On 6 May, the Israeli military issued evacuation orders affecting around 100,000 people in eastern Rafah, ramping up fears that it would soon begin its long threatened, full-scale invasion of the southernmost city in the Gaza Strip.

Rafah has been hosting somewhere between 1.3 and 1.5 million Palestinians, around 80% of whom have been forcibly displaced from other parts of Gaza by Israel’s seven-month military campaign. The city is the only major population centre that has not been almost entirely laid to waste by Israeli bombardment.

“If the Israeli military operation continues, the last remaining city in Gaza that has not been destroyed will be destroyed,” said Sam Rose, director of planning for the UN’s agency for Palestine refugees (UNRWA).

The New Humanitarian spoke with Rose, who is currently in Rafah, on 7 May about the impact of the evacuation orders and escalating Israeli attacks on people in the city. We also asked him about the ability of humanitarian organisations to continue to respond to needs if Israel launches a full-scale assault. “Everyone will have lost everything if this goes ahead, and there’s very little we can do as a humanitarian community,” he said.

Rafah is a critical entry point for the limited amount of aid that Israel has allowed into Gaza. It is also the main base of operations for humanitarian organisations attempting to respond to the population’s staggering level of need, which has been caused by more than half a year of near-total siege and one of the most destructive military campaigns in recent history.

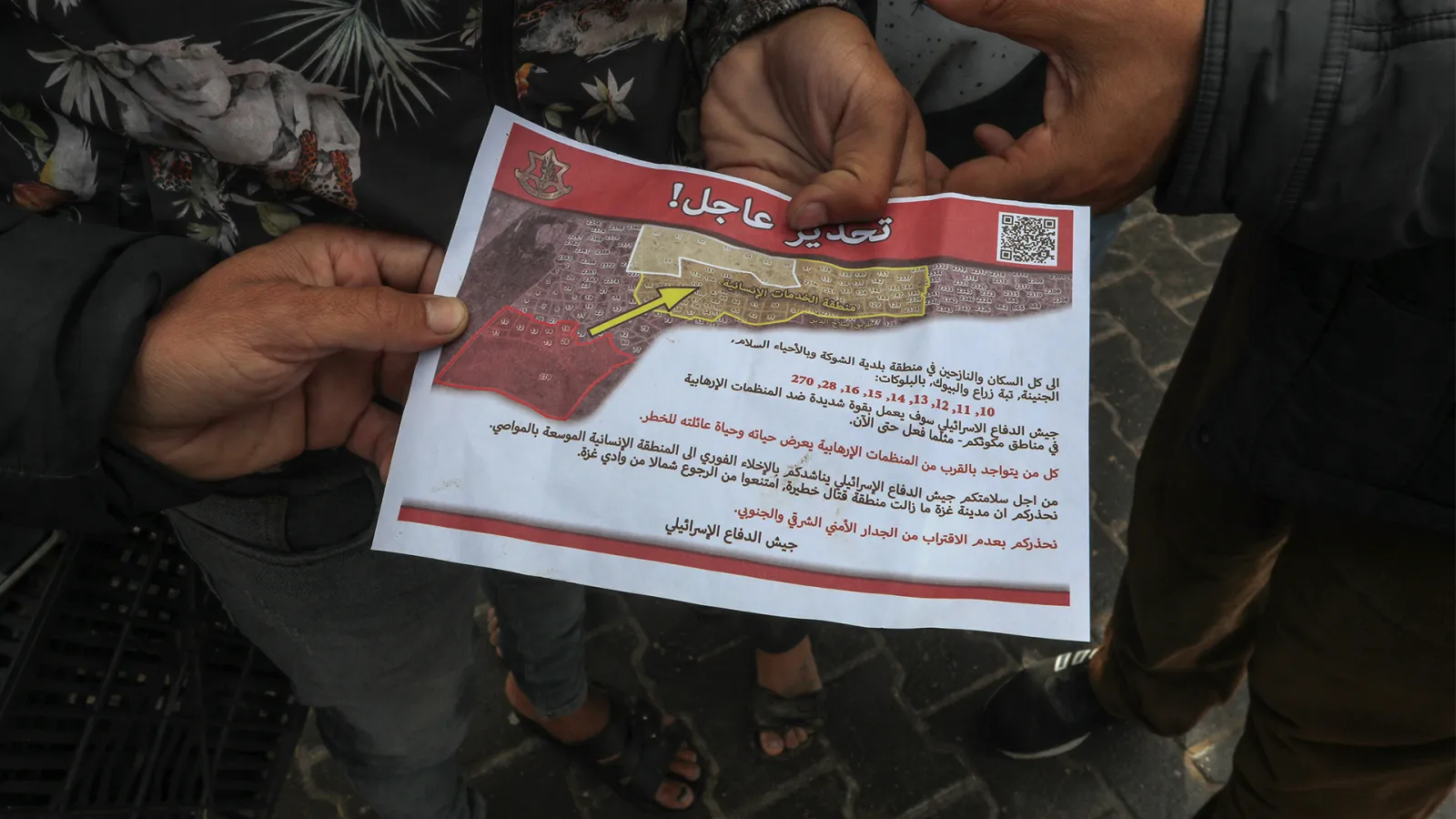

Left: The Israeli army dropped fliers on eastern Rafah warning Palestinians to evacuate on 6 May 2024.(Abed Rahim Khatib/Anadolu)

World leaders and aid organisations have repeatedly warned that an Israeli invasion of Rafah would have catastrophic humanitarian consequences and likely violate international law. As Israel and Hamas continue to negotiate over the terms of a potential temporary ceasefire deal, it’s still unclear whether the current escalation is the beginning of a full-scale invasion of the city or a more limited operation.

One thing, however, is abundantly clear: “The population [of Gaza] is on life support, and that life support is failing,” Rose said.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The New Humanitarian: What is the situation like on the ground in Rafah right now?

Rose: We’re in the western Rafah. It’s tense. It’s nervous. It’s loud. It’s always loud in Gaza, but over the past week or so – and over the past couple of days – there are just more intense bombardments a couple of miles away in the east. You can hear them here. There’s lots of overflights. There’s the constant drones that are humming in the air. And there’s also the naval shells coming from the sea. The intensity of the bombardments have really stepped up over the past couple of days.

There are a lot of people on the move. We’re a couple miles west of the evacuation zone. But Rafah is one big IDP camp. There are five times as many displaced people as there are residents, and a lot of people are living in tents, wooden structures, or makeshift structures. Many are packing up, and they’re leaving. There’s a lot of tension. There’s a lot of movement. People are extremely concerned about what’s coming.

The New Humanitarian: How are the Israeli evacuation orders affecting people?

Rose: About 100,000 people are within the evacuation zone itself. Many of them are residents of Rafah. We’re typically seeing people who’ve already been displaced being the first ones to move. We understand that many of the others are making plans to move, but most of the movement is from people already displaced within that area. People are packing up their tents and their wooden structures and they’re leaving.

We're also seeing outside of the evacuation area people who are deciding to move. They have very little. They’ve been struggling to survive in tents anyway. It’s relatively easy for people to pack up and move somewhere else. And they’re moving because they fear what’s coming. They think it might be worse if they wait to leave until it’s too late. The IDP camp outside my window has probably thinned out by about 30 to 40% compared to what it was two days ago.

The third impact is that, even though the evacuation area only affects 100,000 people out of a total population of 1.5 million, there are key services within those areas that serve people outside of them. A few of the functioning hospitals that remain, some of the general healthcare, and some of the water services people depend on are located within those areas.

What's made the situation exponentially worse has been the closure of the border crossings. Israel is now in control of the Palestinian side of Kerem Shalom. But since Sunday we’ve seen no goods coming in and we’ve seen no fuel coming in. [Kerem Shalom has since reopened. Whether it will remain open if a full-scale invasion goes ahead is unclear.].

Gaza was already on the verge of famine. Kerem Shalom was the main entry point for around 90% of all goods coming in. If that lifeline is cut off, you know, we were already failing to get on top of the famine situation before this. So, the situation will get catastrophically worse.

I want to emphasise the fuel situation as well: We’ve got half a day’s worth of fuel supplies left inside Gaza for operations. So, if the fuel is cut off for any sustained period of time, movement becomes very difficult. Powering water wells and the desalination plants becomes very difficult. Everything essentially grinds to a halt. There’s real, real concern about the fuel supply now as well.

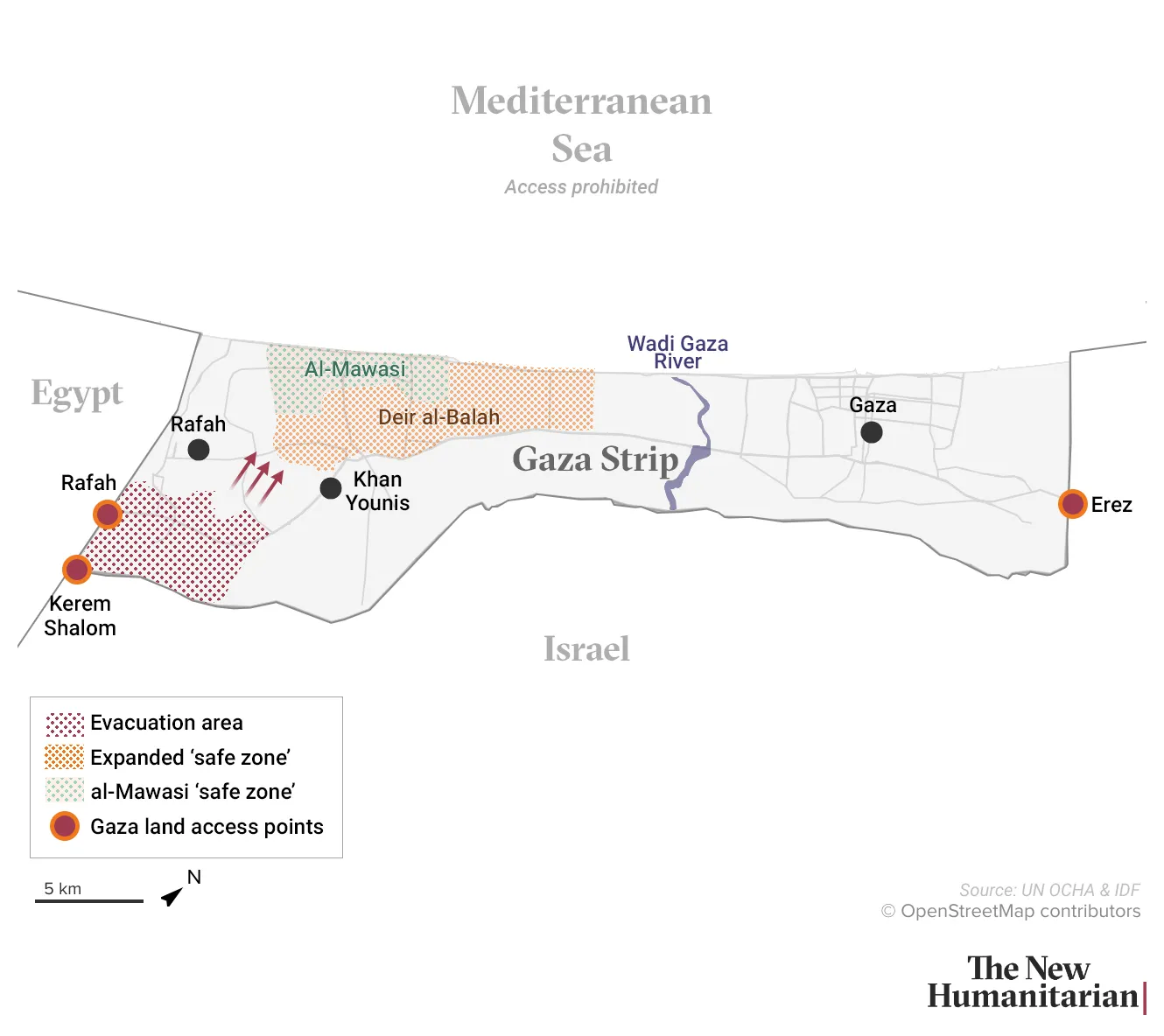

The New Humanitarian: Before we discuss the border crossings more, where are people evacuating to? What are conditions like there? And does this amount to the ‘credible plan’ to protect civilians the US has called for as a pre-condition for an invasion of Rafah?

Rose: There is no way that you can plan for something like this in a humane way – in a way that's going to meet the basic standards that we require to deliver lifesaving assistance – for a number of reasons.

One, the space that's available is very, very minimal, and parts of the area that we've been led to believe previously were in this safe zone – the Rafah part of al-Mawasi – are outside of it. So, the idea that physically 1.5 million people could fit into what are essentially sand dunes is not realistic.

Secondly, the other part of the ‘safe area’ is in Khan Younis, and Khan Younis has been subject to savage bombardment over the past several weeks. So it may have been declared ‘safe’, but we don't know how ‘safe’ is determined. Does this mean safe from future bombardments?

What we have is the risk of people coming back to bombed out buildings, to unexploded ordnance, going back to conditions that are the most awful of conditions and that are very, very unsafe.

And of course, half the population that's at risk of displacement are children, because half the population of Gaza is under 18. So you will have children rummaging around in the ruins of bombed-out buildings and at major risk of injury and death from an exploded ordnance.

So on all levels, in all ways, the evacuation plan is not realistic. And then, as I said earlier, there's no way to get the supplies in.

We do not know on what basis Israel assesses that the humanitarian needs of the forcibly displaced population will be met. Those questions don’t seem to be being asked. We will do what we can, but meaningful assistance and preparedness for something of this scale is going to be extremely difficult, if not impossible.

The New Humanitarian: Have UNRWA and other aid agencies been able to pre-position supplies and establish aid infrastructure outside of Rafah?

Rose: We have some supplies around Gaza. We’re providing aid to 2.3 million people inside Gaza. UNRWA has been providing food to 1.9 million people, and most of these people are outside of this evacuation area. So we have some storage space, and we do have some supplies in stock. We’re looking at moving some of those supplies to kind of spread the risks around.

But, I mean, the world knows we’ve been living a hand-to-mouth existence in Gaza since October. Actually, the population has been leading a hand-to-mouth existence since the blockade came in in 2007. But essentially, what comes into Gaza one day gets distributed the following day. So we have a few days worth of supplies, but no more than that.

And, as I said, without fuel to move those supplies around, it’s going to be very difficult. As I speak, our teams are out in Khan Younis doing assessments, doing renovations, seeing what can be fixed, looking at some of the buildings that were damaged during the operation in Khan Younis to see if they can function as storage, as office space, etc. So, we do what we can. We’ve been doing what we can since October. But what we are able to do is quite limited.

The New Humanitarian: What impact will the Kerem Shalom and Rafah border crossings being closed have on the ability to get aid into Gaza and on the ability of UNRWA and other aid groups to operate?

Rose: These are the lifeblood of the humanitarian operation inside Gaza. We've seen the videos of the passenger terminal at Rafah being taken over and the gratuitous vandalism that appears to have taken place, running over signage and gardens and ripping up roads, etc.

Almost all aid and all humanitarian supplies that have come into Gaza since October have come in through Kerem Shalom and Rafah. There have been small amounts that have come in through Erez [in the north of Gaza]. These are tiny amounts. We've all heard talk and we've seen the plans for the maritime route, but we’ve been clear throughout that those are additional supply lines. They complement what we’ve got at Kerem Shalom and Rafah. They in no way can replace it.

We are also not in a position to serve southern Gaza from northern Gaza. It’s just not an option. So, without those supply lines, the situation will very quickly break down.

The New Humanitarian: Can you expand on why serving southern Gaza from northern Gaza is not an option?

Rose: It's not an option in terms of the volume of supplies that are able to come in. The volume of supplies that are coming in through Erez right now is minimal and is not sufficient to even meet the needs of people in the north. So the idea that we would send them down to the south, there just wouldn't be enough of it.

Secondly, it's not an option because of the difficulties and the time it takes to bring goods across the Wadi Gaza checkpoint [the gateway to the north of the enclave that all people and humanitarian supplies have to pass through, forming a major bottleneck for aid groups] into the middle area and southern Gaza. It’s not realistic to mount a large-scale aid operation from the north to the south.

And, for UNRWA in particular, which is by far the largest aid agency inside Gaza, we are not being permitted to bring aid in through northern Gaza. So, even if the ability was there to do it – which it isn’t – then you’re essentially hobbling the largest aid organisation in Gaza from being part of the response at a time when we need to throw everything that we have at this, given the famine situation in northern Gaza and what can only be coming in southern Gaza if conditions remain as they are for a sustained period of time.

The New Humanitarian: If the Israeli military campaign in Rafah continues to escalate, what impact will that have on the humanitarian situation for people there?

Rose: We’ve already got the largest number of people anywhere in the world facing catastrophic food security conditions. When you think that there’s only 2.3 million people inside Gaza, that tells its own story. The population is on life support, and that life support is failing. The only way we’ve been able to do what we’ve been able to do is through what’s coming in through Kerem Shalom and Rafah.

If the Israeli military operation continues, the last remaining city in Gaza that has not been destroyed will be destroyed. You’ve got 1.5 million people who are extremely vulnerable. Many have been displaced five or ten times already. Now, they face another round of displacement. Where do they go? Previously they have headed to ‘safe zones’ because they had not been subjected to bombardment.

We will essentially see the completion of that bombardment, geographically, if a full-scale operation into Rafah goes ahead. Everyone will have lost everything if this goes ahead. And there’s very little we can do as a humanitarian community.

The New Humanitarian: UNRWA has said that it will not evacuate Rafah. How did you come to that decision, and what does it mean, practically?

Rose: We are not evacuating from Rafah because we are still able to operate where we are. We're in an area two or three miles to the northwest of the evacuation zone. So right now, there is absolutely no reason for us to evacuate. We are not alone. The UN as a whole is staying put in Tel al-Sultan and Rafah in terms of the physical headquarters of the aid operation.

Until such a time as security conditions don't allow us to remain, we will remain.

Edited by Andrew Gully.