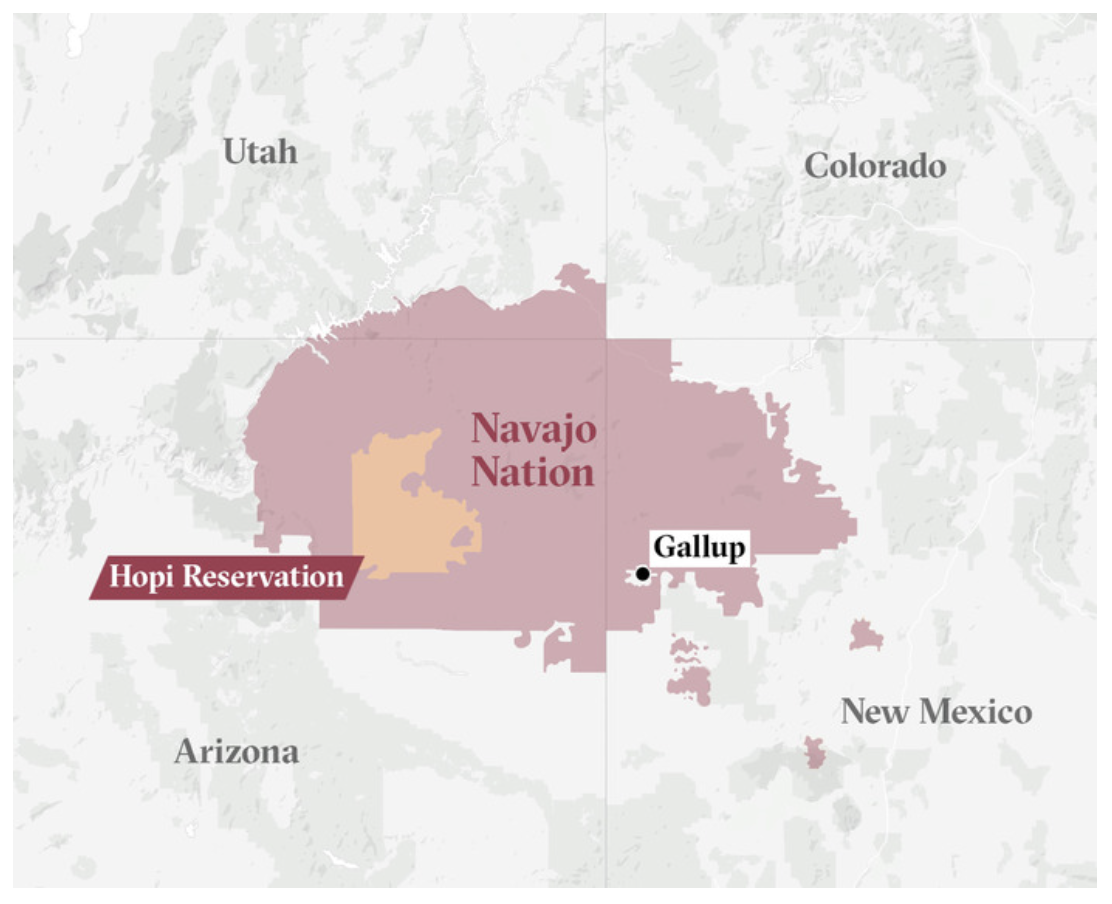

A half-hour drive south of Gallup, New Mexico, the elevation rises and the sprawling desert turns to a hilly, mint green landscape covered in piñon trees and fields of wild sage – staple plants in Navajo traditional medicine and spirituality. Unlike many Native American tribes forced to resettle permanently in different parts of the country, the reservation today lies on the tribe’s historical homeland, encompassing parts of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah.

Over centuries, the Navajo people developed a time-tested system for thriving physically and spiritually on this land. In that area today, near the community of Vanderwagen, lies Spirit Farm, a “regenerative farm” founded in 2014 with a goal to “recover and reclaim traditional farming and spiritual practices, along with modern practices, to establish resiliency in our way of life”. Among the farm’s aims is to inspire Indigenous people to grow their own food – a potential solution to persistent health disparities rooted in historical racial injustice.

Read more → ‘No one has been spared’: The climate crisis and the bleak future of food

Indigenous people in the United States have a life expectancy seven years lower than white people, and disproportionately high rates of obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. Research suggests Indigenous people were 3.3 times more likely to have died from COVID-19 than white and Asian people in the United States in the first year of the pandemic. The Navajo Nation – now the largest tribe in the United States – had a COVID-19 death rate higher than any state in the country.

A key factor affecting the disparities, many of which are diet-related, is access to healthy food. Indigenous people in the United States are twice as likely as white people to suffer from food insecurity, which can result from economic hardship as well as geography. One study found that only a quarter of people residing on tribal lands live within a mile of a grocery store, compared to almost 60% of the overall US population. The Navajo Nation – comparable in size to West Virginia – has no more than 15 grocery stores. Many people have to drive hours to reach one.

Spirit Farm is one of many nonprofits and advocacy groups combating food insecurity and health concerns by promoting locally grown produce – part of a larger project to rejuvenate and proliferate the ancient environmental knowledge that fuelled agricultural communities in North America for centuries. And now, mainstream American culture and government institutions are starting to recognise Indigenous knowledge as an asset in the face of mounting environmental challenges, reversing a long trend of suppressing it.

And this isn’t just happening in the United States. There’s a growing awareness globally of the major role industrial food production plays in the degradation of nature and climate change. Last year, the UN’s first-ever Food Systems Summit officially recognised the importance of Indigenous food systems and regenerative agriculture. But hundreds of groups from all over the world boycotted the event, many calling for a radical shift away from corporate, large-scale, monocropping agriculture in favour of smaller-scale producers like Spirit Farm.

Supported by Indigenous peoples’ success in protecting nature, Native-led environmental justice movements are gaining momentum in many countries. Recent research has shown that Indigenous peoples make up just 5% of the global population, yet they protect 25% of the land and 80% of the world's biodiversity.

‘We should not just go through the pandemic, but grow through it.’

Spirit Farm’s philosophy of connecting with nature, decolonisation, and regeneration over extraction has helped create more fertile soil and an abundance of nutritious vegetables, eggs, and meat. It offers workshops to people interested in setting up backyard gardens; six farmers currently working and learning on the premises are involved in starting their own “regenerative farms”.

“That's the thing that's really drawing people here to this farm,” said James Skeet, a Navajo tribal member who runs Spirit Farm on the eastern edge of the reservation with his wife Joyce. “We're not just talking about it, we're actually applying it.”

On the same land that he works today, Skeet recalled how his grandfather had grown crops like corn, beans, and squash for several years before destroying the ground through a more “conventional, colonised way of farming”.

James Skeet, 59, stands on Spirit Farm, which he runs with his wife Joyce. Since he started eating the nutrient-rich food they grow on the farm, he says his diabetes and arthritis haven't bothered him as much as they used to. Both he and Joyce contracted COVID-19, but recovered relatively quickly. (Luke Simmons/TNH)

Joyce Skeet explains healthy soil in front of hoop houses, which protect plants from weather extremes. Before they started Spirit Farm, both she and her husband worked for UnitedHealthcare, one of the largest US health insurers. (Luke Simmons/TNH)

As Skeet sees it, this “conventional” farming is fixated on quantity over quality. Across the United States, between an estimated 30-40% of food supply is wasted, and, globally, food production is responsible for more than a quarter of all greenhouse gas emissions. Methane-emitting livestock, long supply chains that move food products across continents or oceans, and fertilisers that leak nitrous oxide are key contributors.

For years, the Skeets have injected their plot of land with fertiliser from animals fed with fermented corn for optimal gut health. When COVID-19 came, their “closed-loop system” was barely affected at all; the breakdown of supply chains was also inconsequential for them, and they never wanted for food. The produce they grow goes to themselves or neighbours, and they hope the knowledge they’re cultivating will also spread.

Skeet said interest in the farm surged during the pandemic and their “website hits exploded”, something he sees as part of a larger trend towards recognition and value for Indigenous knowledge. While accepting that these communities are still marginalised, he thinks that “the pendulum is starting to swing back towards this Indigenous regenerative intelligence, where Native people are now being heard.”

Denisa Livingston, a Navajo tribal member, public health expert, and organiser with Diné Community Advocacy Alliance (DCAA) – Diné, meaning “the people'' in the Navajo language, is used by the community to refer to themselves – has also seen a change. Livingston has worked for years with several organisations to promote Indigenous food systems in her community and elsewhere. She approached the recent COVID-19 crisis with a simple mantra: “We should not just go through the pandemic, but grow through it.”

During the pandemic, Livingston said DCAA collaborated with other Indigenous food advocacy groups to distribute “thousands of packets of seeds” to people. In the months following, she noticed more Navajo people growing food for their families and community members, and during 2021’s harvest season there was a blooming of farmers markets and diverse locally grown foods available in the community: beans, melons, radishes, edible flowers, chillies, marigolds – “veggies that normally we would not see”.

“It was such a beautiful thing,” she said.

Livingston’s work fights the health disparities on the Navajo Nation exposed by the pandemic. “Every Diné family is affected by food-related diseases,” she said. Nearly 15% of Indigenous adults in the United States suffer from diabetes, double that of white people.

Livingston also sees progress in a broader sense: more conversations about healing Native communities “in all aspects of who we are”. She wants elders to feel comfortable sharing their invaluable cultural and environmental knowledge with the community at large.

“Much of the knowledge that we are exploring cannot be found in textbooks, cannot be found in research, but yet it can be found in trust. It can be found in relationship-building,” she said. “It can be found in creating these, not just safe spaces, but brave spaces where truth can be shared.”

The historic abuse and neglect of Indigenous peoples – which continues within some segments of the country – leaves scars. That history figures prominently in both Skeet’s and Livingston’s work. “This land is full of spoils, broken covenants, treaties that were just messed up,” Skeet said.

In the 1860s, the US military removed the Navajo from their homeland, a large rhombus marked by the tribe’s four sacred mountains. They were forced to walk more than 300 miles to a camp at Bosque Redondo, where, Skeet said, “we ate our moccasins and coffee grounds to survive.”

By 1868, when the Navajo people negotiated a return to their homeland, it had been decimated by scorched-earth military tactics, their farmlands destroyed. Their link to their ancient source of home-grown healthy foods was shattered. According to Livingston, they survived on what they could find: frybread and government rations of processed meats, then later candy, chips, and soda.

She helped create a Navajo word for junk food, Ch’iyáán Bizhool, to refer to “the scraps, the oppressive food, the prison food, the non-nutritious food, the contaminated food,” she said.

“That describes all of the ugliness,” she added.

Restoring Indigenous food systems can help provide people with food choices much healthier than Ch’iyáán Bizhool. In line with this idea, Skeet defines poverty as “a lack of alternatives”, and said the farm is about trying to “create alternatives”. While he sees colonisation as fostering dependency, he’s focused on autonomy – demonstrating how people can grow their own food without needing to make an overwhelming financial investment.

In 2014, Livingston and other members of DCAA successfully lobbied the Navajo tribal government to pass the Healthy Diné Nation Act, which imposed a 2% tax on junk food – the first law of its kind in the country. That tax raised over $7 million in its first four years, most of which has gone towards community wellness programmes on the reservation.

“It has been a slow progress to get to where we are now, and I'm really excited to see that there are now many more opportunities,” she said. “People realise that they are a change-maker, and that they can create change within their families or their villages.”

A shifting culture

Prior to COVID-19, contemporary Indigenous stories and voices were largely absent from media, education, and entertainment in the United States, according to a 2018 report. But there’s a sense that the pandemic’s highlighting of health disparities, along with the country’s two years of intense reckoning with racial injustice, could usher in a new era of awareness for Native Americans. FX, NBC, Netflix, and Martin Scorsese are all actively producing projects telling Indigenous-centred stories with Native creators.

“All of this is going to show a lot of impact in the coming years,” said Erik Stegman, CEO of Native Americans in Philanthropy. “We're going to have more and more young people who are actually learning about Native people instead of learning about Native stereotypes.”

This shift in popular culture is echoed in the very institutions once dedicated to squashing Indigenous voices.

In November 2021, the White House released an official memo declaring that Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge (ITEK) “can and should inform” US federal policy. It includes examples of how the federal government is already harnessing ITEK in collaboration with Indigenous people. Wabanaki Indians in Maine are working with the National Park Service on research demonstrating their ancient method of sustainably harvesting sweetgrass. Meanwhile, Cowlitz Indians in Washington are working with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to map historical distributions of threatened eulachon fish based on oral tradition.

“It’s a beautiful memo,” said Michael Kotutwa Johnson, an extension specialist at the University of Arizona’s School of Natural Resources and the Environment who is also a traditional farmer on the Hopi reservation.

But although Johnson is encouraged by the federal government’s recent stance, he said there’s still progress to be made. Indigenous farmers sometimes don’t qualify for funding because their methods aren’t considered “scientifically proven”, he explained. A 2021 study – which Johnson authored with colleagues from the University of Arizona – found that while Indigenous people work 6% of the country’s farmland, in 2017 they were awarded a disproportionately low number of contracts by two major federal government programmes focused on environmentally friendly agriculture. Nearly 40% more contracts would need to be awarded to Indigenous farmers to make their participation proportionate.

Like his grandfather before him, Johnson farms on land wholly contained within the Navajo reservation in Northern Arizona. Dryland farmers like Johnson, in the high-elevation Hopi desert, grow their heritage corn – sometimes blue, deep purple, and white in colour – with little rainfall and no irrigation from canals. Some of the Hopi dryland farmer’s key methods developed, Johnson said, over 3,000 years of trial and error, and include vegetative strips surrounding fields that block wind, and wide spaces between crops to maintain soil moisture.

Animals play an important role at Spirit Farm. They are nourished by probiotic-rich, fermented feed and produce nutritious eggs and meat, as well as manure that fertilises the soil. It’s all a part of what they call a “closed-loop” system. (Luke Simmons/TNH)

“[Indigenous people] live in these beautiful areas that are very biodiverse. We know how to use the plants, what the soils can hold, when to plant,” Johnson said. “It's all that stuff you learn by living in a location for a long, long, long time.”

Johnson has long straddled the line between the worlds of traditional Indigenous knowledge and Western scientific knowledge safeguarded by elite universities and valued by powerful government entities. When he attended Cornell University in the 1990s – before later earning a PhD from the University of Arizona – he said he was told it took at least 33 inches of rainfall to grow corn. “I kind of smiled at them and said that's not true,” he recalled: Johnson knew that on the Hopi reservation they grow corn with as little as six inches of rainfall.

The Native American Agriculture Fund outlined a $3.4 billion plan to support Native food and agriculture, which, Johnson said, depends on uncertain funding. He also mentioned efforts by the Intertribal Agriculture Council to develop an official “Rege[N]ation” seal that could go on certified food products from Indigenous farms committed to sustainability and the renewal of ancient wisdom, such as Skeet’s Spirit Farm.

Though Johnson is wary of Indigenous food systems being exploited and marketed for profit, he said the idea of collaboration is important. “That means that you're sharing with [Indigenous people] your knowledge, you're not just taking something,” he said.

With financial support from the government to bolster Indigenous farms’ operations and a growing appreciation for Native wisdom from the public, it’s easy to imagine a growing market for Indigenous-grown food that is healthy for people and the planet.

“Can you imagine Native Americans leading the United States’ agricultural quality production? To me, that's important. I could see that happening,” Johnson said.

‘This systematic racism comes from the ground’

Spurred by the pandemic, an influx of money for Indigenous-led organisations is going toward basic necessities and closing the education, wealth, and health gaps the virus exposed. But if it is sustained, it could also accelerate the proliferation of the Indigenous knowledge that developed over thousands of years.

At the heart of Skeet’s Spirit Farm mission is combating an industrial, Western mindset he sees as based on urbanisation, extraction, and fostering dependency, and replacing it with an Indigenous one based on a deep connection with – and knowledge of – nature. In Skeet’s mind, this change starts with the foundation itself, as exploitation begins with the soil and permeates to other parts of society. “This systematic racism comes from the ground,” he said. “Social justice? No, it's soil justice.”

The Skeets are working with researchers to study the plant-feeding and water-retaining organisms in their own soil: fungi, nematodes, protozoa, and arthropods. Supported by a grant from the Robert Woods Johnson Foundation, Spirit Farm conducted a study to measure the microbial contents of their soil and nutrient density of the vegetables it produced. As they applied their “Indigenous regenerative knowledge” – adding compost, shading, and windbreaks to their garden – the beneficial fungi in the soil increased. They found that vegetables grown in theirs and other gardens using similar techniques had nutrient densities greater than 80% of certified organic vegetables and 100% of the conventionally grown, grocery-store bought vegetables they tested.

Young plants in the hoop house at Spirit Farm, which combines modern and traditional agricultural practices. The Skeets collaborate with researchers and advocates from across the country to scientifically study their work and promote the idea that equitable food systems are essential for social justice. (Luke Simmons/TNH)

A seedling sprouts from the Spirit Farm soil, which James Skeet describes as rich “like chocolate cake”. Studies conducted at Spirit Farm show that their regenerative practices result in more beneficial fungi in the soil and more nutritious vegetables coming out of it. (Luke Simmons/TNH)

As they continue to fine-tune and study their techniques, interest in what they are doing continues to grow. Near the Skeets’ large rainwater reservoir is a guest trailer, which has been occupied by a steady stream of visitors from near and far since the pandemic began, including farmers, scientists, social justice activists, and academics.

The gap between Western institutions and traditional Indigenous knowledge closes a little with every visitor.

“That's what gives me hope,” Skeet said. “We're all going to work together, we're all going to get connected with the earth and the sky, and we all can say we did what we needed to do to make things right.”

Edited by Helen Morgan.