In the sparsely populated highlands of the Andes Plateau, alpaca herders like Florencio Vargas Hancco are starting to see the impact of frequent droughts and harsh winters on their lives and livelihoods.

“It’s all dry. There’s no grass,” said 30-year-old Vargas Hancco, looking over the parched hills surrounding Tarucani, a small village located 4,400 metres above sea level. “The alpacas are thin because they have nothing to eat.”

Drought has decimated the vegetation in the vast Altiplano flatlands, which are tinged in hues of burnt brown, broken in the east by snow-covered peaks at the border with Bolivia. Like elsewhere in Peru’s Andes, nearby glaciers are receding at alarming rates, and are expected to disappear over the next 15 years.

In 2021, the latest severe drought left parts of the Andes with little or no snow. When Vargas Hancco spoke to The New Humanitarian in October, he said his animals were leaner than ever, and that he was unable to sell them at market prices

“We don’t have enough income to support our families and our children,” he said, worried his children might not be able to continue their studies once they complete mandatory education – opportunities that most parents in this village never had.

Disaster risk experts say understanding increasingly volatile climate patterns and weather forecasts in the Andes would help residents like Vargas Hancco adapt to hazards, and enable local authorities to better respond to their needs. But this kind of data is frequently unavailable in Peru and many countries hit hardest by the climate crisis.

Localised data can help governments project climate forecasts, prepare for disasters as early as possible, and create long-term policies for adapting to climate change.

Wealthier countries tend to have better access to new technology that allows for more accurate predictions, such as networks of temperature, wind, and atmospheric pressure sensors.

But roughly half the world’s countries do not have multi-hazard early warning systems, according to the UN’s World Meteorological Organization. Some 60 percent lack basic water information services designed to gather and analyse data on surface, ground, and atmospheric water, which could help reduce flooding and better manage water. Some 43 percent do not communicate or interact adequately with other countries to share potentially life-saving information.

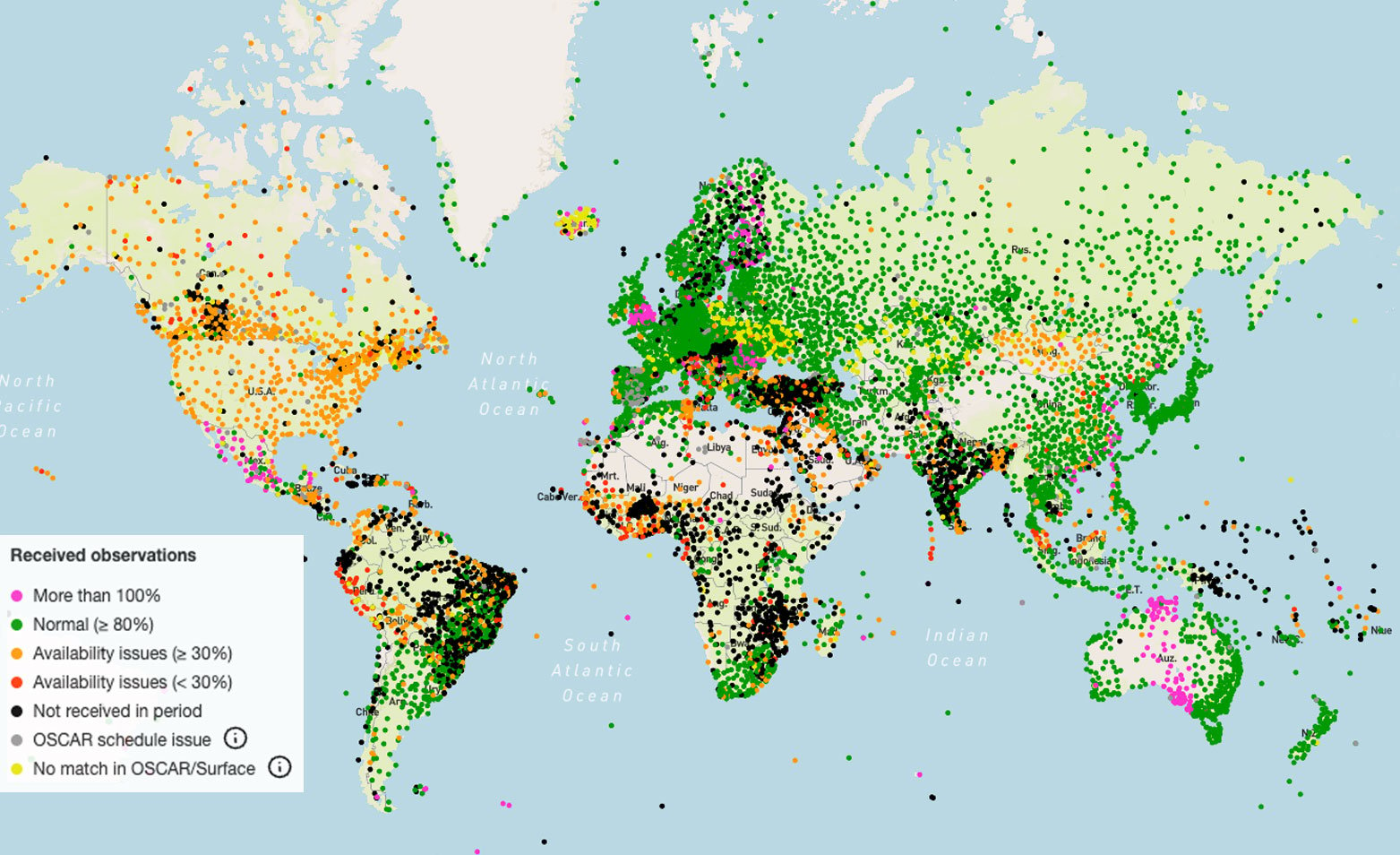

The black holes in weather data around the globe

See WIGOS's full interactive map

“Right now, we can analyse weather; in other words, what happens today, tomorrow, and the day after,” said Ena Jaimes Espinoza, a weather expert at CENEPRED, Peru’s national centre for disaster monitoring, prevention, and risk reduction. “For climate data, where you need years of data, there is still a dearth [of information].”

Without this information, she said, it’s difficult to establish accurate trends in different areas of the country – trends that could help forecasters better predict conditions in Tarucani, for example, or help policymakers to plan responses.

Inadequate funding, poor data-sharing between countries, and conflict, at least in some parts of the world, contribute to the data shortfalls. Climate experts warn that some of the world’s most disaster-vulnerable countries risk being left behind as this information gap widens.

Junk data

There are countless examples where data scarcity can cost lives.

In 2019, Cyclone Idai – one of the deadliest storms to hit the southern hemisphere – left hundreds dead and millions in need of humanitarian assistance across Mozambique, Malawi, and Zimbabwe. While Mozambique had the capabilities to predict rainfall, the government was unable to forecast the full impact of the event, which left 2.2 million people in need of urgent assistance.

Meanwhile, Malawi lacked the capability to predict Idai at all, Petteri Taalas, the WMO’s secretary-general, said at a press conference ahead of the COP26 climate summit last November. This led to nearly one million people – 5.4 percent of the population – being affected by flooding that caused some $220 million in damage.

“The lack of basic observations is having an impact on the quality of early warning services,” Taalas said.

“If you put junk into forecast models, you will get junk,” he added, stressing that accurate data is key to making better predictions that may save lives.

One of the reasons for scarce data is a lack of investment. Another is ongoing conflicts. Both of these factors have contributed to a 50 percent decrease in data gathered from weather balloons across Africa between 2015 and 2020, according to the WMO.

“Developing countries do not have the resources to invest in disaster-resilient infrastructure, multi-hazard warning systems, or risk modelling,” said Mami Mizutori, the head of the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, speaking at the September launch of a report tallying 50 years of global disaster deaths and damages.

The COVID-19 pandemic also dealt a blow to data collection.

In Peru, Ena Jaimes Espinoza of CENEPRED said COVID-19 affected data collection, particularly in isolated regions: “Due to the lockdown, lots of data from many places was not possible because weather stations are generally located very far [away].”

There are newer weather stations with automated data collection coming online in Peru. But generally, the country still relies heavily on “conventional” stations, where researchers must retrieve or observe data in person.

The WMO said lost weather observations impacted the delivery of quality early warning services in many developing countries during the pandemic.

Measuring global heating

Obtaining accurate meteorological data is also important for forecasting climate heating on a global scale, especially given recent evidence that some countries’ self-reported emissions calculations may not add up.

In November, at the next UN climate summit in Egypt, signatories to the Paris climate agreement will be expected to ratchet up or adapt their carbon-cutting commitments to limit global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Accurate data is crucial: If the data is imprecise, countries may not get an accurate picture of their progress, or the changes they need to make.

Even the UN’s landmark reports on climate science would benefit from better data. This week, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the scientific body that reports regularly on the state of the global climate, released its highly anticipated report underscoring that the humanitarian impacts of climate change are already well underway. IPCC reports are essentially a compendium of what the world’s top scientists know about climate change. But previous reports also note where datasets were limited or insufficient – most notably in Africa and Latin America.

“It means that IPCC scenarios are on a poor foundation,” said Lars Peter Riishojgaard, director of WMO’s Integrated Global Observing System (WIGOS), which aims to improve data collection and cooperation between countries.

More complete data could help climate scientists make more definitive predictions. But right now, the capabilities to obtain that valuable data are overwhelmingly concentrated in high-income countries. While well-resourced jurisdictions may draw from observations made multiple times in a single day, others must rely heavily on historical data in the absence of better options.

“We basically do not know the current climate [of many African countries], because we use the same observations averaged over 30 years to define what the climate is,” Riishojgaard said.

Data as a global good

Efforts are underway to bridge the data gap.

The Systematic Observations Financing Facility (SOFF), unveiled in November and backed by UN agencies including the WMO, aims to support 75 developing countries to improve weather observations.

Technology transfer to the so-called Global South is often built on unequal relationships, with loans leaving poorer countries indebted to wealthier ones, said Markus Repnik, SOFF’s director. SOFF will prioritise financing models built on more equal relationships, he added.

“There’s a lot of export-driven interest because there are just a few countries producing the hardware,” Repnik said. “It is wasting a lot of money and creating unequal relationships, with rich brother giving poor brother some gifts.”

Expected to launch in July, SOFF has already received donation pledges from Scandinavian governments as well as Portugal and Austria.

While the US government has not committed to SOFF, it has supported improvements to hurricane forecasting in the Caribbean. Other bilateral pacts exist, such as one between Swiss and Peruvian weather authorities to improve resilience in Andean agricultural communities, including the Puno region, where nearly half the population lives below the poverty line.

In October, after four years of talks, WMO’s members agreed to exchange available weather and climate data.

While these initiatives are focused on meteorological data, risk management experts such as Erin Hughey, director of global operations at Pacific Disaster Center, a US-based research group, say environmental data alone is not enough.

To make good climate decisions at the local or individual level, it is also important to note the economic impacts of disasters, such as the Andean alpaca herders’ lost livelihoods, or community responses, such as building gutters on houses ahead of hurricanes, Hughey said.

“What we are really interested in is the impact [of climate] on human society, and how society effectively adapts, so that we can both reduce climate change, but also increase resilience,” she said.

Documenting needs at food banks or community clinics amid a changing environment may help “contextualise” other weather data, she said.

“The understanding of the severity of the situation should be broader than just a warming climate,” she said. “It is not just despair. It can be an opportunity to create more equality.”

Up in the Andes highlands, Vargas Hancco and his fellow alpaca herders are hoping their needs are recognised. Climate forecasts and risk modelling are not his priority. “You cannot guess what nature will bring, if it will be drought, snow, or hail,” he said.

But he may have a solution in mind – a crucial data point local authorities could use: “For better prevention, we need grazing land and a water reserve,” Vargas Hancco said.

Edited by Anna Lekas Miller and Irwin Loy.