Towards the end of May, Ali Jinnah Hussin, 20, noticed that a lot of people in the Balukhali Rohingya refugee camp in Bangladesh where he has been living since 2017 were starting to fall sick.

“Most of the people… are getting the symptoms of COVID-19,” Hussin told The New Humanitarian by phone. “In the area where I am living, there are 100 other families. In one of them, 75 or 85 of the family [members] were getting sick, flu, cough.”

More than 900,000 Rohingya refugees who fled neighbouring Myanmar live in camps in the largest refugee settlement in the world, close to Cox’s Bazar in southeast Bangladesh.

Until recently, the number of COVID-19 cases had remained low. But as a devastating second wave of infections has swept across South Asia in the past month – pushing healthcare infrastructure to the brink and sending death tolls soaring – case numbers have also been rising in Bangladesh and in the camps in Cox’s Bazar.

Of the more than 1,350 COVID-19 cases recorded in the Rohingya camps since the beginning of the pandemic, half have come in the past month. The true tally is undoubtedly much higher, but limited testing means many infections are never officially counted.

With little other than lockdown measures standing in the way of a large-scale outbreak, the uptick in transmission in the Rohingya camps is highlighting the danger the pandemic continues to pose to refugees and other displaced people around the world, underscoring the urgency of including these populations in COVID-19 vaccination campaigns.

As of the end of May, at least 54 countries have started vaccinating refugees, according to data shared with The New Humanitarian by the UN’s refugee agency. Out of 157 countries UNHCR is monitoring, 150 have said publicly or privately that they will include refugees in their inoculation campaigns.

But so far, “the main thing that is actually stopping equitable access to vaccines [for refugees] is the global supply,” Ann Burton, chief of UNHCR’s public health section, told The New Humanitarian.

Around 85 percent of vaccines already administered have gone to people in high-income and upper-middle-income countries, while 85 percent of the 26 million refugees in the world are hosted in developing countries.

Due to a number of factors – export bans in countries such as India; a global shortage of raw materials used to produce vaccines; and hoarding by wealthy nations – COVAX, a UN-backed global initiative to ensure equitable COVID-19 vaccine access, will have distributed around 190 million fewer doses than anticipated by the end of June.

A donor summit hosted by Japan at the beginning of June secured pledges for an additional 54 million doses and $2.4 billion in funding for COVAX, and the United States released details of a plan to send 80 million vaccine doses around the world – mostly through COVAX – by the end of the month. Experts say these are steps in the right direction, but much more needs to be done to close the gap in access.

When supplies do eventually catch up, experts say many refugees and displaced people still risk not being vaccinated because of: design oversights in national vaccine registration systems; the logistical challenges of reaching people in remote areas and conflict zones; and the compounding issues of vaccine hesitancy, misinformation, lack of trust in authorities, and pre-existing social marginalisation.

Limited supply

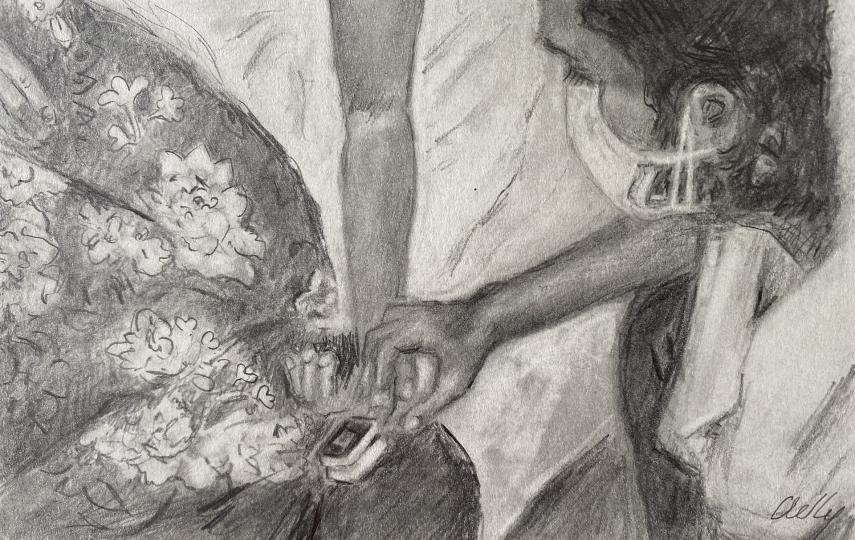

In Bangladesh, as of 1 June, not a single vaccine dose had been administered in the camps in Cox’s Bazar, despite earlier pledges by the government to include refugees in the rollout.

“As far as I know, it is very important for the people to take vaccination inside the camps,” Hussin said. “These camps are very, very crowded. If someone got COVID-19 positive, then it is easy to spread anywhere.

“That’s why I think all humanitarian organisations and government agencies need to try to give vaccination across the camp,” Hussin added.

Around 11 million doses of the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine allotted to Bangladesh through COVAX, including 130,000 earmarked for Rohingya in the camps, were supposed to arrive by May, but because of India’s export ban – the doses were supposed to be manufactured in India – the vaccines never arrived.

Plans to start vaccinating Rohingya were put on hold, and after administering close to 10 million AstraZeneca doses procured outside the COVAX programme, Bangladesh essentially ran out of vaccines at the end of May.

The government has since secured additional supplies, but not enough to make up for the shortfall, and Bangladesh is far from the only refugee-hosting country largely relying on COVAX for its vaccine supply to be hit by the programme’s procurement shortages. Uganda, Pakistan, Lebanon, and Colombia host some of the largest refugee populations in the world. All have received only a fraction of the vaccine doses allotted to them through COVAX.

The limited supply doesn’t only affect refugees. Without enough doses, healthcare workers, the elderly, and high-risk people are also not getting vaccinated, regardless of their nationality or immigration status.

On the back of the supply problems, governments that have said they will vaccinate refugees might not follow through when forced to choose who should be prioritised to receive the small number of available shots, according to Paul Spiegel, director of the Center for Humanitarian Health at Johns Hopkins University in the United States.

“I think it’s positive that [refugees] are being included,” Spiegel said. “But it’s easier to write that down than actually do it, and I believe that will still remain a challenge because of limited vaccines.”

Other barriers

Shortfalls aside, the ability for refugees, displaced people, and migrants of any type to get vaccinated in many countries comes down to whether they have the identification documents accepted by government registration systems, according to Belkis Wille, a senior researcher in the crisis and conflict division at Human Rights Watch (HRW).

“If the registration system that the government has established requires a certain type of identity card that refugees don't have access to, or that other migrants don't have access to, they will be de facto left out of the vaccine campaign regardless of what the government said in its plan,” Wille said.

“Will refugees – many of whom are already discriminated against and don't trust authority – be willing to accept this vaccine?”

There’s quite a long list of other barriers preventing refugees from having equitable access, said Ezekiel Simperingham, global lead for migration and displacement at the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). This list includes: the cost of vaccination – if it’s not being provided for free by host countries; language barriers that prevent refugees from accessing reliable information about vaccines and how to get vaccinated; and the absence of the digital literacy needed to navigate online registration portals used in many places to coordinate vaccine appointments.

Inoculating refugees, displaced people, and other vulnerable populations in conflict zones and areas outside the reach of government programmes in places like parts of Yemen and Somalia poses another challenge. COVAX has set up a humanitarian buffer that is supposed to fill this gap, but it has yet to launch.

Another important issue is trust, according to Spiegel. “Will refugees – many of whom are already discriminated against and don’t trust authority – will they be willing to accept this vaccine?” he said. “That’s going to depend a lot on very strong communication.”

In Lebanon, for example, refugees theoretically have the same access to vaccines as Lebanese, but their vaccination rates are lagging far behind.

Around 1.5 million documented and undocumented Syrian refuguees live in Lebanon – about 25 percent of the country’s population. But as of 7 June, only 7,888 of the nearly 875,000 vaccine doses administered have gone to Syrians. The reasons are layered.

For years, Lebanese authorities have adopted policies making it difficult for Syrians in the country to maintain legal residency, access basic services, and earn a living. Lebanese politicians regularly talk about sending refugees back to Syria and have forcibly deported thousands.

According to an HRW report, despite assurances that data will be firewalled from security agencies, many Syrians fear registering on the government’s vaccine platform could lead to arrest, detention, or even deportation – a fear that’s shared by people with precarious immigration statuses in other countries as well.

Some Syrian refugees are psychologically exhausted from the consequences of years of hostile policies compounded by the effects of the pandemic and overlapping economic and political crises in Lebanon, according to Fatema Fakhourji, a 23-year-old Syrian living in Beirut with her family.

“I heard from many people that they don’t care if they die anymore,” Fakhourji told The New Humanitarian.

Against this backdrop, generating interest in vaccination is a daunting task, but Fakhourji said not enough is being done to raise awareness about the importance of being inoculated among refugees, or to combat vaccine hesitancy stemming from the rampant spread of misinformation.

“Let’s talk honestly, UNHCR and NGOs… don’t have any plan to face this misleading and fake information,” Fakhourji told The New Humanitarian.

UNHCR Lebanon is working with teams of refugee volunteers to spread awareness about the importance of getting vaccinated and combat misinformation.

At close to four million, Turkey hosts the largest population of refugees and asylum seekers in the world. Around 3.6 million are Syrians who fled the civil war in their country by crossing Turkey’s southern border.

Home to around 84 million people, Turkey is an upper-middle income country and is not relying on COVAX for its vaccine supplies. So far, health workers have administered over 30 million vaccines, enough for 21 percent of the population to receive at least one dose and 16 percent to be fully vaccinated. In comparison, only 8.2 percent of Lebanon’s population has received at one dose and 4.2 percent is fully vaccinated.

Like Lebanon, on paper, refugees in Turkey have the same access to vaccines as nationals. “If you have an ID… and you are [in the priority group for] vaccination, you will be able to take the vaccine,” Kinda Alhourani, a Syrian doctor who has been living in Turkey since 2014, told The New Humanitarian.

However, if a refugee or asylum seeker is undocumented or doesn’t have they necessary ID, they won’t be able to register in the government system, Alhourani added.

Also, as of March, around 50 percent of Syrians in Turkey were hesitant to get vaccinated, according to a survey conducted by the IFRC.

“Unfortunately… they don’t believe that they should take the vaccine,” Alhourani said. “They still believe that it’s a global conspiracy, and they don’t trust the process of creating the vaccine.”

Language is a major barrier because information being disseminated to combat misinformation and the registration process to get vaccinated are both in Turkish, Alhourani explained.

“So, we need some kind of outreach campaigns,” she continued. “But with the bureaucracy here inside the ministries and the kinds of permissions and protocols… it’s very hard to have the permission to do outreach activities.”

Across Turkey’s southern border, in northwest Syria – one of the few areas of the country still controlled by groups opposed to the Syrian government – around 54,000 vaccine doses have been delivered through COVAX.

Vaccine hesitancy in northwest Syria is also high, and it is compounded by the dire humanitarian situation in the region, where about 2.7 million people displaced by the war live, according to Alhourani, who works for an NGO called the Syrian Expatriate Medical Association (SEMA), which runs three COVID hospitals in the area.

However, there are widespread advocacy campaigns underway to convince people to take the vaccine, which is currently only available to frontline medical workers, to make sure doses don’t go to waste. “We have armies of health staff and social workers [doing] advocacy,” Alhourani said.

India’s export ban has delayed the delivery of further vaccine doses to northwest Syria through COVAX.

Fakhourji’s father registered to be vaccinated and received his first dose in April, but many other Syrians – even those who understand the importance of getting a jab – are afraid of the side-effects, especially following reports of rare blood clots linked to the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine in a small number of cases. If something goes wrong, Syrians in Lebanon worry they won’t be able to access healthcare, Fakhourji said.

“We’re not secure,” she added. “We don't have any insurance to cover the hospital expenses. We don’t have appropriate healthcare.”

‘If they can value the vaccine in money…’

For some refugees – many of whom have been disproportionately affected by the negative economic impacts of the pandemic – the international community’s focus on the importance of inoculation can come across as tone deaf to their other pressing daily needs.

“If we are to ask refugees what do they really want for now, many people will tell you, ‘Buy me food and pay rent,’” Joyeux Mugisho, a Congolese refugee living in Kampala, Uganda, told The New Humanitarian.

“They wouldn't choose to get the vaccine,” Mugisho, the executive director of a refugee-led organisation called People for Peace and Defense of Rights (PPDR), continued. “If they can value the vaccine in money, they will choose the money to survive rather than getting the vaccine.”

“Why do you care about me getting a vaccine when you're not caring about my children’s food, or education, or… shelter?”

Uganda hosts around 1.4 million refugees and is in the midst of a second wave of COVID infections. Due to limited supplies, less than one percent of the around 44 million people living in the country has been fully vaccinated.

In Kampala, refugees are still reeling from the first wave of the pandemic, according to Mugisho. Since last March, many haven’t been able to work, and a transportation ban during the first wave last year made it difficult to access medical care and other basic services.

“We’ve seen families going days without eating,” Mugisho said. “We’ve seen [refugees] losing their lives because of not having access to medical care or even having transport to reach the hospital.”

Parwana Amiri, a 17-year-old from Afghanistan, has been living in Ritsona refugee camp outside Athens, Greece since the beginning of 2020. In April this year, her mother came down with symptoms of COVID-19 and then her father. Social distancing wasn’t possible in the housing unit they shared in the camp and, one by one, Amiri and each of her family members – except for two siblings – contracted the virus.

“When you would come to see our house, we were all in the beds. We were not able to move. It was really serious,” Amiri told The New Humanitarian.

Amiri’s brother ended up having to go to the hospital, but there were no translators to help him communicate when he arrived by ambulance. Amiri’s family also did not receive support from doctors or medical staff while they stayed isolated in their accommodation in the camp until they recovered, she said.

Greece started administering COVID vaccines at the end of December last year. But, despite concern about the possibility of outbreaks in crowded, often poorly serviced refugee camps, only began rolling out a large-scale vaccination campaign for the around 60,000 refugees and asylum seekers currently living in the facilities and other government accommodation at the beginning of June.

However, interest in getting vaccinated among refugees in Greece is also reportedly low. In large part, the hesitancy is due to the spread of misinformation, according to Amiri. “They are afraid of having the side-effects,” she said.

At the beginning of the pandemic, NGOs and government health officials were raising awareness in the camp about the dangers of COVID-19 and how people could protect themselves, but a similar effort is not being made to educate people about the vaccine, Amiri continued.

After her family’s experience, Amiri added: “I think it is really important [to get vaccinated] because we live in the camp and if somebody gets sick it will be really dangerous because people who are living here, most of them are vulnerable; they have serious medical problems.”

Ugandan authorities have administered a small number of vaccines to South Sudanese refugees living in a camp in the northwest of the country, but questions of inclusion and access are largely theoretical until more supplies arrive.

Still, Mugisho said authorities are behind the curve when it comes to informing refugees about the importance of getting vaccinated. “Some are very negative about the vaccine because they have no information about it,” he explained.

Others wonder where authorities, the international community, and NGOs have been for the past 15 months while refugees have been struggling.

“That’s part of… why people are very reluctant when they hear the word vaccine,” Mugisho said. “When I was starving, you were not there, or when I was being evicted from the house, you were not there. Why do you care about me getting a vaccine when you're not caring about my children’s food, or education, or… shelter?”

To overcome that frustration and hesitation “you have to work with the communities to understand better what their concerns are and how they’re actually prioritising these,” said Burton, from UNHCR.

“Make it as easy as possible for people to get vaccines,” she added. “If you bring the vaccine as close as possible to people so there’s no opportunity cost for them getting vaccinated, that will certainly help.”

Refugee-led organisations could play an important role in the effort to drum up interest, according to Mugisho.

“I think the pandemic was very important for the humanitarian world to see the role of refugee organisations,” he said. “We are supposed to be involved in this campaign... so that we can know how to sensitise the communities and the masses to come and get this vaccine.”

For now, while much of the world is still waiting on supplies, it’s important to be pushing for equitable access to vaccines both between and within counties, Simperingham, from IFRC, told The New Humanitarian.

“If only some countries are vaccinated, it won’t have the global impact that we hoped for,” Simperingham said. “But even within a country… it’s just so important to make sure that we don’t leave anyone behind, that pre-existing prejudice or discrimination or marginalisation doesn’t manifest in vaccine campaigns; because ultimately it will be self-defeating.”

er/ag