Mounting rights abuses and political disengagement could push more young people towards militancy in Indian-administered Kashmir, residents warn, following some of the deadliest violence the troubled region has seen in a decade.

Last year was Kashmir’s deadliest since 2008 and the bloodshed has worsened since.

The Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCCS), a local rights group, says more than 586 people were killed in 2018, including militants, Indian security forces, and 160 civilians. The Indian government puts the civilian death toll at 37. This year is already threatening to surpass the last: the rights group recorded 162 total deaths from January until March.

The Himalayan territory spanning India and Pakistan is claimed by both entirely and has brought the nuclear-armed nations to open conflict several times since independence from Britain in 1947. Violence in Kashmir has left at least 40,000 dead since a separatist insurgency against Indian rule ignited in 1989. The Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir, which includes the Kashmir valley, is the country’s only Muslim-majority state.

“International NGOs are very restricted when it comes to accessing Kashmir, but the truth needs to be told.”

Local rights advocates fear a growing humanitarian crisis fed by years of conflict and unchecked human rights abuses.

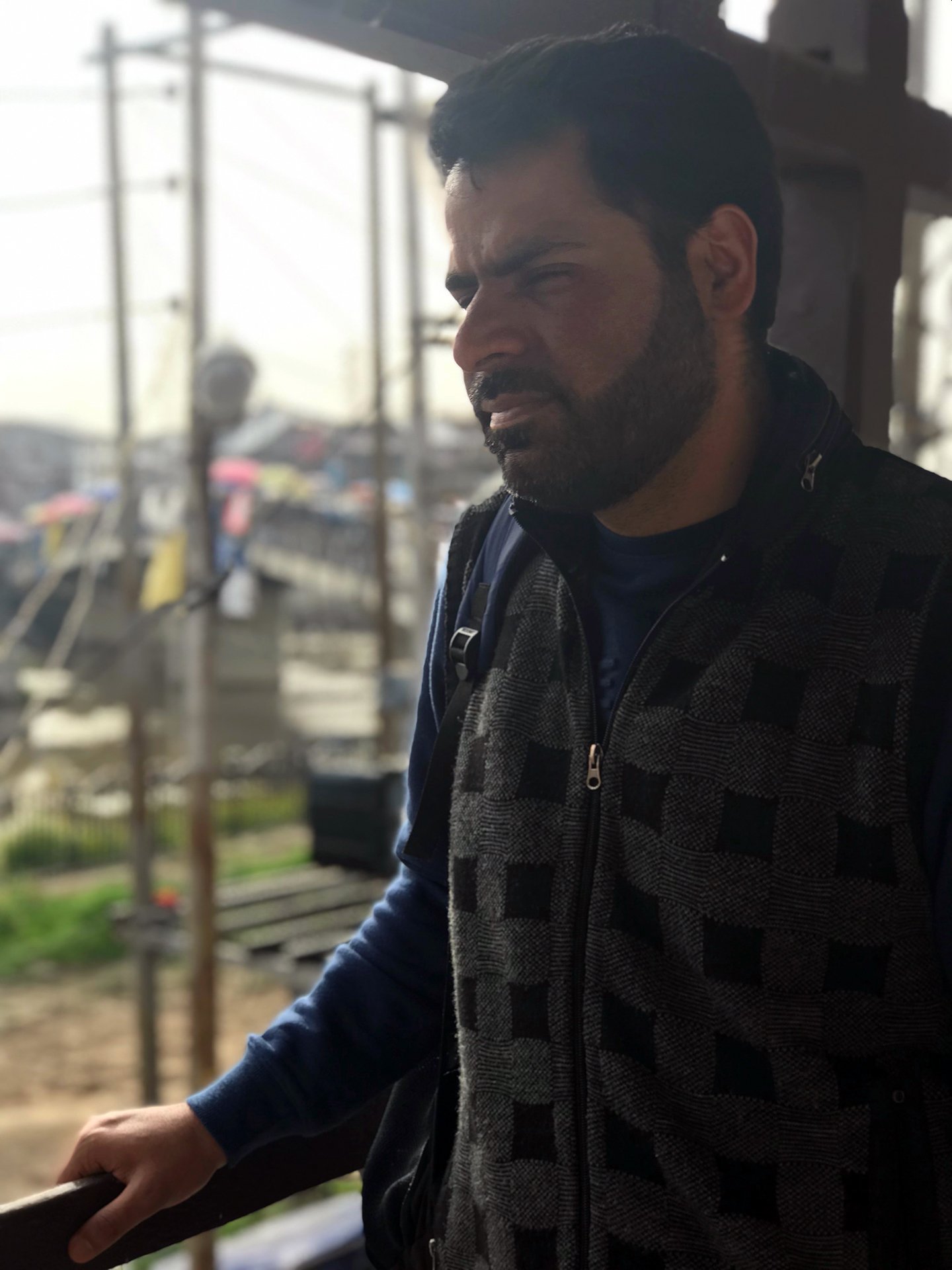

“International NGOs are very restricted when it comes to accessing Kashmir, but the truth needs to be told,” said Khurram Parvez, JKCCS’s co-ordinator. “They don’t need to wait to be invited; they can speak out now.”

Violence this year is fuelled by a rare suicide bombing in February that killed 40 Indian paramilitary police in the southern town of Pulwama. The attack, claimed by the Jaish-e-Mohammed militant group, put Kashmir back under an international spotlight. India blamed Pakistan for allegedly supporting Kashmir militants and the two countries exchanged airstrikes. The parents of the 22-year-old suicide bomber, Adil Ahmad Dar, told local journalists he may have been driven to militancy after being assaulted by police in street protests, which have frequently erupted in recent years.

Some armed groups in Kashmir demand accession to Pakistan; others advocate complete independence for the territory. India has cracked down on both militancy and civilian protests, which ignited with the July 2016 killing of Burhan Wani, the popular commander of the militant group Hizbul Mujahideen, by Indian security forces.

For Mohammad Ashraf Wani, there is no doubt that India’s controversial policing policy is counterproductive and instilling a fearlessness in Kashmir’s youth.

In 2016, he was hit by a hail of pellets from an officer’s pump-action shotgun and collapsed in a pool of blood. Despite multiple surgeries, Wani lost all sight in his right eye and has partial vision in his left.

Shotgun pellets have been used as a crowd control method in Kashmir since 2010 – the only Indian state in which they are deployed. More than 6,221 people received pellet gun injuries in the seven months following the July 2016 unrest, according to the Jammu and Kashmir government.

“India and Pakistan have turned Kashmir into a graveyard.”

“Anyone here who sees their brother, sister, father, or mother in some ways abused by the state machinery creates a situation where the youth are so fed up that they will take to the streets and won’t care whether it’s a pellet that hits them or a bullet,” said Mohammad, who now leads a lobby group for pellet gun victims. “India and Pakistan have turned Kashmir into a graveyard.”

Kashmir’s increasing violence was the backdrop for India’s recent elections, which saw Prime Minister Narendra Modi returned to power in results announced 23 May. Preliminary data shows that Jammu and Kashmir recorded a turnout of only 29 percent compared to a nationwide average of 67 percent. Hundreds of polling stations recorded no voters at all.

In downtown Srinagar’s bustling Lal Chowk, or Red Square, Indian soldiers peer out of barbed wire-strewn sentry posts and patrol the streets gripping automatic rifles. At his nearby office, Parvez of JKCCS told The New Humanitarian that mounting claims of police brutality are a major reason for Kashmiris’ disengagement from politics and a rise in militancy.

Parvez, who has received death threats for his work and was detained for two and half months in 2016 after attempting to travel to the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva, said the actions of the suicide bomber in the February Pulwama attack – Kashmir’s first suicide car bombing in nearly two decades – should be a warning sign.

“Why do we not question how the government’s actions have led him to join militancy? If the government would not brutalise people and instead allow political space for protest, I’m sure that the reason for militancy would decline,” he said. “The low election turnout was a message, loud and clear: ‘We want the resolution of Kashmir and an end to human rights violations’.”

Signs of a humanitarian impact

Parvez blames Indian authorities for ignoring the will of ordinary Kashmiris for self-determination, and the international community for what he sees as a conspicuous silence.

Under Modi’s first term in office, the ruling Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party has been accused of stoking anti-Muslim sentiment across the country, which has seen a spike in hate crimes. In March, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights warned India of increasing reports of harassment and targeting of Muslims.

The constant tension between the army and the civilian population appears to be leaving a lasting humanitarian impact. A May 2016 survey by Médecins Sans Frontières found that 45 percent of the population in the Kashmir valley were under “significant mental distress” and nearly one in five Kashmiris showed symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. Strikes, protests, and resulting curfews have also shut down schools for long stretches, while clashes have interrupted jobs and livelihoods.

A JKCCS report, released last month, documented decades of allegations against Indian forces in Kashmir including “water-boarding, sleep deprivation and sexualised torture”, which the rights groups said are used as an “instrument of control” to quash dissent.

Despite the potency of the conflict, it took until 2018 for the first UN report into the human rights situation in Kashmir to be published. As well as decrying violence committed by authorities in Pakistan-administered Kashmir and armed groups on both sides, Indian forces came in for the most scrutiny. Detailing hundreds of extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, and sexual violence, the report highlighted the Armed Forces Special Powers Act, which gives Indian forces operating in Kashmir immunity from the gravest of crimes.

“In the nearly 28 years that the law has been in force in Jammu and Kashmir, there has not been a single prosecution of armed forces personnel granted by the central government,” the report stated.

India has called the UN report “fallacious” and “tendentious”. In its election manifesto, Modi’s BJP defended government policy: “In the last five years, we have made all necessary efforts to ensure peace in Jammu and Kashmir through decisive actions and a firm policy.”

For Kashmiris who have seen their family members die, however, such broad statements ring hollow.

Abdul Qayoom Bhat, a security guard from Srinagar’s northern district of Soura, claims that his son Umar was repeatedly slammed into a concrete pipe by police officers at a protest in August 2010. The boy died days later in hospital. Bhat said it took him eight years to obtain an incident report for his son’s death. His case against the police is one of the few abuse allegations in Kashmir making its way through a court-mandated investigations process.

At a shack next to the shimmering waters of Srinagar’s Lake Dal, where hawkers offer tourist accommodation on ornately carved wooden houseboats, Bhat angrily recounted his son’s death. He said he hoped others won’t take part in protests: “It’s not worth the risk.”

But he also understands why young Kashmiris are taking to the street.

“Boys, when they see their brothers or fathers in their neighbourhood being killed or tortured, it is that repression that forces them to pick up stones or guns or to hit the street with a hope to stop it.”

(TOP PHOTO: Kashmiri villagers carry a body of top militant commander Zakir Musa of Ansar Ghazwat-ul-Hind group, which claims affiliation with Al-Qaeda, during a funeral procession at Dadsar village in Tral, south of Srinagar on 24 May 2019. )

ac/il/ag