Heatwaves that are sending temperatures soaring across parts of Europe and North America are grabbing media headlines, prompting coverage of the dangers posed by extreme heat brought on by the climate crisis. But such heat in other parts of the world rarely makes international headlines, often rendering invisible the daily dangers faced by women in communities like Sikari Tola, a village in the semi-arid north-central Indian region of Bundelkhand.

Men do not usually fetch water or perform any other chores to aid in cooling during a heatwave, Ramkali, a woman in Sikari Tola, explained: “It’s all our burden.”

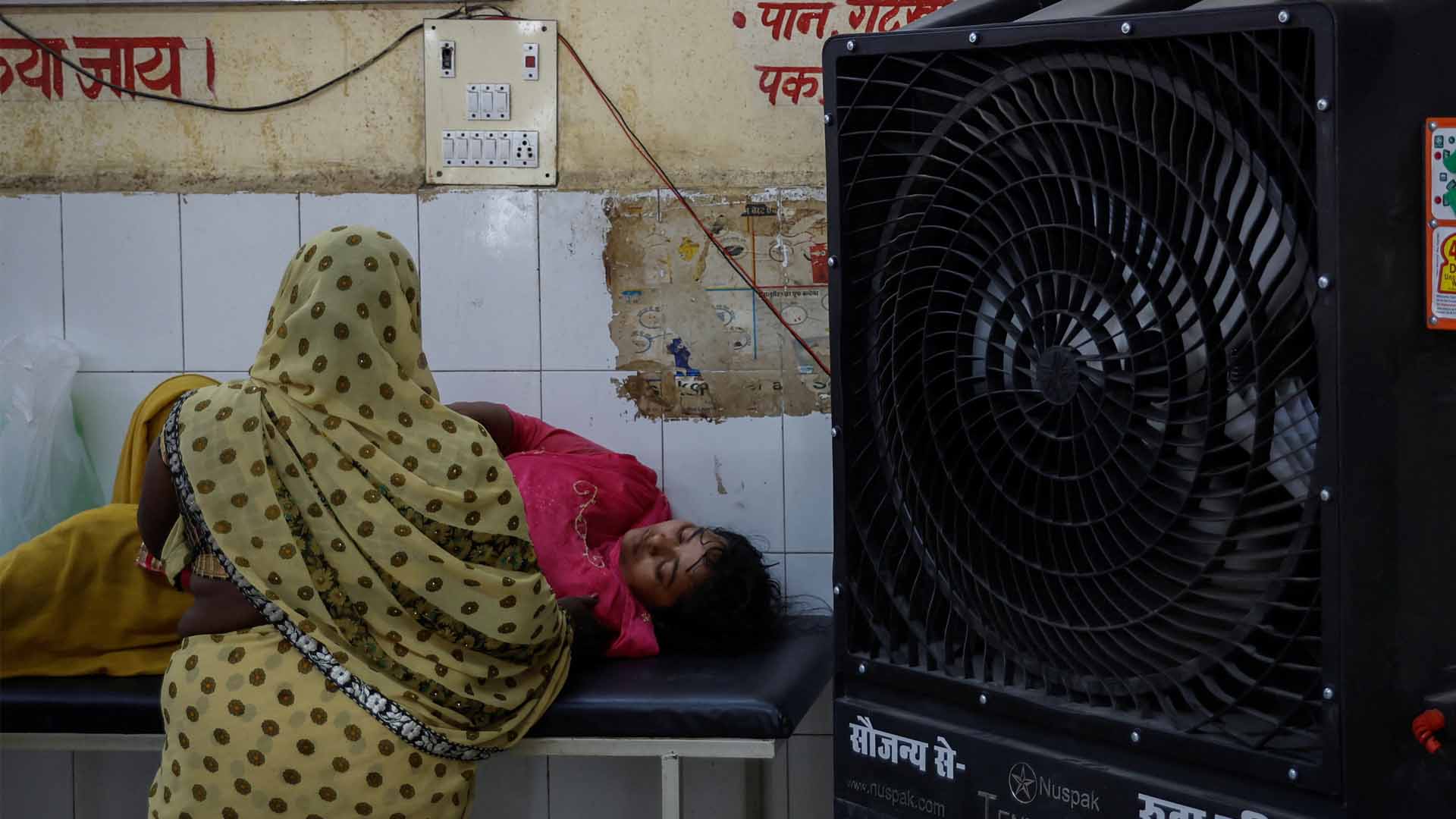

Heatwaves put an inordinate strain on India’s poorest women, who do most of the domestic work in their communities. The New Humanitarian recently spoke with women in Dalit and Adivasi Indigenous communities — where poverty is inescapable — who are responsible for providing water and other ways to cool their families.

Climate scientists predict that rising temperatures will make some parts of the globe uninhabitable. What’s surprising many of them is the speed at which temperatures are rising: Numerous heat records were broken worldwide this month alone.

Heatwaves have increased in intensity and duration in recent years across South Asia, from the Indian subcontinent to the Maldives, Bhutan, and Afghanistan. A study published by The Lancet in 2022 reported that heat-related deaths in India increased by 55% in the 17 years from 2004 to 2021.

In Sikari Tola, as the heat comes earlier in the year and is more intense, simple tasks such as fetching water become even more onerous, especially for lower-caste women — who do much of the physical labour to care for their families and must contend with low pay and discrimination in work outside the home.

Sheelkumari, in her late 40s, said the temperatures hit 35-38C as early as February this year. During a three-day visit to Sikari Tola in mid-June by The New Humanitarian, it was at least 47C every day, and highs have reached 49C.

Sheelkumari wakes early to join dozens of other village women to make the half-kilometre walk to a well to fetch water in the sweltering heat. She has to fetch more than usual, making more trips to the pump as the heat intensifies throughout the day.

Some days, she visits the well as often as 10 times.

“Getting water in this peak heat is even more difficult, especially when I am forced to make water fetching rounds in the afternoon, when the heat is highest,” Sheelkumari said. “Taking care of the domestic chores along with this makes me feel drowsy and dehydrated the whole day.”

But she has no choice.

“Even when I am unwell,” she added, “trips for water are a necessity, and I have to do it.”

Why women carry heat’s added burdens

Sheelkumari’s daily ritual is repeated by untold other Dalits and Adivasis, who are on the lowest rung of India’s traditional caste system and must often work outside despite the heat and live in homes that are difficult to cool.

An evaluation of the heat index in India found that more than 90% of the country is at risk of being adversely affected by the heat, “impacting adaptive livelihood capacity, food grains yield, vector-borne disease spread, and urban sustainability,” according to a recent study from the scientific journal PLOS Climate.

This study was published before a brutal heatwave in June was blamed for almost 100 deaths in two of India’s most populous states over several days. Temperatures of 45C, along with humidity, were recorded for several days in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar in the east, where the deaths occurred.

“Women in India are ‘doubly’ susceptible to heat because of the hours they spend out in the fields or inside poorly ventilated homes.”

Elsewhere, Phoenix, Arizona, broke a 49-year-old record for days over 43C when the 19th consecutive day was recorded on 18 July, and forecasters predicted at least another week of days in excess of 43C across the American Southwest. Chinese officials said the country had more hot days in the past six months than it has ever had, and Beijing is facing one its hottest summers on record, with temperatures over 40C for several days in mid-July.

A heatwave also descended on Europe this month, with temperatures over 40C recorded in parts of Spain, France, Greece, Croatia, and Türkiye. Temperatures reached as high as 48C in Italy, where the health ministry issued red weather alerts in 20 of the country’s 27 main cities on July 18, including Rome, Florence, and Bologna.

For Sheelkumari and other women who lug pots, jars, and pitchers to the handpump near their village, the daily struggle is all-consuming. In the scorching heat, women fill their containers quickly, taking enough to last a few hours before they have to return.

On a mid-June day while near the pump, Sheelkumari pointed to her friend, Ramkali, and laughed. “She used to be so fat when she got married and came to this village,” she said. “Now look at her with all these water Olympics every day!”

Bijal Brahmbhatt, director of the Mahila Housing Trust, a development organisation based in Gujarat, said women in India are “doubly” susceptible to heat because of the hours they spend out in the fields or inside poorly ventilated homes.

Sheelkumari and others from her village said that dominant-caste communities cut off their running water by cutting their pipes, believing that a Dalit touching a water source will pollute it.

“Even in cases where such direct violence from dominant castes doesn’t take place, women from these communities hardly have any access to water, cooling technologies, or any relief from the heatwave,” said Rihana Mansuri, a field researcher for the National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights.

Limited access to water is a daily reality for Devaki and her daughter Manju, Dalits who walk a kilometre-and-a-half daily to a local hand pump in Bira, their village in Uttar Pradesh. Manju, 12, said fetching water often makes her late to school, while her classmates from dominant castes usually arrive on time because they have a tubewell and a motor installed in their homes. Dalits are charged up to $9 a month to use the mechanised wells.

“The climate is changing across the region for everybody, but only the socially marginalised communities don’t have the resources to battle it effectively.”

Devaki, her mother, makes bindis at home, earning about $30 a month, putting the mechanically pumped water out of her reach.

According to the UN, Dalits and Adivasis form five out of every six multidimensionally poor people in India, meaning they not only lack enough income for daily needs but also do not have access to education and basic infrastructure.

In the village where Devaki lives, the houses are packed together with little to no ventilation, and it affects her productivity. She complained of constantly feeling nauseous.

“I am simply unable to make a consistent living for my daughter,” she said.

Because getting water can mean walking for a kilometre or more several times a day, some Indians in the communities visited by The New Humanitarian have started to ration their daily intake. Kavita, an agricultural labourer in Madhya Pradesh, spends many of her days drinking as little as possible, even as she feels the effects of dehydration, including dizziness and exhaustion.

For Kavita, an Indigenous Adivasi who depends on jhirias — dug up springs — for water, the daily quest for enough water is perilous.

“I used to be so scared of falling inside the pit,” she said, adding that it can take hours to dig a jhiria.

Many days, she will dig and dig only to find there is no water or that the water isn’t potable, she said.

Rajni Gautam, 25, is a Dalit member of a district development council in Jhansi in Uttar Pradesh.

“It all boils down to social mobility,” she said. “[The] climate is changing across the region for everybody, but only the socially marginalised communities don’t have the resources to battle it effectively.”

Policies to address heat often overlook the most vulnerable

Policy makers should prioritise vulnerable populations to reduce the stress from heat, Gautam said.

India’s Heat Action Plans (HAPs), the first of which was implemented in Ahmedabad in 2013, have helped avert some deaths due to heat stress. But a study by the Delhi-based Centre for Policy Research found that vulnerable groups are often overlooked. The data-based plans outline actions aimed at reducing the impacts of severe heat on communities.

Addressing gaps in the implementation of the plans is important, since South and Southeast Asia will face increasing problems related to excessive heat. Humid heatwaves are likely to recur at least once every two years if global temperatures rise by 2C, climate scientists predict. Heatwaves in India and Bangladesh are currently about 2C hotter because of human-induced climate change.

The Mahila Housing Trust has been attempting to ensure that local governments respond to the needs of women from marginalised communities. Working with the environmental advocacy group Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC-India), the trust devised Jodhpur’s first HAP with support from the municipal government.

But Abhiyant Tiwari, lead of Heat & Climate Resilience at NRDC-India, said that heat action plans have poor implementation because of the lack of funds and legal enforcement. “There’s no impetus for bureaucrats to ensure implementation because no legal body overlooks these plans,” Tiwari added.

Gautam agrees that poorer, socially marginalised communities in rural areas are being left behind as governments address the impacts of soaring temperatures through HAPs and other means.

“I wanted people of my community to get access to water,” she said. “But being in power, I could not ensure it because of lack of funding to lay more pipelines.”

Edited by Ali M. Latifi and Tom Brady.