A Security Council resolution that allows the UN to deliver aid across Syria’s borders into opposition-held areas without the permission of President Bashar al-Assad is up for renewal and, as with so many diplomatic manoeuvres in the seven-year war, all eyes are on Russia.

The UN relies on Resolution 2165, first passed in 2014, to use two crossings with Turkey to bring aid to millions of civilians in Syria’s rebel-held northwest, many of whom have fled their homes elsewhere in the country. A government offensive to retake the area, which includes Idlib province, is currently on hold after a deal brokered by Turkey and Russia.

The lion’s share of cross-border assistance is delivered by groups outside the UN system, but humanitarians say the UN provides a reputational and organisational backbone that bolsters the entire aid operation – one that risks being lost if Russia vetoes the resolution.

In an interview on Monday with IRIN’s Ben Parker, UN aid chief Mark Lowcock said there is “no plan B” for delivering UN assistance without the backing of UN resolutions, as the Syrian government is “not willing” to allow aid to cross its front lines to reach rebel-held areas.

UN General Assembly Resolution 46/182, which is the basis for all UN international humanitarian action, states “humanitarian assistance should be provided with the consent of the affected country”. The Geneva Conventions also say the consent of affected states is required but may not be arbitrarily withheld.

In the early years of Syria’s war, many NGOs said that aid was being arbitrarily withheld to border regions and argued that by bringing aid in across borders they were therefore safely within the bounds of the Geneva Conventions.

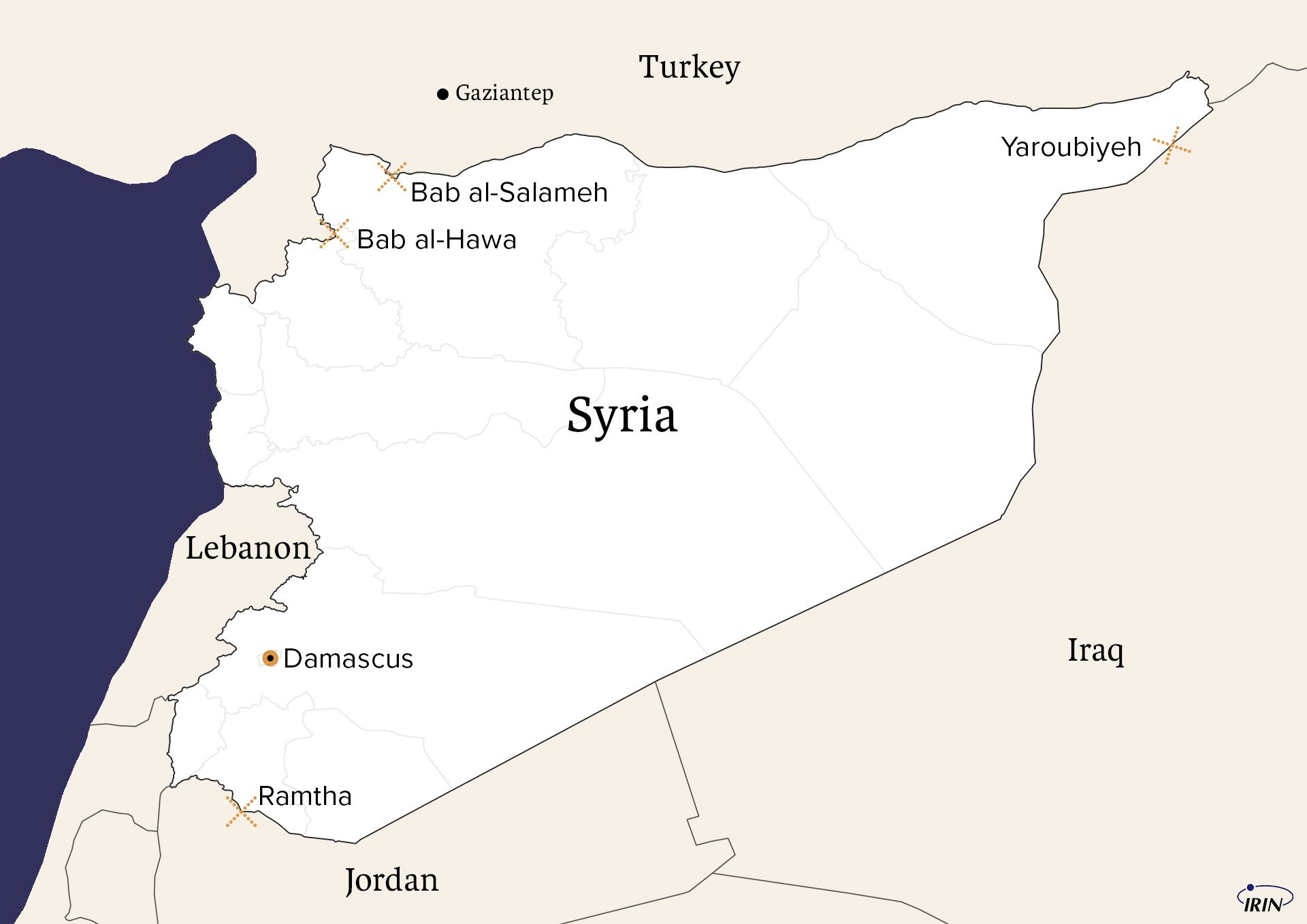

But that wasn’t good enough for the UN, which had an assertive member state – Syria – saying no to assistance; to work under 46/182 the body needed a Security Council resolution. They got it with 2165, which said that UN agencies no longer had to request permission from al-Assad, they only had to notify Damascus before crossing the border through one of four entry points:

- Bab al-Hawa, from Turkey into Idlib in northwestern Syria

- Bab al-Salameh, also from Turkey into northwestern Syria

- Ramtha, from Jordan into southern Syria

- Yaroubiyeh, from Iraq into northeastern Syria

In 2018, the Ramtha crossing with Jordan was retaken by the Syrian army. Yaroubiyeh has been used sparingly, partly because of insecurity in Iraq.

As a result, 2165 now mostly matters for northwestern Syria – an area which, according to statistics compiled by the Mercy Corps Humanitarian Access Team and made available to IRIN, holds some 3.3 million Syrians, three quarters of whom live in the wider Idlib area. (However, population statistics in Syria are highly unreliable.)

Although 2165 does not require permission from Damascus, a demanding apparatus of border inspections came with the resolution, staffed by the UN and funded by donors.

New UN hubs sprang up in the Turkish city of Gaziantep and in Amman, from where UN agencies began to organise a regular supply chain for civilians in border areas outside al-Assad’s control.

With 2165 set to expire 10 January, Kuwait and Sweden are readying a one-year renewal. The two Security Council members will circulate a draft “soon”, Kuwait’s ambassador to the UN said on Friday.

“The resolution allows the UN and its partners to deliver humanitarian aid through the most direct routes to people in need in Syria,” Per Örnéus, Sweden’s special envoy for the Syria crisis, told IRIN. “The mandate is strictly humanitarian, offering a lifeline for millions of people,” he added. “It must be extended.”

The resolution has been renewed annually since 2014, but last year’s vote caused friction – and nail-biting for humanitarians working on Syrian aid operations – when Russia singled it out for harsh criticism, saying it threatened Syria’s sovereignty.

While al-Assad’s top ally on the Security Council opted not to veto last year, Moscow is sending out mixed signals as the January deadline approaches. Renewal looks more likely than not, but it is far from a sure thing.

Major impact

Resolution 2165 was first mooted at a time in the war when Damascus regularly denied UN requests to bring help across its borders to areas dominated by the opposition. It allows the UN to bring shipments in at specific points, as long as it notifies the Syrian government.

Humanitarians insist 2165 is crucial, and stress that its importance should not be measured just in terms of the actual quantities of aid delivered.

In 2017, UN agencies like WFP or UNHCR provided only around 20 percent of the cross-border aid deliveries to Syria. NGOs outside of the UN system brought in the rest, often delivering it through local Syrian organisations and importing their aid mostly through commercial channels (the official Bab al-Hawa and Bab al-Salameh crossings with Turkey) or a separate network of crossings monitored by the Turkish Red Crescent.

Most goods – like food and fuel – enter northwestern Syria on a for-profit basis, imported by Turkish or Syrian businessmen.

Aid agencies say more than three million people live in northwestern areas not controlled by the Syrian government, though population estimates in Syria are notoriously unreliable and have in the past often suffered from overcounting.

Without 2165, private traders and NGOs could still bring goods in, as long as Ankara approved. But UN involvement would likely end immediately if Damascus objected, and, while NGOs might be able to fill the tonnage gap created by a UN pull-out, losing 2165 would be a big blow to the humanitarian relief effort.

A source with significant experience of the Syrian aid operation, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said 2165 brought a “significant increase in the overall response” by helping “what was a fragmented humanitarian community come closer together, coordinate, build institutions, and deliver a more joined-up and effective response as of 2015.”

Mathieu Rouquette of the Syria International NGO Regional Forum, a network of 70 aid groups working in Syria, said the resolution “still underpins access to millions of people in areas that we are not able to reach from Damascus.”

There would be other impacts too.

Aid operations would likely suffer if the UN stopped planning and coordinating deliveries in the Turkish border town of Gaziantep, as many NGOs rely on the UN hub for logistical support.

“The resolution is what underpins the overall architecture of the humanitarian response,” explained Rouquette. “So an end to that would necessarily mean a return to a fragmented humanitarian response.”

Moving to Damascus

Aid workers said the loss of a UN role in the cross-border response would also accelerate the shift of international NGOs from opposition-held areas towards parts of Syria controlled by al-Assad’s government, while enhancing Ankara’s influence over cross-border operations.

The Syrian government has told most NGOs that in order to register in Damascus they must end their “illegal” cross-border work under 2165.

Many international NGOs were originally drawn into cross-border work early in the war by US and EU funding streams geared to shore up opposition regions, while others branched out from working with Syrian refugees. They also filled in the gaps before 2165 when the UN could only assist Syrians in state-controlled areas, except for very rare “cross-line” exceptions, like convoys from Damascus to besieged areas.

Some chafe under the rules laid down by Turkey: Ankara has told international NGOs they can either provide cross-border assistance from Turkey to Syrians in the rebel-held northwest, or work in in northeastern Syria, which is controlled by US-backed Kurdish groups hostile to the Turkish government. They can’t do both.

In 2017, Turkish authorities ordered Mercy Corps to leave the country, apparently as punishment for its work in the Kurdish-held regions.

With al-Assad now back in charge of most of Syria, and the sole remaining cross-border hub in Gaziantep catering to an area of northern Syria that is largely under Turkish tutelage, many NGOs have come to view Damascus as the best option.

“The resolution is what underpins the overall architecture of the humanitarian response.”

Several NGOs have voiced concerns about what being stripped of the UN cover would mean for the overall optics of cross-border work in a place like Idlib province, which is currently controlled by rebel groups – some of whom are designated terrorists by the United States and other countries.

Bab al-Hawa has been controlled by the UN-designated al-Qaeda spinoff Tahrir al-Sham since 2017 and has been at the centre of diversion scandals that triggered Western aid cutoffs and NGOs suspensions. USAID is now rolling out a stricter inspection regime, further tilting the risk analysis for NGOs pondering where to focus their operations.

On Monday, the Charity Commission – the UK government department that regulates and registers NGOs in England and Wales – issued an alert, warning “there is a risk that a terrorist organisation may financially benefit from any aid passing through the Bab al-Hawa crossing.”

Tripping over counter-terrorism sanctions can cause very serious problems for NGOs: legal issues, economic losses, reputational damage, and donor flight. In the face of these risks, UN involvement offers them and their donors a sense of reassurance and legitimacy.

Should the cross-border operation be stripped of its UN participation, it would likely prod more Western NGOs to withdraw from Syria altogether or rebase in Damascus on terms set by al-Assad. And, as a result, the northwestern cross-border response would come to rely even more on the Turkish Red Crescent and other Ankara-friendly groups.

Russian roulette

With a resolution expected on the table in the coming weeks, a Swedish diplomatic source told IRIN that Turkey and Russia are now the “key actors” in the battle over 2165. Ankara may influence Moscow’s views, but it is Russia’s vote in the Security Council that will be decisive.

Moscow joined Western states in voting for resolution 2165 and extensions of it in 2014, 2015, and 2016. But last year’s vote was different.

In November 2017, Russian Ambassador to the UN Vassily Nebenzia slammed 2165 as “unprecedented and extreme” and said it “usurps Syria’s sovereignty”. A Foreign Ministry spokesperson accused the resolution of contributing to “the division of Syria”.

US-Russian conflict in the Security Council was then at a high pitch after Nebenzia cast three successive vetoes to shut down a UN investigation that found the Syrian military had gassed civilians, and many humanitarians feared that 2165’s time was up.

However, Moscow relented and said it would abstain from voting in return for a review of cross-border aid and monitoring procedures by the secretary-general, allowing 2165 to be renewed on 19 December 2017 with 12 votes in favour and none against. (China and Bolivia also abstained.)

While aid workers were relieved, many assumed that the resolution was unlikely to be renewed again in recognisable shape.

But something happened soon after that: Instead of ramping up attacks on 2165 as the vote approached, Moscow fell silent.

IRIN has learned that a Russian diplomat unexpectedly told NGO representatives in Geneva last month that cross-border aid “should remain and should remain as it is”.

Four humanitarian and two diplomatic sources confirmed that Russia voiced support for continued cross-border aid.

Most attributed Russia’s apparent 180 degree turn to the 17 September Turkish-Russian agreement over Idlib, which seems to reflect an unspoken understanding that northwestern Syria will effectively remain in Turkish hands for the foreseeable future.

“The only explanation I can think of is that there was some sort of deal struck between Turkey and Russia as part of the broader negotiations over Idlib in which Turkey sought non-opposition on this to avoid having to let in another wave of refugees”, a humanitarian source told IRIN.

Russia could also have decided that it is not currently in its interest to hand back control over cross-border aid to al-Assad, when it currently has that control itself through the Security Council. Even then, Moscow may of course seek to dilute or amend Resolution 2165.

After abstaining from voting on a renewal in 2017, Russian Ambassador to the UN Vassily Nebenzia as recently as June called the UN secretary-general’s positive review of the resolution “disappointing” and said “it is essential to work to end the mechanism”, warning that the UN needed to “prepare for the closure of cross-border operations”.

More recently, Moscow has signalled it will not look to block renewal. But some supporters of 2165 worry that Russia may be trying to lull rivals into a false sense of security, while others fear that poorly handled debates or unrelated quarrels could still encourage a veto.

“To be honest, I’m not convinced the renewal will be so easy,” one humanitarian source said, accusing parts of the aid community of showing a “baffling” faith in renewal and of failing to prepare for other outcomes.

On 29 November, Russia’s deputy UN ambassador Dmitry Polyansky told the Security Council that terrorist-listed groups are exploiting cross-border support and insisted that the “significant changes” on the ground in Syria in 2018 require “commensurate adjustment of the cross-border mechanism”.

Polyansky did not elaborate, but even if Moscow has decided to let 2165 live until further notice, there are a number of limited amendments that may be in the Russian interest.

Russia could, for example, condition renewal on new language that reinforces al-Assad’s legitimacy or supports reconstruction aid for Syria, which would infuriate Western nations. And while Turkey would presumably oppose the UN’s loss of access through Bab al-Hawa and Bab al-Salameh, stripping away UN access to US-backed Kurdish areas through the third crossing at Yaaroubiyeh might be another matter.

If Moscow wants to have 2165 on the table more often, as a source of leverage, it could also seek to cut the time between renewals.

The Russian Foreign Ministry, the Russian UN mission, and representatives of the Syrian government all failed to responded to IRIN’s requests for comment.

(TOP PHOTO: Internally displaced Syrians in northern Aleppo province's Tel Rifaat collect aid supplies. CREDIT: Antwan Chnkdji/UNHCR)

This work was supported in part by a research grant from The Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation

al/as/ag