Fed up with growing violence, deepening poverty due to COVID-19 lockdowns, and a federal Colombian government they view as exploitative and negligent, thousands of Indigenous people have crossed this vast Andean nation to demand answers from President Iván Duque.

Piled into overcrowded buses, old trucks, and motorcycles in a rambling caravan that stretched for kilometres, they came from at least eight of Colombia’s 32 departments, and some travelled for 10 days before reaching the capital, Bogotá, on 19 October.

They came to demand solutions for rising killings in their communities, unkept government promises, and decades of neglect that have resulted in their western and southwestern regions becoming the deadliest areas in a nation plagued by decades of internal conflict.

Joining them for the final days of their journey, The New Humanitarian found Victor Manuel Ruiz from Mondomo in northern Cauca atop the roof of a brightly painted bus, or chiva, that overflowed with people and foodstuffs as it traversed winding mountain roads and picturesque countryside near Ibagué, 200 kilometres west of the capital.

“The government promised us autonomy and our lands back as part of the 2016 peace accord,” said 20-year-old Ruiz. “We got neither. And now they want to send soldiers instead to occupy our lands. In the past when that has happened, they often keep what the soldiers take.”

Rather than implementing the promises of the deal negotiated with left-wing Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) guerrillas by his predecessor, Juan Manuel Santos, Duque’s response has been one of militarisation against the rebel and drug-trafficking groups.

Duque’s critics say this decision is threatening Colombia’s peace and has made the dangerous situation in the western and southwestern regions even worse.

Read more → Is a new Plan Colombia putting a fragile peace at risk?

Indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities find themselves terrorised by a host of armed criminal groups involved in territorial land disputes, as well as in conflict with government-allied businesses that have encroached upon their lands, and sometimes even with state forces themselves.

Frustration in Cauca began to boil over last October when Cristina Bautista, a well-known Indigenous governor, was killed along with four volunteer community guards after they happened upon two vehicles carrying kidnapping victims and tried to help. The government blames an ex-FARC splinter group for the killings.

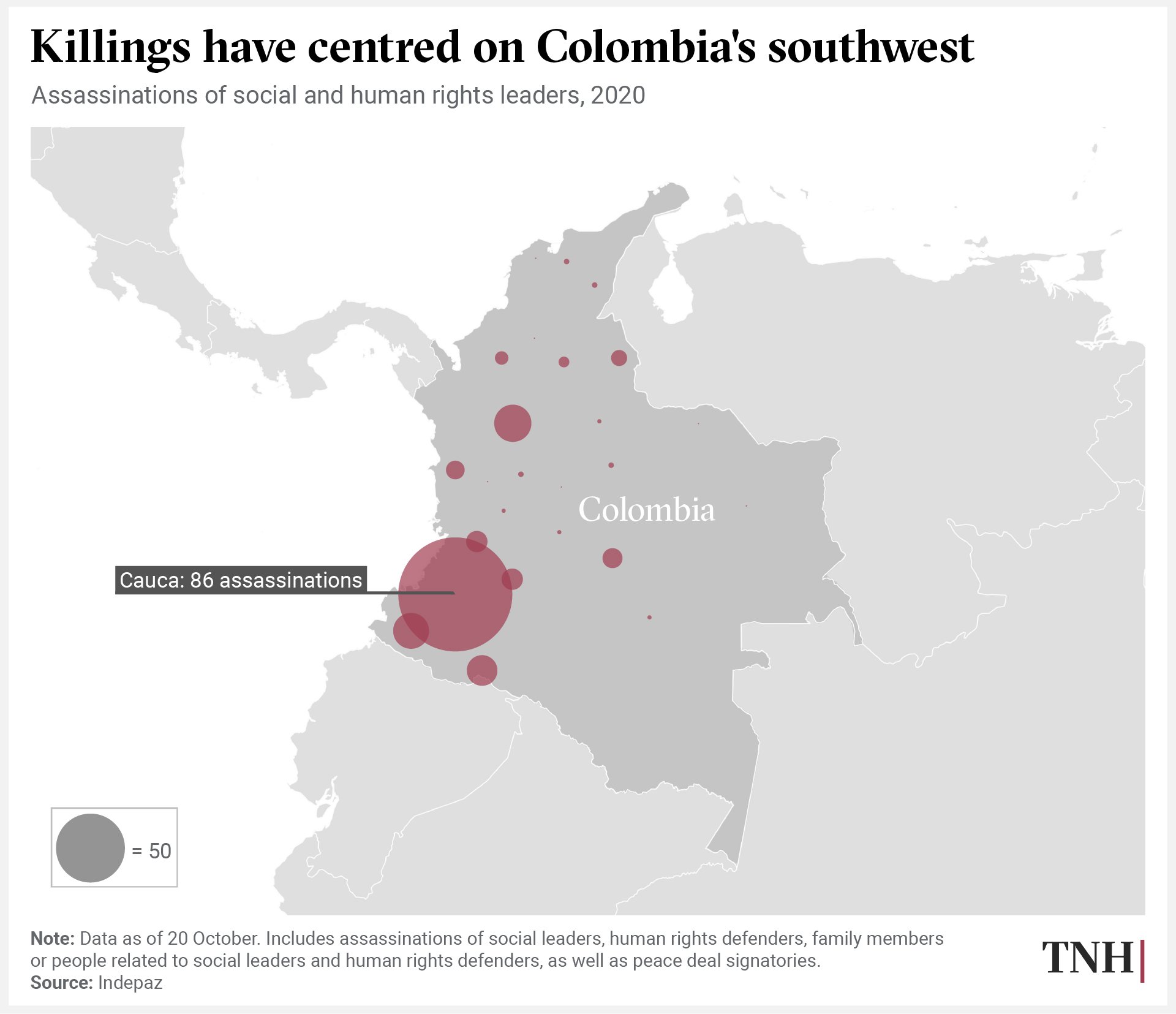

More than 230 Colombian social leaders have been killed already in 2020, 640 since Duque won elections in 2018, and over 1,000 since the peace accord was signed in 2016, according to peace monitoring group Indepaz. That number nationally in 2013, four years before the peace deal began being implemented, was only 10.

Most of those killed have been Indigenous or Afro-Colombian people involved in the peace process in some way, and the western and southwestern regions – also the main coca-growing areas – have been hardest hit.

From a minga to a movement

Ruiz’s chiva was part of a caravan that activists said numbered 10,000 people. Media reports put it at more like 7,000. Most Indigenous people came from the west or southwest, but some even travelled from the southernmost Amazonas region on the borders of Brazil and Peru.

The movement began when Indigenous leaders convened a minga, or mass gathering, on 8 October to address what they viewed as a growing crisis. In the Quechua Indigenous language spoken throughout the Andes, minga means shared work, or a meeting in solidarity for neighbours to undertake a communal task.

The collective, patched together from hundreds of distinct Indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities, convened originally in Cali, the closest major Colombian city to their western regions, demanding to meet with Duque.

Their demands were ignored. Instead, members of Duque’s party claimed, without evidence, that their ranks had been infiltrated by criminal armed groups, and called them “terrorists”. Álvaro Uribe, a former president and leader of Duque’s political party, accused them of being “totalitarian socialists bent on destruction and nothing else”.

Those who called the minga decided to bring their protest to the capital.

As protesters marched on Plaza Bolívar, the main square in the capital, on 19 October to bring their demands to the president, Duque flew to the Colombian port and tourist centre of Cartagena for a private event rather than respond to the mass demonstration.

In response, the minga leaders announced plans to stay in the capital and join ongoing national strikes planned by student groups on 21 October.

Poverty as well as conflict

Andrés Maís, 42, runs an organisation called Sin Techos (Without Roofs) in Cauca that operates a seed bank for local farmers and provides agricultural and small business training to Indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities.

When he heard a minga was being organised, he volunteered to drive a youth group from Popayán, the capital of the department, on one of the chivas to Bogotá.

“The pandemic has been devastating for the community. Extreme poverty has skyrocketed since lockdown measures began,” Maís told TNH in Fusagasugá, the town 50 kilometres southwest of the capital where the caravan stopped for the night on 17 October.

“Farmers in rural areas had no way to bring their goods to market, and urban areas were devastated by unemployment,” he said. “We changed our operation entirely and focused instead on emergency nutritional needs of vulnerable communities. Families were starving while the government did nothing.”

Violence is far from the only issue faced by the Indigenous communities in western Colombia. The regions have long been in conflict with the federal government over the lack of infrastructure and education, and with the private mining companies they say have been squatting on their land illegally since the late 1990s.

According to the 2018 national census, 4.4 percent of Colombians – more than two million people – identify as Indigenous, while an additional 9.3 percent, almost five million more, consider themselves Afro-Colombian.

In one of Latin America’s most unequal countries, Indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities are most impacted by poverty, with the latter enduring poverty rates in excess of 40 percent, nearly double those of the rest of the population. The arrival of COVID-19 and the accompanying lockdown measures imposed by the government have added further economic pain to the poor in the region.

Chronic malnutrition affects children in many Indigenous and Afro-Colombian regions, including Cauca, Choco, and Amazonas. Violence in rural conflict zones, where many Indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities live, has reached record levels since the peace deal was signed in 2016, nominally bringing an end to a 50-year civil war.

But the violence hasn’t stopped. The Colombian ombudsman's office reported 58 instances of mass displacement in southwest Colombia – affecting 15,140 people – in 2019, with an additional 19,000 people displaced nationally this year as of July. Colombia has the world’s second highest number of internally displaced people, after Syria.

Yann Le Boulaire, MSF’s coordinator in the western Buenaventura region, told TNH that in addition to an acute shortage of medical services, there is particular concern over mental health needs – long neglected in a region where stigma about admitting such issues is strong.

“Decades of violence have created generations suffering from post-traumatic stress, and this can at times perpetrate a dangerous cycle,” he said.

Duque, a right-winger who won election on promises to dismantle key aspects of the controversial peace accord, blames the regional problems on narco-traffickers, leftist guerrilla groups such as the National Liberation Army – known by its Spanish acronym ELN – and ex-FARC groups that splintered off when the rebel army disarmed in 2017.

“In this country and in this region, we have to forcefully confront the drug traffickers who want to capture local power, who want to intimidate the communities,” he said in a response to the emergence of the minga movement in a national address on 8 October.

Duque touts his “New Plan Colombia”, which militarises several regions into conflict zones and ratchets up the use of regressive drugs tactics, as part of this “firm hand” approach to dealing with the lawlessness he claims is at the root of the problem.

Mining interests and colonisation

Territorial conflicts between armed groups aren’t the only battles being fought in Cauca. The region is rich in minerals, and the lands of the Indigenous communities have been historically encroached upon by mining operations and actors that are both legal and illegal.

A recent joint report by Colombian and German research groups stated that these actors vying for the mining wealth of the department are “an explicit cause of death, displacement and threats to social leaders”.

Leaders who oppose these projects receive death threats and oppression from the dozens of armed groups in the region, either because the groups want the territory for themselves, because they are allied with local politicians favourable to the developments, or due to alleged links between these activities and paramilitary forces.

“The peace deal was supposed to resolve that, giving us back our land, but the government has abandoned its promises.”

Many of the minga leaders’ demands involve implementing policies laid out in the 2016 peace deal: greater political autonomy, more agency in how land disputes are settled, investments in infrastructure and education to allow people to escape extreme poverty, and better protection from the state in dealing with the armed groups.

Victoria, who asked that her last name not be used for fear of retaliation, is from the Nasa tribe, which has a long and contentious history with the federal government.

“Some of Duque’s biggest political supporters have squatted on land owned by the Nasa people in Cauca since the mid-90s,” she told TNH, as protesters made their way to the presidential offices in Bogotá, to the backdrop of Indigenous chants and drum beats.

“They have even been accused of working with paramilitaries to violently defend their interests,” said Victoria. “The peace deal was supposed to resolve that, giving us back our land, but the government has abandoned its promises.”

The Duque administration dismisses such claims as being motivated by narco-traffickers who want to destabilise the country.

For Maís, the leader of Sin Techos, today’s crisis is a direct extension of the colonisation of his people hundreds of years ago.

“You look at these problems and you see the same thing happening now as when the Spaniards arrived. [The government] only cares about our land when it has mineral wealth or something they desire,” he said, “Not only are the tactics identical, [but] in some cases it is descendants from the very same families who enslaved my ancestors that benefit from these policies.”

jc/pdd/ag