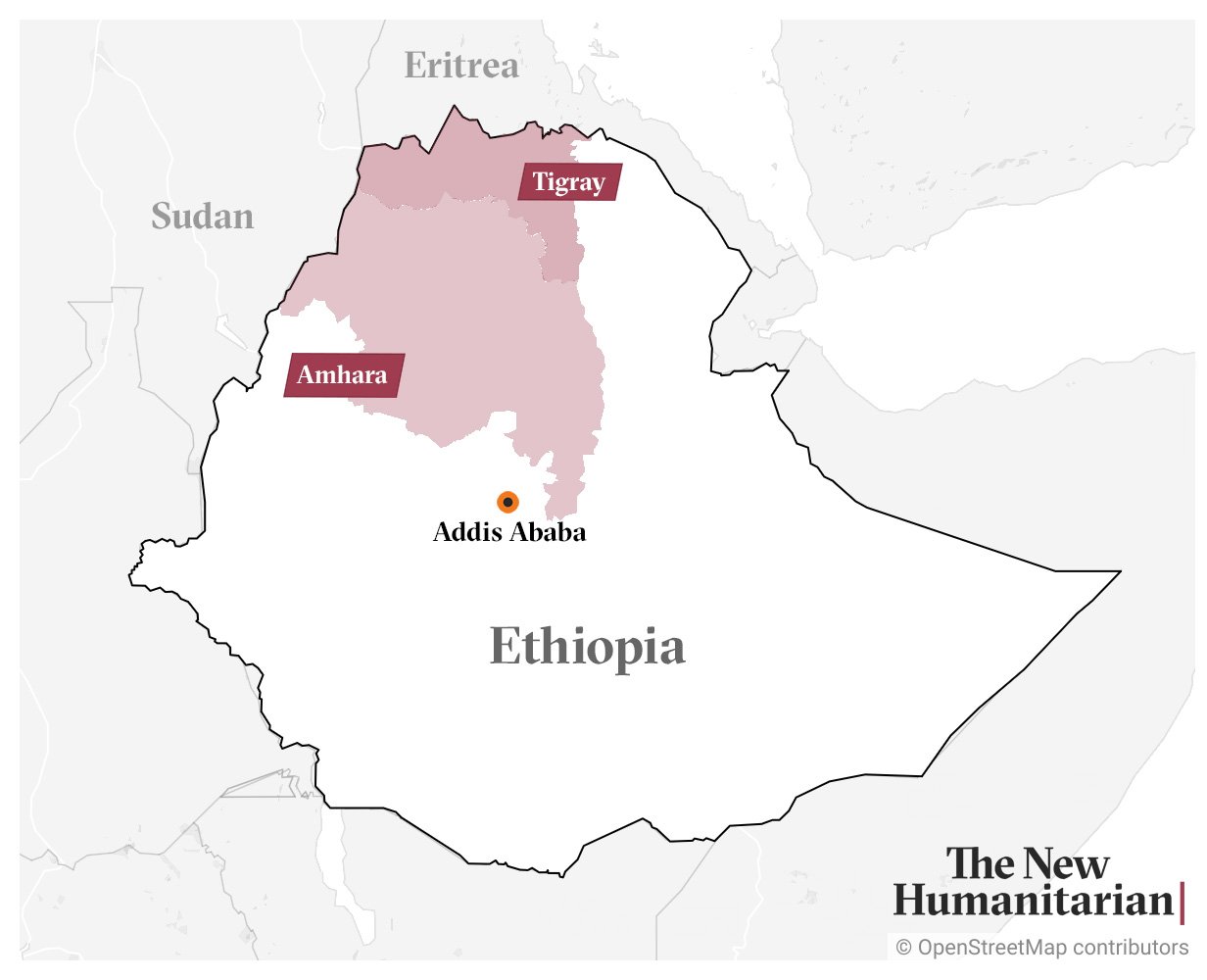

When war broke out in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region in November 2020, residents of the town of Adebay, close to the Eritrean border, woke to the sounds of gunfire and revving engines.

Eritrean soldiers were beating up civilians and forcing them onto military trucks, two witnesses told The New Humanitarian. They estimated that up to 70 people had been kidnapped that night from Heletkoka, a neighbourhood on the outskirts of Adebay.

The victims were Kunama, a small ethnolinguistic group that straddles the Ethiopian and Eritrean border. Roughly 5,000 Kunama had settled in Ethiopia in the early 2000s, fleeing land expropriation and Eritrea’s (often indefinite) military conscription.

When the 2020 Tigray war began, the Ethiopian government allowed Eritrean forces to cross the border to fight their mutual foe – the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF). But Eritrean soldiers also kidnapped Kunama refugees, forcibly returning them to Eritrea.

Fifteen people managed to escape the raid on Adebay that night, making a perilous journey on foot to eastern Sudan, settling in refugee camps around the town of Gedaref. Among them was Muna*, who identifies as Kunama.

Two years later, she is no closer to going home. In spite of a peace deal signed in November between the federal government and the TPLF to end the war, like many other refugees from minority communities, she still worries for her safety in Ethiopia.

No confidence in the peace deal

The war, fought against the TPLF by federal forces backed by Eritrean and Amhara regional allies, is estimated to have directly killed hundreds of thousands of people. Countless more have suffered the spillover effects of the two-year conflict, including a de facto blockade that left millions without adequate access to food and medicine.

Among the victims were the Kunama, Irob, Qemant, and Agew – minority groups living mainly in Ethiopia’s Tigray and Amhara regions. In a conflict characterised by information suppression, little is known about the violence these communities have experienced, and the threats they continue to face.

“After war, you want to be with your own people.”

Refugees in Sudan told The New Humanitarian they doubt they will be safe, secure, and politically represented in post-conflict Ethiopia.

Different minority communities have responded to these fears in different ways. Some are withdrawing into their own communities, agitating for greater political autonomy. Others are arming themselves or aligning with other armed groups not included in the peace deal. Some worry they can never return. All were swept up in a war not of their making.

Aida* and Fissha* are from Irob, a community of about 30,000 people living along Ethiopia’s mountainous border with Eritrea. If they do return to Ethiopia, it won’t be back to diverse towns like those they left behind in Western Tigray, a region that witnessed some of the most vicious fighting. “After war, you want to be with your own people,” said Fissha.

Before the conflict began, Aida and Fissha had moved from Irob to a small town near Dansha, in Western Tigray, in search of work. The region is officially part of Tigray, but the next-door Amhara region historically claimed it as their own.

When Amhara and federal forces arrived in the area at the start of the war, the homes of the two women were looted by Fano, an Amhara region militia. Leaflets were also scattered, warning Tigrayans they had one week to leave or they would be killed.

As Irob are culturally close to Tigrayans, Aida and Fissha believed they would be targeted too. When three of Aida’s male relatives were severely beaten up by Ethiopian soldiers, the frightened family made the difficult decision to leave Ethiopia.

Yet, if the Ethiopian government could guarantee her safety, Aida said she would return to Western Tigray. She enjoyed her job as a teacher, and had a decent life in the community. But Fissha laughed at the idea: “You will be the only Irob left in Dansha!”

Continued Eritrean occupation

No Irob refugees believe it’s safe to return to their home region. It’s one of the few areas of Tigray that still remains inaccessible to aid agencies, according to the Tigray Regional Emergency Coordination Centre, a group of international and local NGOs and regional government officials.

“Eritreans still occupy half of Irob,” said Tesfaye Awala, the chair of Irob Anina Civil Society, a diaspora-based organisation. He believes Eritrea is trying to “erase” the Irob community and establish a military buffer zone in their strategic highlands. In a rare press conference in Nairobi last week, Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki sidestepped questions regarding Eritrea’s presence in Tigray.

“You will be the only Irob left in Dansha!”

Sexual assaults by Eritrean forces have persisted in spite of the peace deal. A priest who has helped women rape survivors access local doctors told The New Humanitarian women are still fleeing Irob. Survivors have walked for days to avoid Eritrean roadblocks en route to Dawhan, Irob’s capital.

The fact the withdrawal of Eritrean forces was not explicitly mentioned in November’s peace agreement is a source of anxiety for both Irob and Kunama refugees in Sudan. They are concerned their communities still remain vulnerable to cross-border attacks and kidnappings.

“The peace deal says the Ethiopian army is supposed to protect the border,” Tesfaye, the civil society activist, told The New Humanitarian. “But how can they protect us when they collaborated with our attackers?”

Just last week, a Kunama refugee told The New Humanitarian they continue to receive reports of kidnappings by Eritrean soldiers around Sheraro. The town is close to the Shimelba camp, which hosted Kunama refugees until it was burned down in December 2020 while under the control of Eritrean forces.

Fighting for self-determination

Meanwhile, in the Amhara region, Qemant and Agew communities have also been swept up in violence related to the Tigray war. Civilians were killed and displaced by the Ethiopian army, Amhara regional forces, and Fano militia, who accused them of supporting the TPLF.

The violence during the war worsened pre-existing tensions over land, cultural identity, and political representation in Amhara. Qemant and Agew factions have now taken up arms to fight for their own “regional state”, which under Ethiopia’s constitution means they can form region-based security forces and have federal representation.

Etenesh*, a Qemant refugee in her 60s, trembled as she recounted her husband’s death during an attack by federal and regional forces on Gubay town. Fano militants killed her husband in front of her, and now occupy her home. “They cut him with knives,” she said, tears streaming down her face. She never got to bury his body.

“Ethiopia is a federation of ethnicities and everyone deserves to feel safe living in any part of the country.”

She and dozens of other Qemant refugees told The New Humanitarian they can’t return home to towns patrolled by the same security forces that attacked their communities. Violence against civilians helped galvanise support for the Qemant Liberation Army (QLA). It continues to fight to reclaim militia-occupied lands and achieve regional statehood for the Qemant, who are now believed to number over 172,000 – their population was last counted in 1994.

Agew communities in southwestern Amhara also faced attacks by Fano and Amhara security forces. Farmland was seized, and they were prevented from speaking their language, Agew rights campaigners told The New Humanitarian. These experiences helped drive support for the Agew Liberation Front (ALF), which is also seeking regional self-determination for the approximately 900,000 Agew.

“I used to believe in an Ethiopian identity,” said Mola Mekonen, an Agew activist in exile in Australia. “I now identify more as Agew.”

In late 2021, Qemant and Agew political groups publicly joined a “federalist” coalition in the diaspora led by the TPLF. The coalition included the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) and seven other organisations whose members believe that a decentralised federal system is necessary to protect Ethiopia’s ethno-linguistic diversity.

As the conflict wore on, armed members of the coalition began to collaborate in Ethiopia. The Amhara regional government sees these groups as a threat to their security.

The rise of the OLA

Under the peace agreement, the TPLF is obligated to halt support to other armed groups. As a result the QLA and ALF have lost a powerful backer. But members of the coalition told The New Humanitarian they will continue to work with other groups that support “self-determination” rights in Ethiopia.

For now, they say their best bet is the OLA, whose insurgency in Oromia isn’t covered by the peace agreement and has intensified since the deal was struck. An OLA representative, living outside Ethiopia, said joint training operations have been conducted with the ALF in Western Oromia.

But the durability of these new alliances is unclear. A Qemant refugee noted that the TPLF did little to protect the Qemant when they led Ethiopia’s federal government from 1991 to 2019, and was angry that the Qemant were excluded from the peace process.

“Ethiopia is a federation of ethnicities and everyone deserves to feel safe living in any part of the country,” said an Ethiopian researcher who requested anonymity due to fears of reprisal. “People do not feel safe, so they are trying to protect themselves.”

The peace agreement requires Ethiopia to adopt a “transitional justice” policy to tackle impunity for crimes committed. But the federal government’s accountability proposal remains vague. It has stopped a UN investigations team from accessing Ethiopia, suggesting such work could undermine domestic institutions.

Activists and refugees disagree. They say the war destroyed trust in state institutions, including the security forces, so external involvement in investigations could help establish the facts and rebuild confidence. This seems unlikely to happen. Even the TPLF, once so vocal about the need for independent investigations, now speaks much less about accountability.

Refugees have more immediate concerns. Etenesh, who watched her husband die, simply wants to return home to a safe community where his killers no longer roam the streets they used to walk together.

For now, she will remain in Sudan, alongside so many refugees affected by war but excluded from peace.

*Names have been changed to protect people’s real identities for security reasons.

Edited by Obi Anyadike.