Yar arrived in Uganda in 2014. She lost most of her family in the war and is now living alone in the refugee settlement, without much hope for the future.

“There is no opportunity for youth to study in secondary school or to get jobs,” she told me. “Young people are just sitting around doing nothing.”

The issue of youth idleness was a recurring theme in nearly all my conversations: with refugees, NGO representatives, the UN refugee agency, UNHCR, and the Office of the Prime Minister, or OPM, which coordinates the refugee response in Uganda.

Approximately 61 percent of the South Sudanese refugee population in Uganda is under the age of 18. With no signs of South Sudan’s ethnically driven civil war ending anytime soon, some refugees could be displaced for 10 to 20 years, or more.

Wasted lives

If this youth population remains idle for the next decade or two, without support to address their trauma and hatred towards certain ethnic groups, there is a significant risk they could return to South Sudan to perpetuate violence through the next generation.

There are already some reports of refugees being recruited by armed forces in South Sudan, and some are willingly returning home to take up arms.

Research has shown a strong correlation between a growing unemployed/idle youth population and civil conflict.

As US Ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Hayley begins a trip to South Sudan and Uganda today, she must confront this issue in the refugee settlements and prioritise the inclusion of youth in future peace endeavours.

Large and idle youth populations are often easily manipulated, especially if there are unaddressed grievances against certain groups (ethnic, religious, political). Some individuals become so desperate that they will join armed groups to provide for themselves and their families.

With a third of the population displaced – most of them youth – lacking opportunities, traumatised by war, and ethnically divided, the situation could become a perfect storm for perpetuating the conflict.

As Michelle Gavin, an adjunct fellow for Africa at the Council on Foreign Relations said: “If you have no other options and not much else going on, the opportunity cost of joining an armed movement may be low.”

For good reason, the humanitarian community’s emergency response to the refugee situation has focused primarily on providing for refugees’ basic needs – food, water, shelter, and healthcare.

However, by now some refugees have been displaced for more than three years. The response must also prioritise youth empowerment programmes, job training, and peacebuilding efforts to ensure they don’t become a lost generation.

Change agents

Today’s idle youth population represents a huge risk factor for further violence, but it does not have to be that way.

With the right training and investment, these young refugees could become productive members of both the South Sudanese and Ugandan societies, and could play a pivotal role in bringing peace to South Sudan.

Some South Sudanese youth leaders have taken the initiative to form organisations dedicated to mobilising their peers to become a positive force for change.

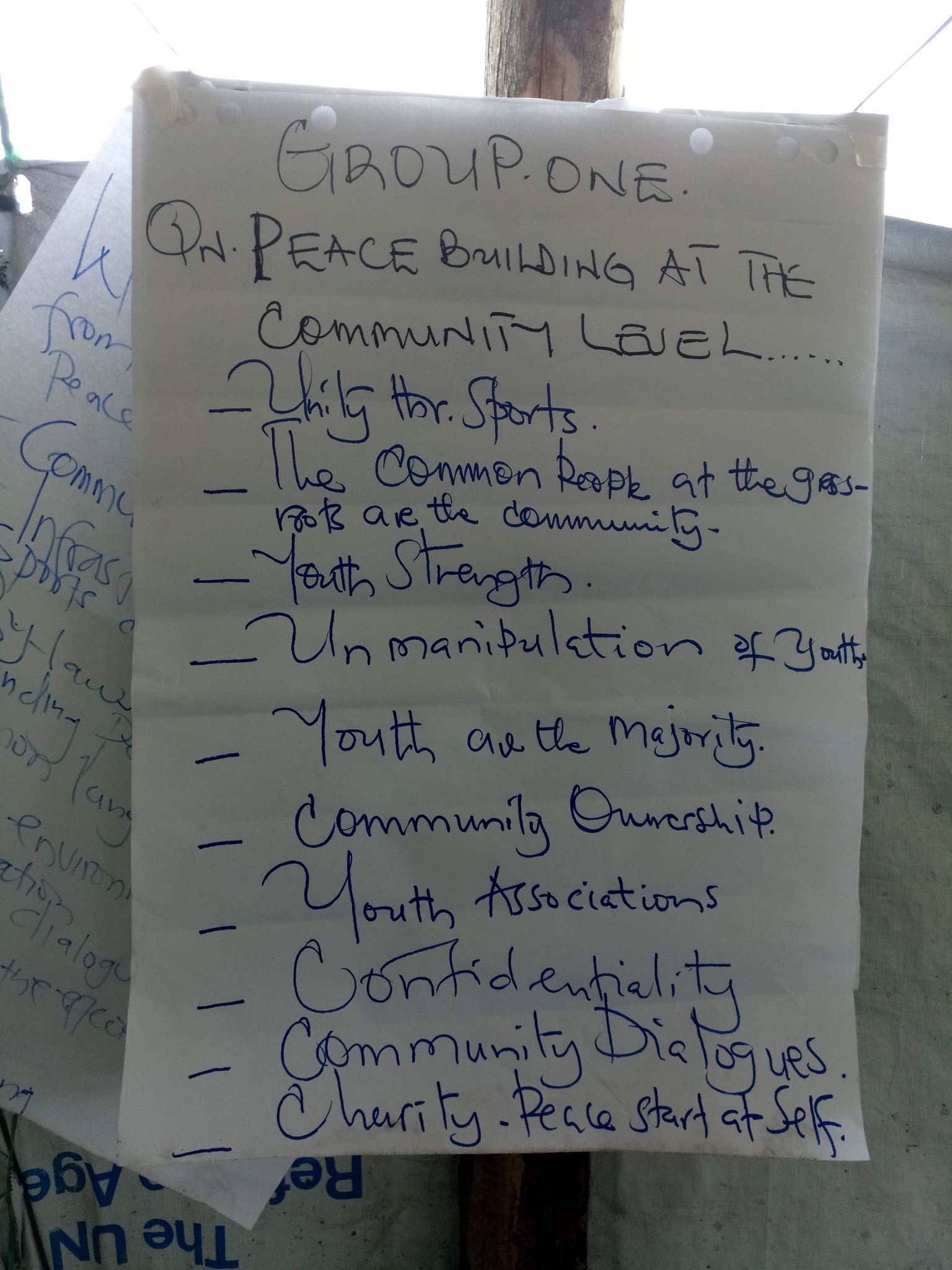

Among these is the African Youth Action Network, which conducts dialogue sessions and trains leaders in peacebuilding and conflict resolution. Operating in both South Sudan and Uganda, AYAN brings together youth of various ethnic groups – men and women – to discuss issues related to the conflict in South Sudan, as well as issues specific to refugee communities.

“So often, youth are being regarded as only victims or perpetrators, but the great potential that we have to bring about positive change in South Sudan is neglected,” Malual Bol Kiir, AYAN’s co-founder and executive director, told me.

Kiir, who is also a member of the UN Advisory Group of Experts for the Progress Study on Youth, Peace and Security, added: “We organise dialogues and train young people on peacebuilding and conflict resolution. So far, we have 150 South Sudanese peace ambassadors across Uganda and in Juba [South Sudan].”

Given the training and opportunity of working with organisations like AYAN, South Sudan’s youth could become the change-makers their country so desperately needs. With two thirds of the population under the age of 30, the country cannot afford to have its youth sitting idle – in refugee camps or at home.

As Ambassador Haley tries to understand the current conflict dynamics and determine how to reignite a peace process, it is imperative that she takes time to meet with South Sudanese youth leaders, and insists on the inclusion of youth in any future peace process.

Donor nations and the humanitarian community responding to the refugee crisis must prioritise the issue of youth idleness and invest in reconciliation and peacebuilding programmes.

We must engage these youths now so that they will play a leading role in bringing peace to their young nation.

mb/oa/ag

TOP PHOTO: An AYAN meeting in Rhino refugee settlement, northern Uganda