Before Cyclone Winston struck Fiji in 2016, Leba Volau made sure her home was tied down: the food was packed away into plastic bags and containers, and the crops were uprooted then buried so the storm didn’t get to them first. Armed with a booming voice and a mobile phone, she warned her neighbours to get ready.

“It was I who was doing the shouting,” Volau said. “Where were the men? It was us women who were doing that. For disasters, it is women who do everything.”

Volau is part of a network of women bolstering disaster preparedness and response in rural Fiji, where the threat of tropical storms and volatile weather has communities on alert throughout much of the year.

The Women’s Weather Watch programme, run by Femlink Pacific, a women’s media organisation based in the Fijian capital, Suva, sends weather reports and preparedness advice by text messages to its network of 350 women across the country. They, in turn, spread the news throughout their often-remote communities, and feed back local conditions and needs to a regular radio show broadcast from Suva.

The women help their communities prepare for storms and drought, protect their families when disasters strike, and tell distant decision-makers about submerged villages or dwindling food stocks.

In a region battered by frequent disasters, humanitarian groups say women like Volau must play a greater role in preparing for the risks. But within their own communities, they’re often sidelined when it comes to making key decisions.

“Nobody comes and asks the women what you want or what you need. There’s nothing,” said Sarojani Gounder, a local district councillor who is also a member of the women’s network. “It’s just: get the rations, stay inside, eat, look after your children. And that’s it.”

The global humanitarian system is overstretched. In 2018, the UN asked for a record $25.2 billion to cover 33 emergencies around the world. But the funding gap continues to widen as the price tag soars.

This includes the Pacific Islands, where locals say they are often overlooked when it comes to international interest and funding for crises. The region is home to some of the world’s most disaster-vulnerable countries. Climate change is expected to increase these disaster risks as sea levels rise and weather patterns become more extreme and more intense.

What is local aid?

The global aid sector has broadly committed to an agenda to “localise” aid – putting more power in the hands of locals working on the ground where emergencies hit.

Why local aid?

The aim of of the “localisation” agenda is to improve humanitarian response by making it faster, less costly, and more in tune with the needs of the tens of millions of people who receive humanitarian aid each year. Local aid workers are closer to the ground, they have local knowledge and skills, they can often access areas that international aid groups can’t reach, and they know the needs of their own communities.

Who are local aid workers?

Local humanitarian aid includes a broad spectrum of potential on-the-ground responders to crises and disasters: local NGOs, civil society groups and leaders, indigenous peoples, local governments, faith groups, as well as people who are themselves affected by crises, including displaced people and the everyday volunteers working to help their own communities.

“We women used to stay in the kitchen”

In the hazard-prone Pacific Islands, it’s not a matter of if, but when the next disaster will strike. The southwestern Pacific averages seven tropical cyclones each storm season, which typically stretches from November to April. And here in the western dry zone of Fiji’s main island, Viti Levu, consecutive years of drought have also ransacked crops and the lifeblood sugarcane industry.

It’s a volatile mix for families who depend so acutely on the weather for their livelihoods: during cyclone season they fear the storms and too much rain; in the drier months they pray for more of it.

The area saw nearly six months without a day of rain this past year, said Fane Boseiwaqa, who works with Femlink Pacific and leads monthly meetings for about 60 women in the area.

“They need to be informed to prepare for any disaster,” Boseiwaqa said. “Women are leaders, but they do not have access to adequate information and communication.”

Frequent text message alerts, sent directly to women’s phones, provide some of that information, and Boseiwaqa’s monthly meetings reinforce the lessons.

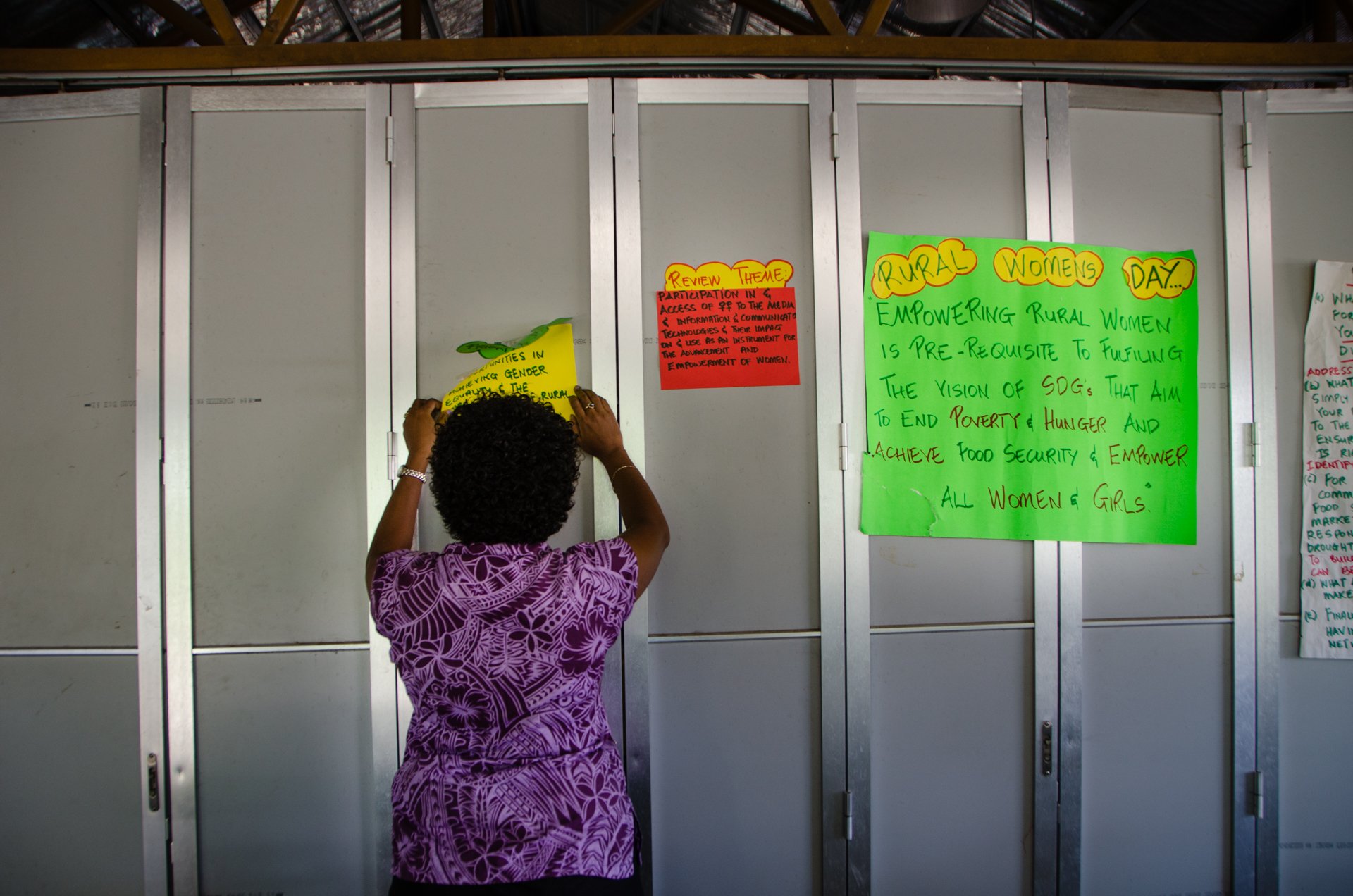

The get-togethers are part education, part community. The women discuss strategies on improving the local sugarcane industry – many run family farms hit hard by the frequent drought – or learn about international rights treaties or Fiji’s progress on gender equality.

When drought is at its worst, they trade ideas for cooking with what’s available or tips for preserving staples; when storms approach, they remind each other how to prepare: bury the crops, store the food and water in containers, tie down the house.

Each session wraps with Boseiwaqa recording a short dispatch interviewing women about their needs and concerns. The interviews are then broadcast from Femlink Pacific’s Suva studios.

For many of the women, it’s the first time they’ve ever felt heard.

“We women used to stay in the kitchen and we didn’t know how to voice up,” said Selai Adi Maitoga, a soft-spoken 49-year-old who joined the network in 2012.

“In the community, only the men speak. The men overrule everything. When we sit in meetings, we are not supposed to talk. When we raise something, they say, ‘Who are you to talk, because you’re a woman?’”

First responders

The programme is tapping into an often-overlooked resource for disaster preparedness and response: women. In rural Fiji, women run the households and make sacrifices to protect their communities – often in ways that men don’t grasp.

Consecutive years of drought and storms have shrunk crop yields and income for farming families. When food stocks run low, Maitoga said she skips meals so that her children and husband can eat. When there’s no rain and the government’s emergency water trucks don’t show up, she treks two kilometres to a shallow river to fill a bucket. Gounder said women routinely share what food they have and cook communally so that families don’t go without.

“Men don’t ask the neighbours. If they have money, they can go and buy food,” she said. “But the women, we talk to each other. That’s why women are the first responders. We do everything first.”

Women often face extra burdens and added health risks and gender violence during and after disasters, as infrastructure crumbles and they take on a larger share of household responsibilities.

After Cyclone Winston, women were essentially first responders in their communities, particularly in remote villages that were cut off from food, water, and government help for days, says Fane Boseiwaqa.

“Women were the ones going out looking for food to put food on the table for the family,” she said. “Men were trying to at least rebuild their homes again. But most of the hours have been spent by women.”

Humanitarian experts say these differing needs and burdens are often overlooked when crises hit.

The broader aid sector has also promised to “localise” humanitarian responses by helping local groups play leading roles. But these reforms aren’t always reaching local women.

Most established local organisations are led by men, and analysts say donor regulations often see money rushed to these male-led groups, rather than funding and training more women responders and leaders.

Many of the women now take the preparedness lessons they’ve learned in the programme and spread them within their own communities. Gounder, for example, said she meets with some of the women from the 465 homes in villages near her own home.

Jaimati Prasad, a 60-year-old sugarcane farmer, also brings the lessons to neighbours in her distant hillside village.

And when a disaster alert arrives on her mobile phone, Volau makes sure she’s the first to warn her village, telling local leaders how to prepare the community’s evacuation shelter.

“I told the village elders we should have access for people with disabilities too. The walkway should be accessible to disabled. Not just steps. And the toilets, there must be two or three toilets,” Volau said. “They just looked at me. Because I’ve been to many workshops and consultations. It’s an eye-opener for me. So when I go back and tell them, it is also new to them.”

“Can I survive?”

In Fiji, the bar by which all disasters are measured is still Cyclone Winston – one of the strongest tropical storms ever recorded.

Nearly everyone in Fiji has a story to tell about Winston. The February 2016 cyclone churned a destructive path across the country, wiping out a third of the Pacific Island nation’s GDP. It landed a direct hit here on the northwestern edge of Viti Levu.

Volau remembered huddling with her family in her battened-down home, shivering as the walls around her shook.

The house won’t fall, her husband had told her, before the winds made it impossible to hear anything else. But when she pointed her torch up to where the ceiling should have been, she found herself peering straight into Cyclone Winston’s fiery winds. The storm had ripped the tin sheeting off her home.

“There’s no roof! There’s no roof here!” she remembered screaming. Then the winds changed direction and the walls caved in.

Each storm season brings another round of threats and worry. A near-miss marked the start of this year’s season in early January, but Cyclone Mona still sent hundreds to evacuation centres, and subsequent downpours have triggered flash floods and landslides.

For Maitoga, each new storm warning brings memories of Cyclone Winston rushing back: hiding her children under the table, watching the waters rise, wondering if her house would collapse.

“It’s still in the minds of us women. We suffered,” she said. “But what if it happens again? What will I do? How will I survive? Can I survive? It’s a question mark you cannot answer.”

That’s why she attends the monthly meetings with a studious fervour: taking notes; asking pointed questions.

“I need to be prepared,” Maitoga said. “And now I know what to do to be prepared for the next disaster.”

(TOP PHOTO: The sugarcane industry on the western part of Fiji’s Viti Levu has shrunk after years of declining yields and increasing costs. CREDIT: Irwin Loy/IRIN)

il/ag