Water shortages and crop failure caused by record-low rainfalls in Pakistan are forcing some farming families to abandon their land, fleeing what officials say is the worst drought to hit the country in years, while others are selling their last breeding animals or seed stocks to survive.

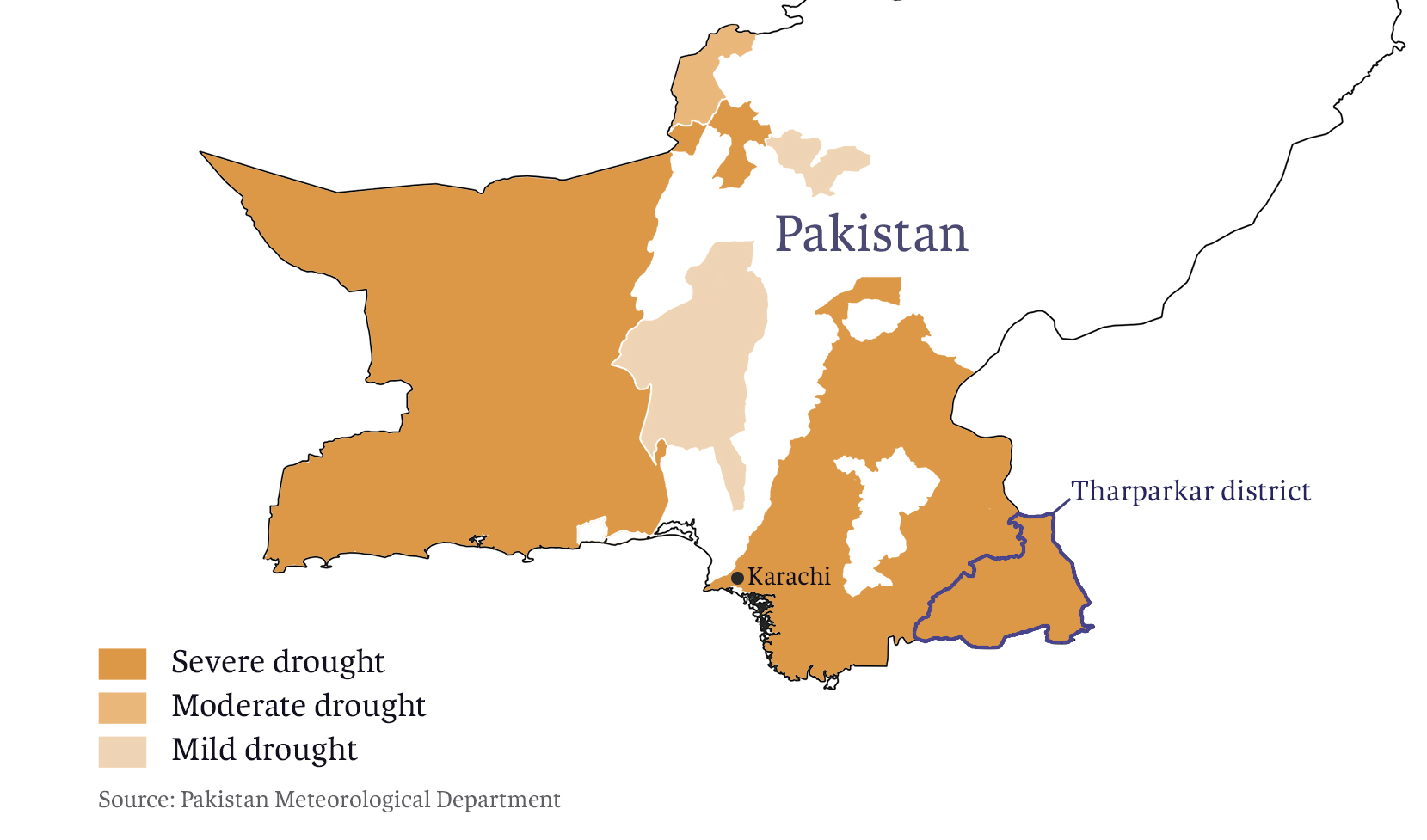

Authorities and aid groups say conditions are deteriorating in large swathes of Sindh to the south and Balochistan to the west, where both provincial governments have declared emergencies. Disaster management officials say at least 2.8 million people are affected in the two provinces’ worst-hit districts.

Pakistan’s Red Crescent Society says the drought in Sindh and Balochistan is “rapidly developing into one of the worst disasters in Pakistan”. Health officials fear rising food insecurity and malnutrition, while authorities say more needs to be done to help families cope at home.

But some are already leaving. In late January Sunita Meghwar boarded a truck along with 55 other people – the entire population of her tiny village near Mithi, the capital of drought-hit Tharparkar district in southern Sindh.

Meghwar said she decided to leave when her village’s wells dried up.

“We have no option other than migrating,” she said, as she stopped for water at a public tap en route to the city of Hyderabad, some 200 kilometres away from her village.

Parts of Pakistan have seen frequent dry spells for years, particularly Tharparkar district, where malnutrition and disease – exacerbated by frequent drought – reportedly kill hundreds of children each year, prompting calls for an inquiry into government actions in the district.

But Meghwar said this past year has been the harshest and most prolonged in memory, with almost no rain.

”There seems to be no end,” she said, adding: “How can we live in such harsh conditions with no water, food, and farm-related jobs?”

Selling stock, seeds to survive

In a January assessment of Sindh’s eight worst-hit districts, roughly five percent of households surveyed said a family member had migrated in the last six months due to the drought. The study – by UN agencies, NGOs, and the provincial government – found food insecurity in 71 percent of households polled, and nearly one third reported severe levels of food insecurity.

In order to cope many farming households said they were resorting to “extreme irreversible strategies meant only for emergencies”, including selling off land, seed stocks, and their last female animal. The study recommended a “rapid and comprehensive” humanitarian response, as well as deeper long-term investments to improve water and agriculture infrastructure, and access to basic healthcare.

Preliminary results from a separate national nutrition survey, conducted last year, also found emergency levels of malnutrition in all eight districts. In Tharparkar, the survey found 22 percent of children under five to be moderately or severely malnourished; rates of “global acute malnutrition” higher than 10 percent generally indicate a “serious” emergency.

Dr. Nushin Hamid, the country’s parliamentary secretary for nutrition, said the drought has threatened the income of farming families, which can lead to malnutrition as food supplies run low. “There are tens of thousands of poor communities across the country that lack financial resources to protect their families from the growing risk of malnourishment, diseases, and possible deaths,” he told IRIN.

‘Forced to migrate’

The drought is also reaching other parts of the country that usually see more rainfall or benefit from better irrigation.

Allahrakhi Bibi, a farm labourer from northern Sindh’s Qambar Shahdadkot district, left her home in September and migrated to Larkana, a bustling town near the Indus River, which flows through the length of Pakistan.

She said her family relies on their only valuable possessions – four camels – to plough a plot of land for a local landlord. But, after repeated crop failures over the last two years, they had to leave.

“We felt forced to migrate with 36 other farming families when we saw our fields getting parched,” she said.

Bibi now tries to make ends meet by selling camel milk in Larkana, but it hasn’t been enough for her family of five.

Omar Mahmood Hayat, who chairs Pakistan’s National Disaster Management Authority, said farmers in the worst-hit districts are abandoning their homes to migrate to urban areas. He said authorities were focusing efforts on these rural farming communities, distributing free grain, water, and medicine to help them adapt.

Future risks

While authorities and aid groups respond to the current drought, climatologists say Pakistan can expect drought conditions to become more frequent and more intense in the coming years.

“Droughts in Pakistan were [a] very rare phenomenon and would occur once in a decade or so,” said Muhammad Riaz, a climatologist and director-general of the Pakistan Meteorological Department. But now, he said, even well-irrigated areas and other parts of Pakistan that normally see steady rains during monsoon seasons are grappling with drought conditions.

Climate change projections suggest temperatures will rise and make the seasonal monsoon rains increasingly unpredictable, raising the threat of humanitarian impacts from extreme weather.

“Spiking temperatures due to global warming in the coming years would further deepen drought severity and frequency in most parts of the country,” said Kamal Ahmed, a climate scientist at Lasbela University of Agriculture, Water and Marine Sciences in Balochistan.

For now, aid groups say there are urgent needs across the spectrum: emergency food, medical assistance, clean water, and help to support recovery for stricken agriculture and livestock. The government has asked agencies like the World Food Programme, UNICEF, and the World Health Organisation to help boost nutrition programmes, a WFP spokeswoman said.

(TOP PHOTO: A man leads his herd from drought-hit Tharparkar district in southern Pakistan in search of an irrigated area elsewhere in the province. CREDIT: Saleem Shaikh/IRIN)

ss-st/il/ag