Some call it nshima or sadza, others pap or ugali. Whatever the name, maize meal is the staple food across much of southern Africa and large parts of eastern Africa.

Boiled and stirred into a stout white dough, it’s the starch accompaniment to most meals. So entrenched and seemingly traditional, Malawians call their favourite variety ‘maize of the ancestors’.

But maize is not as traditional as most people think. It’s an import (as are bananas, cassava, beans and potatoes), and in much of the interior of Africa, only a little over a century old. Its rise to dominance as a food crop has been incredible, but its future is far less assured.

Central Mexico is the original home of maize. It arrived along the west and east African coasts in the 1500s, before spreading inland, following the trade routes. Farmers appreciated the significant advantages it had over indigenous grains – millet, sorghum and rice.

Corn becomes king

Maize is a carbohydrate champion. It delivers a second harvest within a single season; its outer husk provides good protection against bird damage; it requires less work to cultivate; and it proved an excellent “pioneer” crop, opening up new frontier forest settlements.

Maize slotted easily into the food production chain, but initially only as a niche crop, complimenting a complex cropping system adapted by farmers to the poor fertility of Africa’s soils and its capricious climate.

That all changed in the beginning of the last century when maize vaulted into pole position as a mono-crop in southern Africa and Kenya. What helped drive the transformation was the British colonial economy and the demand for Africa’s white maize on the London starch market.

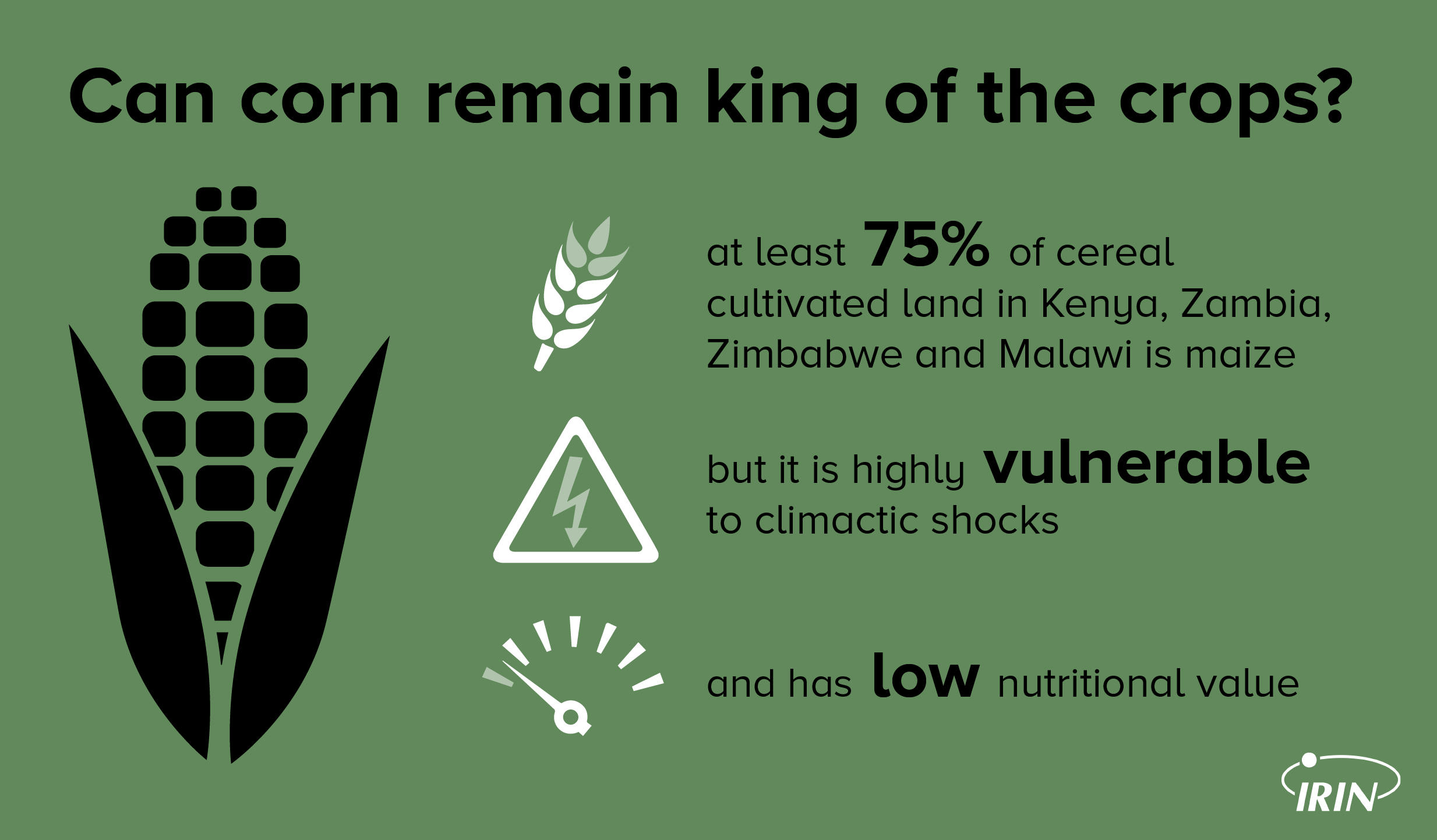

The ease of maize production on homesteads helped release men into the labour market, and the spread of hammer mills enabled the easy local processing of maize into flour. Today maize occupies three quarters or more of the land under cereal cultivation in Kenya, Zambia and Zimbabwe. In Malawi, it’s as high as 89 percent.

Maize has pushed original drought-tolerant crops like millet and sorghum out of the market. A powerful industry brands and packages it as the cornerstone of family life.

But Africa imports around 28 percent of its maize from overseas. Maize never became the long-predicted foundation of an African “green revolution”, and climate change is increasingly exposing its limitations as a reliable ever-bountiful crop.

We have a problem

The downside to maize is that it’s “highly sensitive to deprivation of water, sunlight and nitrogen,” wrote James McCann, an agricultural historian at Boston University. “Even a few days of drought at the time of tasseling [its maturing stage] can ruin a crop. Thus, maize monocultures are extremely vulnerable to environmental shocks.”

Maize also has a relatively low nutritional value – unlike the millet and sorghum it displaced. What that means is that in poor households, which cannot afford the vegetable and meat accompaniment, filling your child’s belly with maize meal doesn’t prevent malnutrition.

Kitui is an agricultural town in eastern Kenya on the frontline of climate change. It’s an arid to semi-arid zone, with seasonal rivers that dry up in the summer, making irrigation a challenge. It has a poverty index slightly below the national average.

Pastor David Mutinda farms just over two hectares and has noticed the weather is now increasingly erratic, which moisture-sensitive maize does not like. “The rains are no longer consistent, they either don’t come, or come at the wrong time, which affects which crops can be grown,” he told IRIN.

Mutinda has joined a programme run by Farm Africa, an NGO operating in east Africa to help smallholder producers boost their incomes.

In Kitui, Farm Africa promotes drought-tolerant cassava and sorghum, as well as hardy legumes as cash crops. It has introduced conservation agriculture, including minimum tillage techniques and terracing to help preserve soil moisture.

Mutinda is something of a model farmer. He grows cassava for both the market and his table, green gram (mung beans) that he sells to a local seed company, and has added cowpeas, mango trees and poultry to a steadily expanding business. He still has a little maize – there’s a cultural importance to being able to roast a few green cobs for your children as a treat – but his household no longer depends on it.

“I’m positive about this season because of the type of crops I’ve planted,” he told IRIN. “They’re able to resist drought so I can do well with them.”

Lydia Gathenya of Farm Africa says they are working with farmers to change the subsistence model of small-scale production. By increasing linkages with markets, the NGO is transforming farming from “drudgery” into a money-making business. “You don’t need to grow what you consume anymore,” she added. “If you want to eat maize, you can go and buy it.”

Africa will be one of the region’s hardest hit by climate change. Agriculture accounts for 75 percent of employment, with nearly all production rain-fed. The continent’s ability to adapt is hamstrung by the size of the bill to build resilience, institutional weakness, and the lack of political support to smallholder farmers.

Southern Africa is one region predicted to become even drier. There have been regular droughts since the 1990s, with currently 49 million people facing hunger due to an El Nino year – more than double the number affected by the last great drought in 1991/92.

The fight back?

The answer from the scientists is better drought-resistant maize. A Mexican-African project to develop Stress-Tolerant Maize for Africa was launched in March. The drought-proof hybrids are expected to increase productivity by 30 to 50 percent, and the project – funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation – aims to have the seeds in the hands of 5.5 million smallholders in 12 countries by the end of 2019.

But the evidence suggests that the African seed market is complicated. According to a new study, farmers access 90 percent of their seed from informal systems rather than commercial agro-dealers, with local markets linked to new varieties only in an “ad hoc manner”.

That frustrates the uptake at scale of new, improved varieties. “There seems to be an investment lacuna between the science of plant breeding, which receives substantial funds, and the science of delivery,” the study by researchers Shawn McGuire and Louise Sperling suggested.

“My experience is that where you have challenging environments, you should adopt the most suitable crop,” said Edgar Kadenge of the Gwassi Integrated Community Empowerment Project in western Kenya. “You shouldn’t panel beat the crop, planting in an unfavourable environment, and expect good yields. Ultimately, you are just contributing to food insecurity.”

According to a report by the International Food Policy Research Institute, the 1990s marked the beginning of the period of uncertainty for maize after close to a century of undisputed reign. Climate variability is one factor, but so too were the end of state input subsidies and market support demanded by IMF-imposed austerity programmes, and the sharp drop in investment in public sector agricultural research.

African agriculture needs a farm lobby and the political will to deliver investments that will benefit smallholders, says the study. Although governments regularly trot out the policy slogans around building resilience, the perennial food crises in southern Africa, for example, suggest the primary audience is donors and the aid system – not the farmers.

“Given reasonable assumptions about future productivity improvements, it is unlikely that maize can provide the net revenue on the millions of farms that are 0.5 to 1 hectares or smaller to generate substantial income growth, especially in the semi-arid areas,” the IFPRI study noted.

Gathenya, pushing her cassava and market-led alternatives in Kitui, warns that “behaviour change can’t be abrupt”.

Like any good farmer, she knows that sustained success requires patience and careful tending.

oa/ag