Every year for the past two decades, an estimated 350 to 500 medium-to-large disasters have taken place globally; numbers only expected to rise further due to the climate crisis. But many, like the case studies we report on here in Peru and Nepal, receive little attention beyond the areas directly affected. As a result, the response can fall far short of what’s needed.

Disasters that fly under the radar because their casualty counts aren’t so high often also happen in the same places year in year out, causing huge long-term problems. And the fact that they struggle for aid funding and holistic relief strategies only exacerbates future disasters by forcing survivors to remain in – or return to – the same unsafe locations.

“On the local level, communities are destroyed, residents lose their livelihoods, poverty increases, and they are in a vicious cycle year after year; because every year, it's the same,” explained Melissa Allemant, humanitarian response lead at Save the Children in Peru.

A recent report from the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) predicted that disasters will rise to roughly 560 per year by 2030. “Disasters have now become a leading cause of forced migration and displacement globally,” António Vittorino, director general of the UN’s migration agency, IOM, told a recent risk reduction forum in Bali.

Read more →Why the disaster prevention agenda is growing more urgent

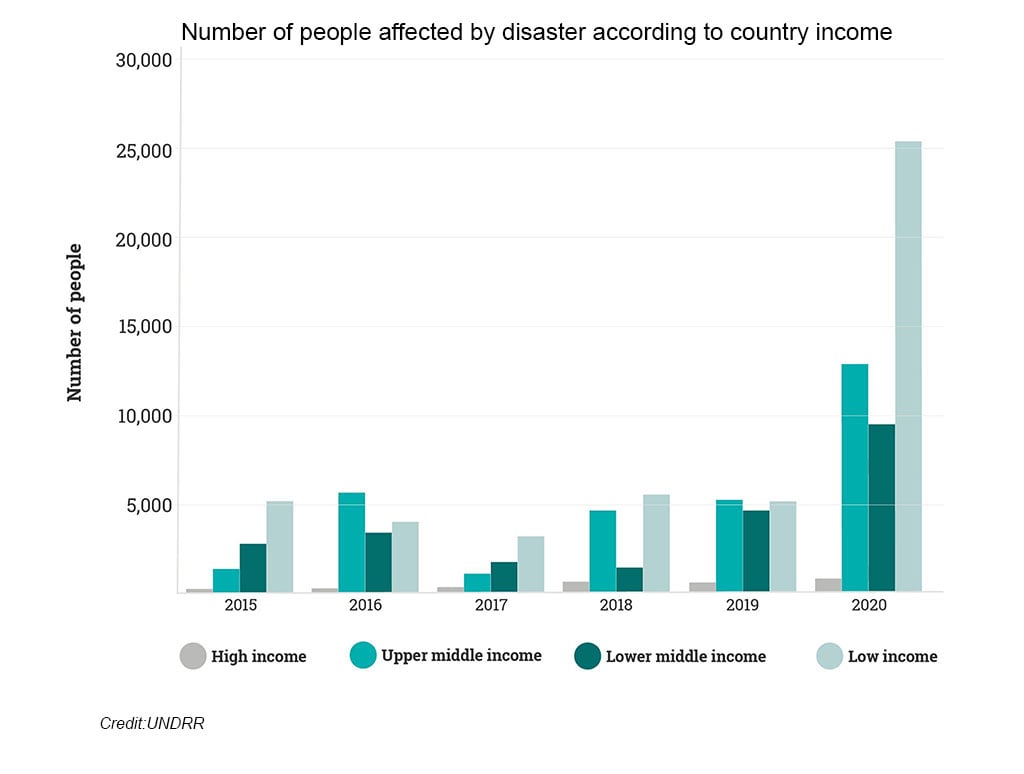

Although natural disasters, disease outbreaks, chemical accidents, and climate events can hit anywhere, they disproportionately impact the poorest. In the last decade, low- and middle-income economies lost, on average, roughly one percent of their GDPs, compared to only 0.1 to 0.2 percent for higher-income countries. The UN predicts that climate change impacts will push an additional 37.6 million to 100.7 million people into poverty by 2030, depending on global warming scenarios.

Our first case study of disaster neglect looks at a series of related events in Peru’s northern Amazonas region.

An estimated 13,000 people in a region known as the ceja de selva, or “jungle’s eyebrow” – due to its mountainous terrain above forested flatlands – found themselves facing aid shortages in the months after a 7.5-magnitude earthquake in late November 2021.

Initially, the quake, which killed two people, gained widespread national media attention. Peru’s embattled president, Pedro Castillo, visited and promised residents would be airlifted to safer locations. Lima’s newspapers covered the main events as they unfolded.

But even as one disaster then spawned several more, attention began to wane.

In December, intense seasonal rains provoked landslides in areas deforested for agriculture and weakened by the seismic activity. A flooded river washed away an ad hoc camp set up on its bank for earthquake survivors from another nearby community, killing one.

In the months since, at least eight more villages in the region have been destroyed by landslides and flooding. This includes, in early March, the village of Guayacán, where 90 hectares of land collapsed onto it from the hills above. Residents lost everything: their homes, their livelihoods, access to clean water, even their school.

Despite the growing difficulties, media coverage of the disaster area has dried up. As a political storm engulfed Castillo, the Amazonas crisis became largely forgotten outside the region. Assistance has all but disappeared. Some 2,000 people have now been living in tents for more than six months. And in the absence of more livable temporary housing, many families have returned to their homes and their land, in spite of the risk of more landslides.

Shock, anger, and impatience

Many people in the ceja de selva migrate from the Andes in search of better economic prospects. The communities they create reflect these roots architecturally, with wooden Andean balconies otherwise atypical in this jungle area. Settlers cut forests to plant banana trees and coffee, as well as genetically modified corn – replacing deep-rooted vegetation with new species that don’t retain the soil as well, facilitating erosion.

During a trip to the region in late April, The New Humanitarian spoke to survivors in four communities affected by the string of disasters. All said the promised government assistance was taking longer than expected to arrive.

Like many others, *María Nancy said she was still in shock and disbelief at what happened on 11 December when the hillside on which her village of San Isidro is perched began sliding downward.

“I had my house only for two years,” said the 49-year-old widow and mother-of-three, wiping tears from her face. “It was a dream to have this home.”

Four months on from the landslide, the devastation was still clear to see: Long and wide fissures crisscrossed San Isidro's few main roads, running both down and across the hillside, while the collapsed and dangerously cracked buildings remained eerily empty.

“I worked hard to have this and to raise my children well on my own,” María Nancy, who farms zebu cows for a living, said, standing in front of the skeleton of her former home. “At 3am, the house started filling with water, and I had to escape,” she recalled.

María Nancy refused to move herself or her 90-year-old mother into one of the tent clusters not far from their ruined home. She said the tents aren’t adapted for vulnerable populations, as they overheat in the tropical daytime and can’t be aired at night due to dengue-carrying mosquitoes. Worse still, they’re located in an area prone to landslides. Instead, they joined her brother in the temporary shelter he built on the plot of land he bought after the disaster.

“People [in the rest of Peru] don’t know what is happening here,” said Samuel, a day labourer in El Salao, another community affected by the earthquake. Residents there lost their homes and farmland after the mighty Utcubamba river overflowed when the earthquake caused its defences to rupture. “As humble people, who we are, we live in shame of our own conditions,” said Samuel. “Sometimes we’re afraid to go to the press to tell our stories. We have rights, but sometimes we are badly [informed about them].”

Frustrated by the slow pace of assistance, Samuel spent his savings on resettling into a newly built bamboo home a few hundred metres from the ruins of his old house – but in an area still next to the river and at risk from future flooding.

Allemant of Save the Children said heavier rainstorms due to climate change, coupled with deforestation, were leaving these communities at greater risk from landslides. “I have never seen people being displaced so many times,” she added.

Dependance and responsibilities

In late April, Allemant tried to encourage residents in San Isidro to move away from their landslide-prone homes to safer areas being set up for temporary resettlement.

However, there was strong resistance from residents who preferred to stay closer to their old homes and plantations. Many questioned whether the government would follow through with the necessary support.

Allemant tried assuring them. “We are committed to continue helping you after you resettle, to help mediate your discussions with local authorities,” she told the families.

Her organisation had supported more than 1,500 disaster survivors with cash transfers, water and sanitation facilities, and education support. World Vision and the Peruvian Red Cross also supplied food, cooking utensils, and fun distractions for children, while government response teams focused on setting up tent camps and health services.

This all sounds good, but emergency responders only want to be operating in such settings for a limited period. It’s then up to the Peruvian state – and the survivors themselves – to chart the longer-term path forward. “If not,” as Allemant explained it, “we are just reproducing a vicious cycle in humanitarian response.”

Felipe Pérez Detquizán, the regional director of Peru’s National Institute for Disaster Relief (Indesi), pushed back against criticism of the government’s operations in Amazonas, describing its response as “opportune, immediate, and adequate”.

Detquizán did acknowledge that resettlement to temporary homes had been slow, putting this down to difficulties in finding locations near enough to residents’ old homes that were also safe and affordable enough for the regional government. He added that COVID-19 had led to additional sanitation measures needing to be taken.

But this kind of explanation is unlikely to satisfy Jaime Quesquén, the director of San Isidro’s school – now housed in a temporary structure built by the residents themselves.

Quesquén was clearly annoyed by what he saw as insufficient support from the state. “We are fighting to get that assistance, and can say that it is because of us alone that our children are able to study here,” he said. “Right now, it is amazing to see that children in a republic like Peru require more of a presence by institutions that do not have anything to do with the state but which are ready to respond to our necessities.”

Worsening floods in Nepal also attract scant attention

The same kind of aid and media neglect that is afflicting disaster survivors in Peru is happening the world over. Take the recent flooding in Nepal, where communities struggle for attention partly due to the scale of the deadly storms and landslides in neighbouring countries.

Floods overan villages, towns, and cities throughout 2021’s monsoon season, taking the lives of 673 people while displacing 18,000. Unseasonal rains in October caused $50 million of damage as water swept away homes and roads, rice paddies, and bridges. And a single landslide in June 2021 blocked the Melamchi river and burst a dam in Bagmati province.

“Bangladesh has much more attention than say Nepal,” despite the countries being of similar geographical size, complained Azmat Ulla, head of Nepal’s delegation at the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). “Perhaps it’s to do with population density.”

Bangladesh’s population is nearly 168 million – 99,000 of whom were displaced following 31 disasters in 2021. Nepal’s population is 30 million, meaning that proportionally almost exactly the same amount of displacement occurred. Ulla suggested some of this misalignment in attention could be down to topography.

“[Bangladesh] is all flat, so when flood water gushes you can see flood water being stagnant and people walking in water at waist level – or even beyond that – and they’ll be sitting on their roof waiting for help,” Ulla said.

In contrast, he explained, Nepal's mountainous and glacial terrain is difficult to access and the impacts of climate change there are complex and often not clearly and widely explained. “Glacial bursts combined with monsoons in hilly regions… cause a lot of water outflow, washing villages [away], causing landslides and havoc to a lot of vulnerable communities.”

This, he added, could impact the level of awareness and subsequent aid: “If you don’t tell the story to the world, they’ll never know.”

Currently, there isn’t enough support for those affected by flooding, said Narayan Gyawali, Nepal programme director at Lutheran World Relief, which focuses on disaster assistance.

In 2008, international humanitarian funding for flooding in Nepal was $125 million. That has dropped to less than $25 million in recent years.

“The UN has done some [response] programmes on the disasters. That’s helpful, but it’s not enough,” Gyawali said. “We should work on the preparedness side more so we can make [people] aware [and] educate these people so they can go to safe places.”

While floods are not new to Nepal, the country “is not necessarily prepared to deal with the major natural disasters occurring in a multi-hazard environment, such as extreme rainfall that carries a lot of sediment or a landslide that blocks a river,” noted Dr. Santosh Nepal, researcher of water resources and climate change at the International Water Management Institute.

There is a growing understanding of how floods are happening in the country, said Nepal, but the next step is to share flood forecasting information in a more meaningful way so that communities understand the potential risk and take necessary precautions.

Too many crises, too little funding

The UN’s emergency aid coordination body, OCHA, doesn’t have a classification for forgotten disasters, but the UN's Financial Tracking Service does highlight the disparities in global pledges: Nearly 50 percent of all emergency funding this year is going to only five protracted – and largely conflict-driven – crises.

Florent Del Pinto, emergency operations chief at the IFRC, described the proportion of funding going to lesser-known emergencies as “a concern”. “There is a headline around climate change on the global stage, but there are not many headlines toward the small emergency operations that are really linked globally to climate issues,” he said.

IFRC’s own Disaster Response Emergency Fund (DREF) specifically targets lesser-known global disasters. Of the $30-40 million in funding raised annually for the DREF, Del Pinto said the events in Peru’s Amazonas were “particularly under the radar”, leading to the organisation’s decision to allocate $250,000 towards distributing blankets, building tools, food, psychosocial support, water and sanitation, and hygiene kits.

The Red Cross would generally assist disaster-affected populations for “not more than six months” before handing over to local authorities and communities, Del Pinto said, conceding that states sometimes “do not stand up” to fulfil their role. DREF funding, meanwhile, also has its limitations. For example, in Amazonas, Del Pinto explained, “we don’t have [enough] money to facilitate a smooth transition or recovery or even development.”

Breaking the cycle

Given both rising climate change risks and improved technological abilities to forecast disasters, there have been growing calls for more anticipatory action and financing, including most recently by the G7 group of industrialised countries.

Ricardo Mena, UNDRR’s director, told The New Humanitarian that while losses could be mitigated through better disaster risk reduction strategies, “only $5 of every $100 spent in aid related to humanitarian assistance goes towards disaster risk reduction measures.”

This includes building earthquake-resistant houses, better drainage systems, and structures adapted to how a changing climate impacts different environments.

“We are trying to ensure that disaster risk reduction is not only seen as an issue that has to be taken up by the development actors, but also by the humanitarian community,” Mena told The New Humanitarian. “When you don’t use the possibility of the recovery process to build back better and ensure that you infuse a stronger resilience into communities, then you are potentially repeating the same cycle of disaster-response-recover-repeat.”

Mena said UNDRR is working with OCHA to provide better guidance on how to incorporate disaster risk reduction into humanitarian programming.

This may not be fast enough for survivors of the events in Amazonas who are taking their lives into their own hands by remaining where they are as they await assistance. Many feel forgotten, and the future is scary.

In El Salao, Samuel, who works in the low-lying rice fields nearby, explained that he and his family are hoping that new reinforcements are built along the river to avoid further flooding, and possibly the destruction of their new home. They keep a close eye on the river, returning to the emergency tented camp whenever water levels rise.

“These events haven’t been silent for us,” he said. “We are still very worried.”

* First names only have been used for vulnerable disaster victims.

Transport was provided to The New Humanitarian by Save the Children. Additional reporting by Rebecca Root in Bangkok. Edited by Abby Seiff and Andrew Gully.