Economists say it will take trillions of dollars to soften the impact of coronavirus in the developing world. Money is needed to fund welfare for millions of adults and children facing destitution – or death – from the crisis, through sickness, unemployment, or inflation.

Below, we summarise some of the major givers, and which agencies and countries have called for what support in the humanitarian (short-term) aid sector. But tracking aid funding is notoriously hard, so check out the second section too – on the many pitfalls in the counting.

PART I: The pots

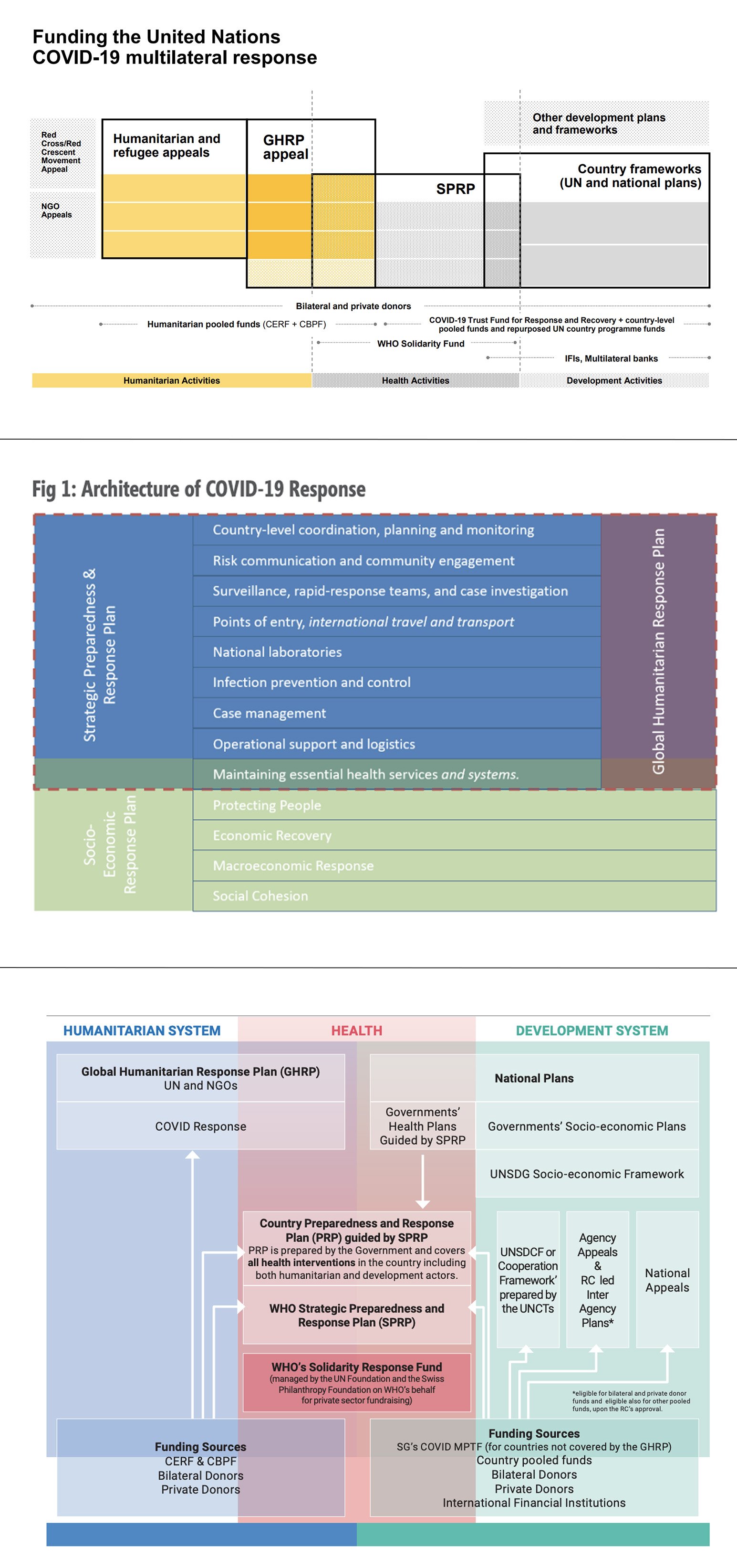

The UN has organised its COVID-19 responses into three main thematic plans: health (under the World Health Organisation), humanitarian (under its emergency aid coordination body, OCHA), and socio-economic (under the United Nations Development Programme, or UNDP).

WHO preparedness and response plan

The WHO leads the UN on public health, and it produced a funding proposal to help low- and middle-income countries with the public health aspects of COVID-19. The first version of the Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan called for $675 million for the period February-April. An expected revision, likely to have a much larger price tag, is now overdue, but the WHO has not announced when it will be released.

The UN and NGO Global Humanitarian Response Plan

The COVID-19 Global Humanitarian Response Plan, or GHRP, adds over 20 percent to a bill for international emergency funding that already stood at some $30 billion.

The UN’s humanitarian wing, OCHA, has classified 63 countries as needing humanitarian assistance due to COVID-19, at a cost of $6.7 billion for the rest of 2020. Most of those countries already had a budgeted response plan for their pre-existing crisis needs. Each of those has now been increased, with OCHA asking for more corresponding donor money. Other countries not previously classified as having a humanitarian crisis (like Iran) have also been added to the list. Refugee populations living in a range of hosting countries also need extra help, and estimates of their needs have been increased by the UN’s refugee agency, UNHCR. The GHRP has received about $1.1 billion as of 3 June.

The UN’s COVID-19 Socio-Economic Framework

For needs beyond the “humanitarian”, and the public health emergency, the UN has a third concept, and a fundraising target of $1 billion, with a leading role for its development aid arm, UNDP, which will deal with the broader fallout and the longer term response. Some donors have started to earmark funds for the post-disaster phase in a multi-donor trust fund championed initially by Norway.

The Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement

The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies and its sibling, the International Committee of the Red Cross, which works exclusively in conflicts, are asking jointly for $3.1 billion. Those targets more than tripled a previous appeal. So far, the IFRC has raised $128 million – to be divided between its Geneva HQ and member societies. The ICRC said it has received $124 million so far – 10 percent of the $1.24 billion target it intended to be spent in 2020.

Other humanitarian and aid agency appeals

Save the Children asked for $100 million, its largest ever appeal. Several other large international NGOs have asked for between $25 and $80 million each. Some of those amounts would also make up part of the GHRP – the UN-led appeal includes projects run by NGOs. Others, including Médecins Sans Frontières, have invited donations without setting a target. Many NGOs prefer not to earmark donations for a specific operation, so that funds can be transferred according to changing circumstances.

The World Bank

The World Bank’s initial announcements suggested about $3.3 billion of grants could be included in a total package of $14 billion. It has since updated that envelope to $160 billion over 15 months. Public statements have said $50 billion would be made available as grants or highly concessional loans. The Bank did not answer email enquiries as to how much would be spent as grants. It lists $1.9 billion in a first round of disbursements to 25 low- and middle-income countries that includes grants and loans.

The International Monetary Fund

The IMF has lent over $20 billion to countries to help with COVID-19. The Fund is almost entirely a provider of loans, but also has a special facility to allow countries to miss some debt repayments – through its Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust. The trust receives money from donors that is used to pay the amounts due to the IMF from debtor nations. It is largely funded by Japan and the UK, and has so far covered repayments of $229 million due from 26 countries.

Private sector

There is no central listing of private companies’ international emergency grant-making. Some report voluntarily to the UN’s FInancial Tracking Service. US-based Candid provides a listing of COVID-19 charitable and philanthropic activities, most being domestic action by US non-profits. US-based Devex has gathered COVID-19 financing announcements (not development or international aid-related) into a $17 trillion listing. Often, as in the case of the Jack Ma Foundation – which has emerged as one of the larger donors – it consists mainly of in-kind donations of goods, supplies, or transportation, and the cash equivalent value is not published. Some contributions from the private sector are even harder to evaluate: for example, advertising space provided by Google to the WHO cost the company nothing, but could be evaluated as a cost in terms of lost revenue.

Military assets

Cargo aircraft and military field hospitals have been deployed to support the delivery of supplies to COVID operations. Those also are generally done without a specific costing being announced.

PART II: The pitfalls

Here comes the health warning: we’ve listed above some of the main channels of international help, some of the biggest humanitarian appeals, and some dollar amounts. But at the best of times, it’s tough to trace international aid in anything like real time, and the multidimensional crisis of COVID-19 makes this even harder. As you can see above, there are multiple appeals, funding streams, and operators, and there’s no easy way to track them all side-by-side. So, worth bearing the following in mind when looking for actual money flows:

Pledges: Donor countries, billionaires, and companies announce overall spending amounts, but it can be months or years (or never) before all the money reaches the ground.

New versus old: Many pledges include previously committed money. That recycling makes the donor sound more generous, and it may mask cuts to other planned activities.

Timeframe: Plans, pledges, and announcements often don’t specify the timeframe for spending: but whether the money is spread over months or years makes a big difference.

Loans versus grants: The World Bank, and its cousins like the Asian Development Bank, have announced some $240 billion of resources, most of that in loans. Helping countries to borrow on low-interest terms can help, but grant aid and loans should be counted differently.

Definitions: “Development” (longer-term socioeconomic aid) and “humanitarian” (emergency) funding are usually counted separately (joining them up better is a long-running issue). The aid response to COVID-19 will absorb money from those and other pots; all report their spending differently.

WHO: As well as scientific and policy work, the WHO implements aid projects and acts as a funding intermediary. It’s collecting funds for its own work and for passing on to developing countries, and some of that fundraising and expenditure is reported separately from other UN spending.

In-kind: When supplies – such as personal protective equipment or ventilators – are flown in by chartered flights, the cost of both the items and the transport are rarely published, so are often missing from reported aid spending, even though the costs of flights and specialised equipment may be significant.

Double counting: Aid funds often pass through several agencies. Japan and the UK for example, have donated to an IMF fund for debt relief. Many donors contribute to OCHA’s pooled funds. The amounts may appear in announcements from the two countries and from the intermediary, in this case the UN or the IMF.

Vaccine research isn’t all aid: A working vaccine will help everyone, so a wealthy country’s spending on vaccine research for a disease that occurs everywhere usually can’t be counted as aid. There are some large amounts pledged for vaccine research, but It’s a mix of self-interest and potential benefit to less wealthy countries (in making the drug affordable).

What counts as COVID-19?: Funding to pay health workers, or supply clean water, or to pay an unemployment allowance can be addressing the impact of COVID-19 but go beyond the narrow needs due to the virus, bringing wider benefits. Also, some aid groups may “COVID-wash” their pre-existing programmes by relabelling them.

Data: There is no single, central database of international aid that is updated in real time. The UN tracks humanitarian funding (but that doesn’t include everything: the World Bank’s COVID-19 grants generally do not appear). And the other main source, the OECD, publishes after as much as 18 months. Data shared via the International Aid Transparency Initiative can provide detail on donations notified in the correct format, but coverage is patchy and the data can be challenging to use.

Domestic spending: National governments are spending on welfare and safety nets, paid for by tax and other government revenue (or debt), but tracking those expenditures is rarely lined up against the inflows of international funding. For middle-income countries at least, domestic resources can dwarf aid spending. For example, South Africa’s measures amount to between $26 billion and $46 billion.

Extras: In the case of Uganda, a $316 million COVID-19 appeal was prepared locally, agreed between the government and local offices of the UN and NGOs. However, the full amount doesn’t feature in the UN’s global GHRP humanitarian appeal, so the needs and donor responses again don’t match up between the HQ and field-level funding tracking.

bp/ag

Subscribe to our newsletters to stay up to date with our coverage.