At a Glance: Burkina Faso’s deepening crisis

- 560,000 people displaced, and numbers still rising.

- More than 1.2 million people short of food.

- Insecurity is cutting off swathes of the country to aid workers.

- Negotiating access with armed groups is proving difficult.

- Lack of funding is undermining the humanitarian response.

A surge in violence by jihadists, local militias, and militants – along with spiralling inter-communal attacks – has created in Burkina Faso one of the fastest-growing displacement crises in Africa, according to the United Nations.

The rapid escalation this year, in a West African nation not long ago held up as an example of peaceful religious and ethnic coexistence, has caught aid groups and the government by surprise.

The slow shift by donors and the government away from a focus on development projects to addressing emergency needs has held back the response, aid workers and officials told The New Humanitarian earlier this month, during visits to the north and east of the country to report on the expanding violence and its impact on Burkinabes and those trying to respond.

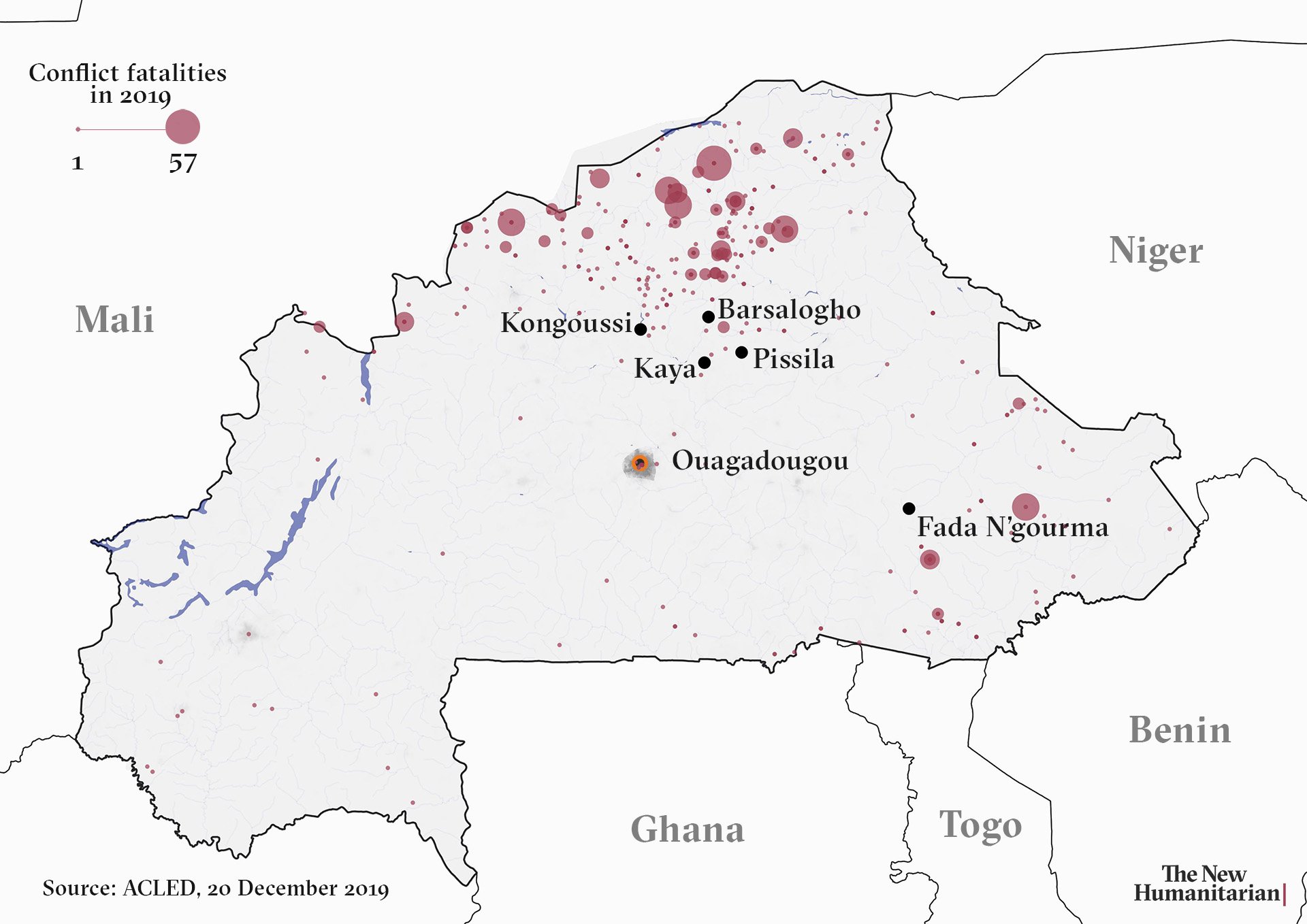

More than half a million people are internally displaced, a 544 percent increase since the start of the year. Almost 2,000 people have been killed since January, according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, which collects and analyses conflict information.

Attacks once targeted at government institutions and defense, security, and community leaders have shifted towards civilians, including those perceived as supporting the government or involved with pro-government self-defence militias.

The violence is gradually cutting off swathes of land, making it nearly impossible for aid groups to access many communities in need of assistance.

Over 1.2 million people are needing immediate food assistance, almost four times more than last year, according to the latest food security report from December, conducted by the government, the UN, and aid groups.

More than two million people will be in need of life-saving assistance next year, double the number at the start of 2019.

With few formal internal displacement camps, many of those forced from their homes due to violence are sheltering with relatives or friends, while others are living in crowded, makeshift sites or public buildings such as schools, or have even sought refuge under trees. As of September, approximately 42,000 people were living in 92 schools, according to UNICEF.

“The situation is really unprecedented for Burkina Faso,” said Kristen Knutson, head of the UN’s emergency aid coordination body, OCHA.

“The impact on the affected population has been quite severe, and the number of people in need of assistance has grown rapidly over the course of the year,” she said. “Unfortunately, the scale of humanitarian need is likely to increase in 2020”.

This briefing looks at the rapidly expanding humanitarian emergency, and the challenges faced by aid workers and Burkina Faso’s government in trying to respond.

What has changed this year?

In January, there were approximately 87,000 internally displaced people in Burkina Faso, according to the UN. A surge in violence – in the Sahel, North, Centre-North, and, more recently, East regions – means there are now at least 560,000. More than two million people will be in need of life-saving assistance next year, double the number at the start of 2019.

More than 90 percent of displaced people are seeking refuge in towns with family or friends, according to the UN.

Some aid workers say that community generosity, where people have opened their homes to others who are displaced, has partially contributed to delays in providing shelter.

“There has been so much solidarity within host communities, but the need to provide more shelter support has become a critical priority as the number of people displaced has risen sharply over the months,” said Knutson from OCHA. “We’re still playing catch-up.”

Several aid workers told TNH there had been at least a six-month delay in aid groups being able to provide people with aid, largely due to a lack of funding.

When Silvia Beccacece, global emergency response team leader for the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), arrived in the country in May, there was basically no shelter being provided to displaced people, she said. “Part of the delay was due to a lack of funds and also a lack of global attention to the crisis,” she noted.

“If nothing changes in two months, we’ll run out of resources.”

The NRC has been working with the government to move people out of public buildings, especially schools, and into temporary shelters. Since October, the government allocated several plots of land – in Barsalogho, Kaya, Pissila, and Kongoussi in the Centre and North regions – to serve as informal camps for thousands of internally displaced people.

In Barsalogho town in the country’s north, one of the last havens where people feel relatively shielded from attacks, the group set up more than 830 shelters, each housing approximately seven people. NRC plans to erect another 2,500 shelters in three locations over the next six months.

The violence has also impacted healthcare: more than 800,000 people have limited or no access to services; 71 health centres have been forced closed; and 75 others have been damaged, according to the UN.

What’s the biggest concern among residents?

Lack of access to food.

In early December, TNH met with displaced people from across the country. All worried how they were going to survive.

Seated on a mat under a tree on the edge of Fada N'gourma town in the country’s east, Yanga Amadou pointed to his cattle grazing nearby.

“If nothing changes in two months, we’ll run out of resources,” he said.

At the beginning of the month, the 66-year-old fled his village of Kounkounfouanou with 27 members of his family after he found three of his brothers murdered, their throats slit, lying on the floor of his house.

He doesn’t know who is responsible: jihadists, the Burkinabe military – which has been accused of human rights violations – or the Koglweogo, a local ‘self-defense’ militia also accused of atrocities. All had been fighting in the area, he said.

Having fled before their crops were ready to harvest, Amadou said he and his family now rely on selling their livestock in order to buy food. Unsure of what the future holds, they’re rationing what little they have, eating small portions. And they refuse to spend money on rent in the city, choosing instead to live under a tree on the edge of town.

Humanitarians are concerned that access to food will only get more difficult.

"Many displaced people who have abandoned their farming and are solely relying on buying food in the market will find that their situation will only get worse, as prices usually rise during the lean season," said Julia Wanjiru, communications coordinator for the Sahel and West Africa Club, an intergovernmental economic group.

Who’s behind the violence?

Security in the country began to deteriorate after the ousting of former president Blaise Compaoré, who ruled the nation for almost three decades; his presidential guard was disbanded, leaving a security vacuum. Major attacks by Islamist militants were launched in 2016 on hotels and restaurants in the capital, Ouagadougou, and violence has continued to escalate.

Such attacks have soared since January.

In November, 37 people were killed and more than 60 wounded when a convoy with workers for the Canadian gold mining company, Semafo, was ambushed by gunmen in the east of the country. Earlier this month, also in the east, at least 14 people were killed when attackers opened fire inside a church.

A mix of groups are believed to be operating in the country, including the Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims (JNIM), an umbrella organisation that consists of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), the homegrown Burkinabe Islamist group Ansaroul Islam, and the Macina Liberation Front, headquartered in the centre of neighbouring Mali. A separate group, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), is largely active in the east.

What are the challenges for aid workers?

A lack of funding remains one of the biggest gaps in the humanitarian response. An updated UN request for funding in August increased the amount needed by 87 percent, from $100 million to $187 million. However, less than 50 percent has been funded.

Next year’s humanitarian response plan is requesting $295 million, according to the UN.

The government estimates it currently needs 100 billion West African Francs (approximately $170 million) for the emergency response, but said it can only afford one third of that, government spokesman Remis Fulgance Dandjinou told TNH.

“It’s a huge problem,” he said. “It’s the first time we’re facing this, having internally displaced people on our soil.”

Some aid workers partially attribute the gap in funding to the fact that for years donors and organisations working in Burkina Faso have focused on development and had to do very little in terms of emergency issues.

“Donor governments have acknowledged that they’ve had to convey that the situation has changed,” said Knutson. “They were focused on development until a year ago and have had to advocate within their own systems that they had to switch.” But it’s taking time to shift footing.

Aid workers and officials said the differing mandates within the development and humanitarian contexts also pose challenges.

Humanitarian agencies must maintain neutrality whether they’re speaking to the government, armed groups, or other stakeholders, whereas development agencies are closely connected to the government in trying to develop the country’s infrastructure and institutions, said Donald Brooks, chief executive officer for Initiative: Eau – a US aid group focused on increasing the safety and security of drinking water services in developing areas and crisis zones.

The differing approaches can create problems in terms of negotiating access, particularly for local aid groups that might take longer to adjust from development to humanitarian mindsets, said Brooks. Implementing the humanitarian principle of neutrality, for instance, requires them to distance themselves from their long-term governmental partners.

Brooks said he had been told by local partners that Burkinabe aid workers had been kidnapped as recently as last month in the eastern part of the country, where his organisation is based. He said he worried that those who were abducted may have been perceived as government employees because they worked closely with government officials.

Has access become more difficult?

As violence increases, areas across the country have become ungovernable and access is shrinking. The number of towns once deemed safe is diminishing, making it hard for aid groups to not only reach displaced people but also to assist those left behind.

In July, the NRC could access villages beyond the northern town of Barsalogho, but expanding attacks now prevent them from reaching those outlying villages.

“Realistically speaking there is a high percentage of the population that we don’t have access to and that isn’t receiving assistance,” said Beccacece of the NRC, estimating that the number of inaccessible people was in the tens of thousands.

“If a community accepts you and sees your services as beneficial, they are likely to protect and alert you when it’s time to get out.”

NRC would normally try and negotiate access with the armed groups, but it is often unclear which groups are operating in certain areas, and some have not yet been identified.

“We often operate in countries where conflict dynamics are clearer and you know who and where they are,” Beccacece said. “If you don’t know how to move in this environment, it’s risky.”

Most aid groups travel by road, but NRC is pushing for a UN-supported air service that would make it easier, faster, and safer to access hard-to-reach areas.

Sarah Vuylsteke, access coordinator for the World Food Programme who is currently working in Yemen, said if aid groups aren’t able to gain access because they don’t know which armed actors to engage with, then an alternative is to work through the community.

“If a community accepts you and sees your services as beneficial, they are likely to protect and alert you when it’s time to get out,” she said. Ultimately you can’t do access negotiations if you don’t know who the parties are, but you can use pre-existing community interlocutors and structures in lieu, as an initial contact and base, she noted.

How is the government responding?

Amid growing insecurity and limited resources, the government has been taking steps to respond. In the northern town of Pissila, it is trying to bring healthcare, food, and education to some 38,000 people sheltering in an informal camp, Traore Simplice, the government appointee in charge of civil and social affairs for the area, told TNH during a recent visit to the site. For instance, abandoned buildings are being converted into schools so displaced children can continue learning, he said.

Yet some aid groups are concerned that the government’s insistence on retaining tight control over the response sometimes delays assistance.

Early this month, a government representative in Fada N'gourma forbade humanitarian organisations from using their own data on the number of people registered as displaced when planning assistance, Joseph Kienon, field coordinator for Action Against Hunger in Fada N'gourma, said. Agencies were asked to rely on official government figures when delivering aid, he said, with the government official explaining that the goal was to better coordinate response efforts. However, because the government’s data is compiled manually rather than digitally, there were delays in receiving those figures, Kienon said.

“We’ve lost time because of slow registration,” said Kienon. People displaced at the beginning of December have had to wait until only a few days ago to receive help, he added.

Simplice, the government official working in Pissila, said the government’s control over the situation is a matter of “sovereignty”. It’s a priority for the state to take care of its people even if it means aid might be delayed, he added.

Brooks, of the American aid group Initiative: Eau, said local authorities refused last week to share information on which other aid organisations were working in Fada N'gourma and the surrounding villages.

“There’s a reticence of government actors to share information and to promote and facilitate a cohesive response,” he charged. “This is deeply problematic to the creation of a coordinated and concerted effort by government and the international community.”

Aid groups in the east are in discussions with the government about how to increase coordination, Kienon said.

Meanwhile, many of those who have been displaced are growing increasingly desperate.

Breaking a small nut with his worn fingers, Tankoano Mardia shared half of it with his friend seated next to him in the yard of an abandoned house where they were living in Fada N'gourma.

Mardia, the former chief of the nearby village of Natiaboani, said he had fled after jihadists killed one of his ministers. He and his family hadn’t had a meal in two days and were subsisting on nuts and occasional handout from friends.

“We had everything back in our village,” he said, hanging his head. “I need help, but I don’t want to die as a beggar.”

sm/oa/js/ag