How do humanitarian donors break through long-standing roadblocks to get funding to frontline aid groups? A celebrity-backed startup says it has an answer.

BlueCheck Ukraine is quickly vetting and funding small Ukrainian NGOs and civil society groups on the front lines of a war that has killed 10,000 people and uprooted one in five Ukrainians.

The foundation is brushing past persistent hangups that have stalled the aid sector’s localisation promises – and it’s co-founded by a team that includes a veteran humanitarian, a TV producer, and actor Liev Schreiber.

It’s sending money quickly to grassroots groups, with few strings and little paperwork. It tries to address donor compliance fears by teaming up with pro bono due diligence lawyers. And it wants organisations that receive money to choose how to spend it.

“I think we see ourselves as a champion for localised aid,” said Jason Cone, one of BlueCheck’s co-founders and formerly the executive director of Doctors Without Borders, or Médecins Sans Frontières, in the US.

“Usually… you need to spend a lot of time to prove that you're good enough to receive this money.”

Since the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, less than 1% of humanitarian donor funding has gone straight to local aid groups, UN statistics suggest. At least two thirds of the 600 aid organisations operating (and on the UN’s radar) are Ukrainian NGOs.

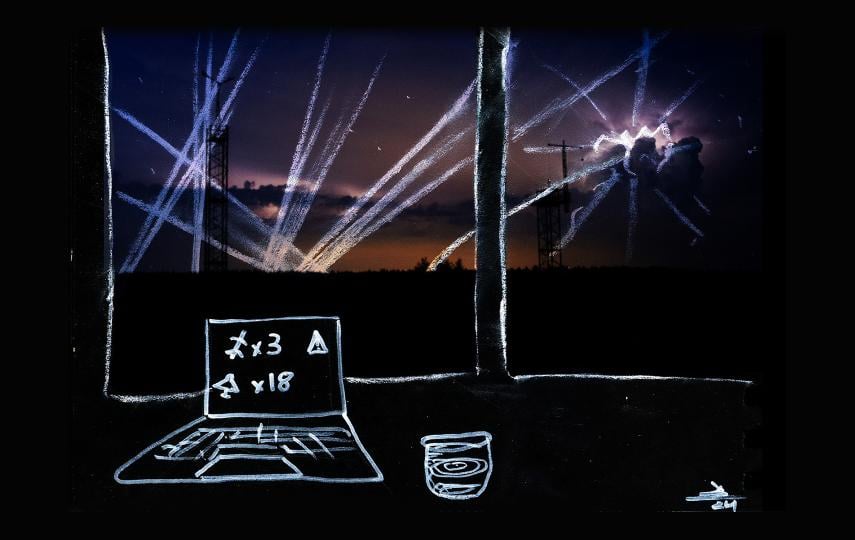

Starenki, a Kyiv-based foundation that helps elderly people, including those trapped on the front lines, received a $50,000 grant from BlueCheck after the war erupted.

The money was one thing, but CEO Varvara Tertychna said she was struck by how little time she had to spend getting it. BlueCheck, she said, handled the vetting process and demanded little from her.

“Usually, a donor is an organisation with whom you need to spend a lot of time to prove that you're good enough to receive this money,” she said.

“This is really a big difference if you are a smaller organisation, very short on staff, you're trying to do work in the field, and you are not very strong in bureaucracy.”

Finding ways to fund frontline groups – and to make aid more genuinely driven from the ground up – is increasingly urgent in Ukraine and beyond, analysts say.

Needs are spiralling, budgets are shrinking, emergencies are lasting longer, and the conventional international aid sector is overstretched.

Frontline groups are first to respond and the last to leave, but rarely receive the support the aid sector has promised over years of reform pledges. And aid is frequently delivered first by pop-up, volunteer-powered groups that need money but aren’t part of the aid machinery.

BlueCheck’s founders say its formula is working in Ukraine and could be exported elsewhere. But it’s also a question of scale: It gave $3 million last year, but the cost of global humanitarian response is in the tens of billions.

A fraction of a percentage point for local aid

By any measure, the amount of money available to local humanitarian groups in Ukraine has been a trickle.

Of the more than $6.4 billion donors gave to fund humanitarian response plans in Ukraine since February 2022, only a fraction of a percentage point – 0.71% – was sent directly to the Ukrainian NGOs and civil society groups risking their lives on the front lines, according to figures from the UN’s system for tracking humanitarian funding flows.

A portion of pooled funds – pots of donor cash meant to be more flexible – is also passed to select local NGOs. But even for a sector that has consistently failed to meet its targets to shift power and money, it’s a jarringly tiny sum.

That means little funding available for organisations like Starenki. According to a September study of localisation in Ukraine, only half of Ukrainian NGOs said they were financially stable. Many of the most precarious NGOs had less than three months of operating budget on hand. In a February survey of women-led organisations, only 12% said they had enough money to operate this year.

Tertychna said her biggest surprise receiving funding from BlueCheck was what she could do with it. Money for the overhead costs that keep NGOs afloat – staff and office expenses, for example – is a rarity in the humanitarian sector, especially for local groups that wait for funding to trickle down through middlemen UN agencies and big NGOs.

“It is almost impossible to fundraise for organisational needs, like for salaries of the staff,” Tertychna said, explaining her surprise: “When I asked if I can spend this budget for administration, like the salaries and other things there in the field, and they said, ‘Yes, just spend it the way you think it will be the most productive.’”

She used it to hire staff for what had been a largely volunteer-powered organisation.

BlueCheck’s model has been noticed by those looking for signs of change in the humanitarian system.

“You need more humanitarian-to-humanitarian ventures among the internationals to get through these roadblocks,” said Abby Stoddard, a partner with research and policy consultants Humanitarian Outcomes.

She’s not involved with BlueCheck, but calls its vetting model “an interesting idea”.

“We speak a lot about the slowness of the humanitarian sector, which is caused by a lot of these compliance regulations and accountability concerns, which are important,” Stoddard said. “But in a major emergency when it's taking three months to approve a small grant to a local organisation that is out of money and trying to do whatever they can, this is not an effective system. It's not timely and it's not what you expect for the emergency humanitarian sector.”

How it works

BlueCheck started in the days after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

A former colleague approached Cone with a question: “What can we do to help?”

BlueCheck’s co-founders have day jobs. Schreiber, who has become something of a public face for the organisation and for Ukraine advocacy in the US, knew Cone’s former colleague from grad school.

They and others in their network started thinking about what would add value in a response where big global aid groups looked set to dominate.

Ukraine didn’t need the “traditional international boots-on-the-ground” model, Cone believed. But the perception of corruption in Ukraine would likely stand in the way of donors opening their wallets for local groups, he thought, while tiny volunteer outfits were springing up and responding first, and would soon need funding to keep going.

“How could we essentially streamline that, and fasttrack funding to these smaller, more nimble grassroots organisations?” Cone said, describing the thought process.

He said BlueCheck donated about $3 million in 2023, its first full calendar year of operation.

“It's not the billions that the aid system is deploying. It's more about who we're funding and the way we're trying to put less of the burden on the people taking the risk, doing the work,” said Cone, who also oversees policy and manages grants at Robin Hood, a New York-based anti-poverty foundation.

“A lot of the organisations doing the hardest and most impactful and needful work don't have time to fill out massive amounts of paperwork.”

BlueCheck didn’t start out trying to address the aid sector’s localisation agenda – more often the realm of panel discussions, acronym-thickened reports, and glacial change, rather than fodder for CNN interviews.

But the gap in the market became clear with every email or message passed along from a Ukrainian organisation with a long list of plans but little cash to get going.

“The needs are semi-endless,” said Murphy Poindexter, another co-founder.

One organisation, Spiv Diia, had helped to build a national hotline to connect aid with people that needed it. Other recipients include groups that do landmine removal, direct cash, trauma counselling, emergency evacuations, and care for children with cerebral palsy or autism in areas where services have crashed.

BlueCheck now funds 27 groups, many of which didn’t exist before the war. Most have fewer than 25 staff and yearly budgets under $500,000.

“For localisation, one thing we’ve seen is a lot of the organisations doing the hardest and most impactful and needful work don't have time to fill out massive amounts of paperwork,” said Poindexter, who has a background in finance and startups, not humanitarian response.

“I don't know if [our grants process] is backwards from others, but we raise money, we have it in the bank, and we go to our partners and say, ‘Here's what we have. What can you do with it?’”

BlueCheck’s pre-vetting model hinges on the pro bono due diligence work provided by global law firm Ropes & Gray and Integrity Risk International, a risk consultancy.

They conduct extensive checks on BlueCheck partners, sifting through sanctions lists and media, and weighing “reputational risks” on top of the legal logjams.

“We can come in and help add that extra layer of diligence to understand who these organisations are, who these people are, if there are red flags,” said Amanda Raad, co-lead for anti-corruption and international risk at Ropes & Gray.

Raad said checks can be done in “a matter of days, in an ideal world”. For its part, BlueCheck says its fastest turnaround time from donation to bank transfer is less than two weeks.

Next steps

But there’s an obvious three-million-dollar question hanging over BlueCheck’s direct-funding model: Will it scale?

The foundation’s $3 million portfolio in 2023 is tiny compared to what the global humanitarian sector can clear.

In comparison, this year’s UN-backed response plan for Ukraine has a price tag of $3.1 billion, on top of another $1 billion for a regional refugee plan. Global response plans total $46 billion.

“I think it will only be truly helpful if it can be scaled,” Stoddard says of BlueCheck’s model. “I mean, if you can do it for 10 organisations, that's one thing. But in Ukraine, there are hundreds if not thousands of organisations that could use this.”

But if BlueCheck’s model is successful as a “proof of concept” in Ukraine, then it may be useful elsewhere, she suggested.

“I think if we're serious about localisation, there's going to have to be a change in the funding model,” she said. “It can't all be through international organisations.”

Raad of Ropes & Gray said the model is “definitely” scalable, and her firm is interested in supporting this: “I guess the question is: Is it scalable to do entirely pro bono? It does take a lot of resources.”

Cone of BlueCheck believes the model is expandable to other regions. “That's an active conversation with our board,” he said.

But the biggest stumbling block is money. As the war digs into a third year, Cone said “donor fatigue” is setting in. Like the Ukrainian groups it supports, BlueCheck, too, says it’s struggling to raise funds.

For now, Tertychna of Starenki says the support has stabilised her organisation. They’ve hired new staff, and plan to further expand in frontline areas, where needs are reaching “severe and catastrophic levels”, according to the UN.

Many Ukrainians who left as refugees are younger; many of those who stayed behind are elderly, Tertychna said.

“It is the war that made us expand,” she said, “because the point of fact is that many, many elderly are left on the front line.”

BlueCheck funding, she said, “brought the clarity in our future actions. We have the budget. We just need to work on providing help.”

Edited by Andrew Gully.