GiveDirectly, a leading distributor of cash aid, has suspended all its active operations in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where at least $900,000 was allegedly stolen by staff or former workers in a large-scale fraud that penetrated every department of the country office.

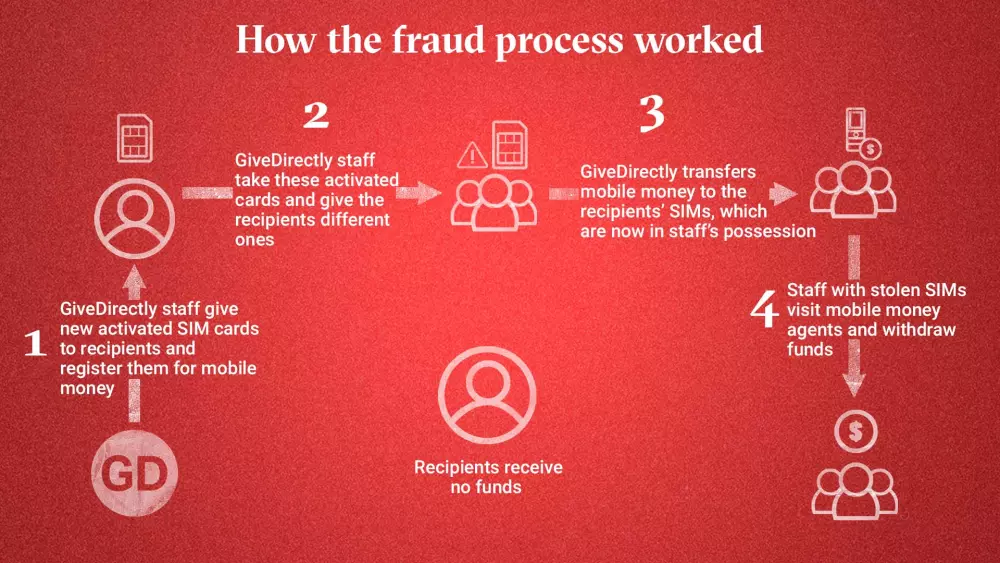

The fraud involved GiveDirectly staff stealing SIM cards that impoverished households were meant to use to receive mobile money transfers from the nonprofit organisation.

More than 1,700 families in DRC’s South Kivu province were impacted by the fraud scheme, which started in late August 2022 when the group began cash transfers there. GiveDirectly told The New Humanitarian it was the largest sum of money it has ever lost to fraud, representing nearly a third of the $2.8 million it distributed in South Kivu last year.

An estimated 5.7 million people are displaced in DRC, and there are more than 100 armed movements in the country’s east, where South Kivu is situated. The humanitarian situation has been worsened by an insurgency by the Rwanda-backed M23 rebel group.

Nearly all of GiveDirectly’s workers in DRC – roughly 75 in total working on programmes in South Kivu and Ituri province – are no longer with the organisation, mostly due to their contracts expiring. Others were terminated after disciplinary proceedings or resigned, according to GiveDirectly’s managing director, Joe Huston. Some may face prosecution.

“To the people who should have received cash, we’re sorry. It is our job to design systems that protect the funds that are supposed to reach you, and ultimately, we let you down,” Huston told The New Humanitarian in an exclusive interview on 25 May. “To our donors, I think we have a similar message: that it’s our job to deliver your funds safely.”

GiveDirectly – a New York-based NGO headed by the UK’s former secretary of state for international development, Rory Stewart – detected the fraud in January and informed The New Humanitarian in May before announcing it publicly today, saying the decision was proactive and not in response to the threat of someone exposing the case.

Although GiveDirectly voluntarily informed The New Humanitarian, reporters were unable to independently verify the scale of the fraud, how it was carried out, by whom, or the number of victims who did not receive promised funds.

“One of the devastating details of the case is that... the fraud required suppressing recipient complaints. We know hundreds of recipients called in to complain and ask about their next transfers and were told various types of lies.”

The NGO, the largest nonprofit exclusively providing cash transfers globally, works in DRC, Kenya, Liberia, Malawi, Morocco, Mozambique, Nigeria, Rwanda, Turkey, Uganda, the United States, and Yemen.

GiveDirectly said a programme audit was also underway at another of its Africa operations but declined to name which, saying only that it was "sub-Saharan", ruling out Morocco.

The NGO chose the area in DRC to assist people facing extreme poverty, malnutrition, food insecurity, and unemployment with a mixture of large grant and monthly subsistence payments.

“These were people who had high starting levels of vulnerability [who] were told that they were going to receive a potentially life changing amount of money,” Huston said.

“One of the devastating details of the case is that... the fraud required suppressing recipient complaints. We know hundreds of recipients called in to complain and ask about their next transfers and were told various types of lies,” he added.

The $900,000 fraud came out of a total of around $7 million that GiveDirectly intended to transfer to some 5,000 households in South Kivu. Households were meant to receive one-time transfers of $392, and then $40 per month for the next two years.

Although payments have been suspended in DRC since January, pending an internal investigation, GiveDirectly said it still hoped to distribute the money.

Corruption involving aid workers and public officials is common in DRC’s long-running humanitarian crisis. Perpetrators often justify it as a way of getting by in a dysfunctional state – one distorted by decades of external intervention and exploitation.

A 2020 operational review into the country’s aid sector criticised relief groups for having weak systems to detect and combat fraud. The review was commissioned after the discovery – made public in June 2020 by The New Humanitarian – of a multi-layered aid scam.

How the fraud worked

GiveDirectly provides aid in DRC through mobile money transfers, in which money is deposited to a SIM card registered to a single person’s government ID.

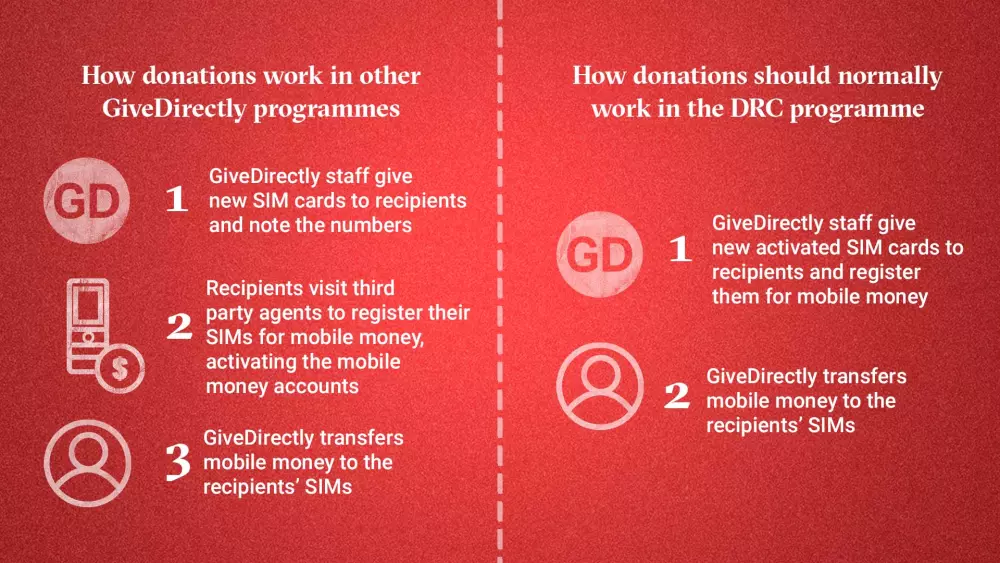

Typically, GiveDirectly gives a recipient a SIM card and they register it with an independent mobile money agent. Once the process is complete, funds go directly to the recipient’s mobile account and they then withdraw the cash at a mobile money station.

The organisation said it sees this method as reducing risk as it cuts out middlemen who would otherwise be involved in delivering money or food aid. However, GiveDirectly made an exception for the South Kivu programme.

“Normally, recipients register their SIMs with independent mobile money agents, not with our staff, but in this remote region, the closest agent is often a long distance away. We therefore allowed GiveDirectly’s enrollment team to register these new SIMs for recipients instead of sending them to agents,” GiveDirectly said in its public release.

The exception, the NGO said, was meant to spare recipients long trips to the nearest mobile money agent, which may have required them to travel through insecure areas.

The result, however, was that when GiveDirectly began sending money to the SIMs meant for poor households in South Kivu, staff who had stolen the SIM cards received the funds instead – all with the help of outside mobile money agents and former staff.

The New Humanitarian was unable to verify the specific risks or events that GiveDirectly said prompted it to loosen its protocols, inadvertently enabling the fraud.

GiveDirectly said multiple departments – the field enrollment team, internal auditors, call centre operators, and administrative staff – either participated in the fraud or covered it up once recipients began complaining that they hadn’t received any funds.

The scheme was, the organisation said, detected after a routine audit of GiveDirectly’s enrollment procedures for a separate operation in DRC’s northeastern Ituri province, where the same exception was also in place. Although the same type of SIM swap fraud was underway in the Ituri programme, payments had not yet started, so no money was actually lost there, the organisation said.

“That kicked off a broader investigation, which eventually led us to cooperate with a telecom company, who provided snippets of transaction data that let us identify specific phone numbers and shops [in South Kivu] that had been compromised,” Huston said.

The transaction data from the telecom company showed a flurry of late-night transfers from the intended recipients’ SIM cards to other mobile accounts, according to Stella Luk, GiveDirectly’s regional director for North and West Africa. She declined to name the telecom provider, citing potential prosecutions.

The withdrawal activity deviated from what recipients usually do after receiving a mobile money transfer, Luk added.

Huston said GiveDirectly’s ongoing audits in the other African country where its staff were registering SIMs for recipients have come back “relatively clean”.

“It is, of course, impossible to know perfectly how much is lost each year, but we have no reason to believe there is significant fraud not yet uncovered,” the NGO said in its public release.

GiveDirectly also said a small portion of the lost funds have been recovered, but most are likely not recoverable.

“Our hope is that people don’t learn the wrong lesson here,” Huston told The New Humanitarian. “Fraud happens everywhere, including aid and cash transfers. And it’s important to talk about it.”

The growing cash aid trend

Between 2016 and 2019, the value of cash and voucher assistance doubled from $2.8 billion to $5.6 billion, making up nearly 18% of all international humanitarian aid, according to the most recent research by the Cash and Learning Partnership (CALP) Network, which researches and promotes the use of cash assistance.

Cash assistance offers recipients more flexibility than other types of aid, and experts say it isn’t uniquely vulnerable to fraud.

“Fraud is not restricted to aid, and it’s not restricted to cash. The question for me is how, then, agencies deal with it after they uncover it.”

“I haven’t seen any compelling evidence that cash assistance schemes are at a higher risk of fraud than any other form of assistance,” Oliver May, former head of counter-fraud for Oxfam and current leader of Deloitte Australia’s international development practice, told The New Humanitarian.

Huston said GiveDirectly has informed its institutional donors of the fraud and intends to resume cash transfers in DRC after an internal investigation is complete.

GiveDirectly, which has been delivering cash to people living in poverty since 2009, has touted the advantages of direct cash transfers as a more efficient alternative to other forms of aid that restrict how recipients can use it.

Last year, GiveDirectly distributed nearly $147 million to 326,000 recipients around the world. This includes $8.8 million delivered to 55,000 people in DRC, where 26.4 million people – over a quarter of the population – are food insecure.

Though aid diversion reports tend to focus on local fraud networks operating within humanitarian agencies, civil society groups often criticise the large amounts of money spent on the salaries and living conditions of expatriate staff, and on other overheads.

“[Fraud] is not restricted to aid, and it’s not restricted to cash,” said Karen Peachey, director of the CALP Network. “The question for me is how, then, agencies deal with it [after they uncover it].”

GiveDirectly told The New Humanitarian it is in the process of commissioning an independent review of its “risk-related processes”, policies, and implementation. It has also promised a more in-depth internal review.

Additional reporting from Abidjan by Philip Kleinfeld, and from London by Paisley Dodds, who also edited the story.