When she was certain the gunfire had stopped, Ana Teresa Castillo helped up the children she had been shielding with her body.

They had been crossing an illicit trail linking Colombia and Venezuela when a shootout erupted between armed criminal gangs vying for control of the lucrative smuggling route.

The group hurried the rest of the way into Colombia, a 10-minute walk away. Castillo brought the children safely to her home. It was only then she noticed they had defecated themselves.

These weren’t Castillo’s children – just three of the hundreds of unattended kids and thousands of adults who cross every day from San Antonio, Venezuela into La Parada, Colombia via the illegal routes known as trochas in search of food, work, medical attention, or schooling.

“Who lets their children cross the trochas alone?” asked Castillo, speaking to The New Humanitarian in the small shelter for women she runs out of her home in the borderland neighbourhood. “I couldn’t just leave them there.”

Fearing for their personal safety or seeking employment abroad, Venezuelans have been fleeing their collapsing nation for years. Inflation has risen 3,012 percent in the past year alone, and healthcare, education, and employment have all but disappeared. Escalating conflicts in the border state of Apure between the Venezuelan military and leftist Colombian armed groups displaced at least 6,000 people in March and may also be adding to the flow of refugees.

For those who feel they have no choice but to brave the journey out of Venezuela, these kinds of illegal paths are increasingly the only option.

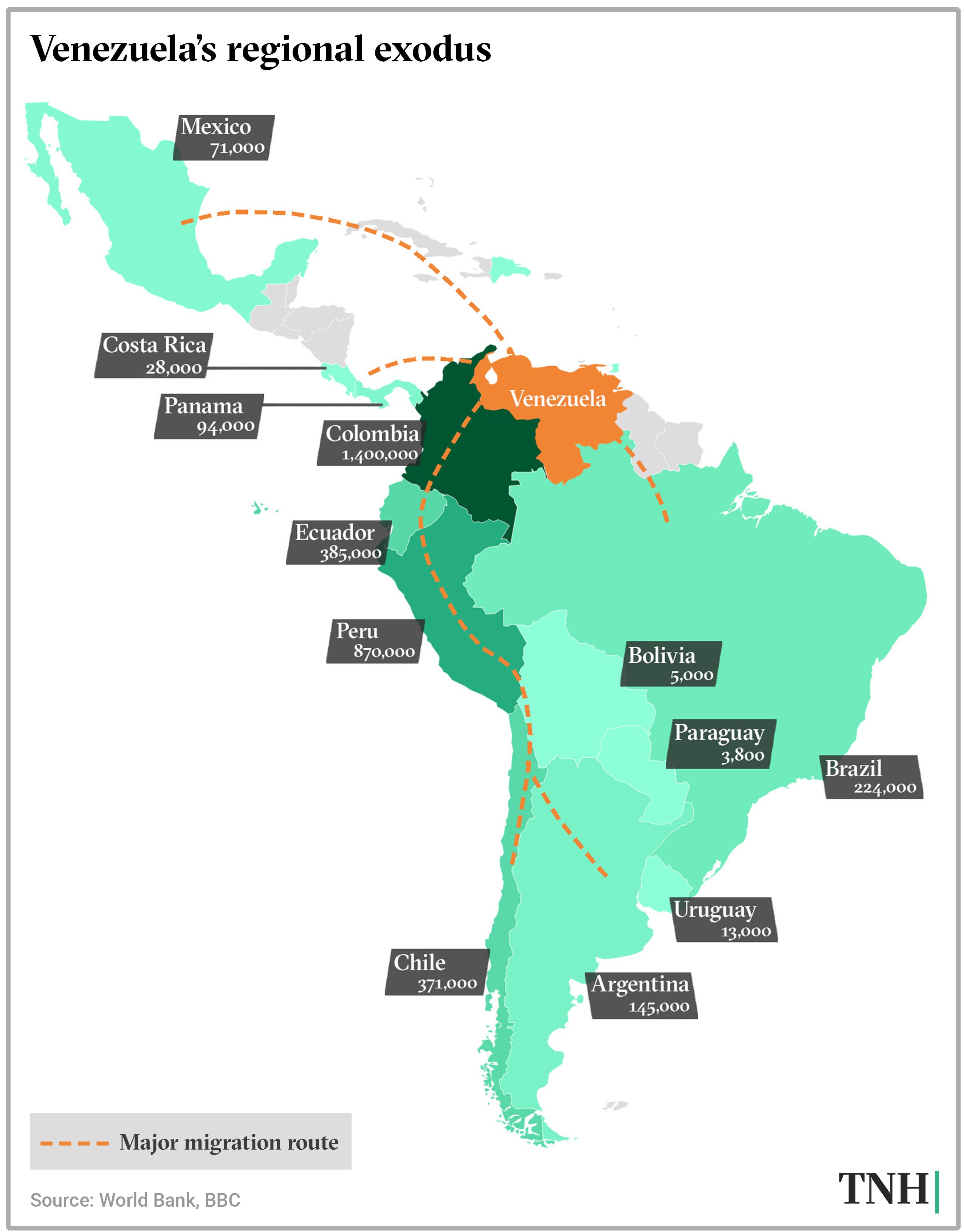

A year into the pandemic, as South American countries continue to reel from second and third waves of infections, land borders in Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Chile, and Bolivia remain officially closed. Many are heavily militarised, leaving desperate Venezuelans forced to cross a continent along dangerous frontier routes controlled by criminals.

‘If I don’t cross, my family doesn’t eat’

March 15th marked the one-year anniversary of the closure of the Colombian-Venezuelan border due to COVID-19. Since then, the situation on the already violent frontier has worsened.

2020 was a deadly year for Cúcuta, the capital city of the department of Norte de Santander, of which La Parada is a suburb. Last year, the region registered 238 violent deaths – a 30 percent increase over 2019.

Castillo and other residents who live in La Parada say the true figure is far higher. They say a great many killings go unreported due to fear of reprisals from the armed groups that battle over the lucrative extortion and smuggling territory.

On the Venezuelan side of the border, the lawlessness is even worse. The government no longer releases crime statistics, but Fundaredes, a nonprofit that tracks violence along the border, reported 1,619 homicides in the departments along the 2,219-kilometre frontier in 2020 – a 40 percent increase over the previous year.

Francisco Rivas makes a living buying electronics and consumer goods in Cúcuta that he then resells in Venezuela. He was exiting the trochas when The New Humanitarian visited. He seemed unconcerned by the presence of nearby police. “Hunger is stronger than border policy,” he said. “It’s stronger than fear of COVID, too. These people have no choice,” he continued.

“And neither do I. If I don’t cross, my family doesn’t eat.”

Hard figures are unknown, but Víctor Bautista, the secretary of the Department of Borders and International Cooperation in Cúcuta, estimated at a press conference in February that 5,000-7,000 people were still crossing daily near that border city alone.

“Despite the border closure, this movement has never stopped,” he said. “It’s impossible for immigration to [stop] it completely.”

The situation on the Venezuelan-Colombian border reflects a broader trend regionally.

The numbers of migrants crossing into Chile via Bolivia has increased as well – a route largely unused by Venezuelans before the pandemic. Chilean officials estimate that 200 people are now entering the country each day through a dangerous and remote high-desert region near Colchane on the Bolivian-Chilean border in order to avoid the military stationed along Chile’s northern border. At least two people are known to have died, though the real toll is likely far higher.

Amnesty International has warned that militarised borders in Peru are also putting migrants at risk, stating in a January report that: “The use of military personnel for border control work presents a grave risk to the human rights of migrants and refugees, due to the lack of training and adequate tools for such a role.” Militarised borders also displace migrant entries to more dangerous and remote points, according to the Norwegian Refugee Council.

Some 5.6 million Venezuelan refugees have fled their country since 2015, with Colombia, Peru, and Chile supporting the largest shares respectively, according to the UN’s refugee agency, UNHCR, which has predicted that the diaspora could reach seven million by the end of 2021.

While COVID-19-related restrictions have changed the patterns of movement, they haven’t stopped the migrant flow. Approximately one million Venezuelans left their country between November 2019 and March 2021.

Voices from the border

The migration crisis is “arguably the greatest humanitarian challenge that Latin America and the Caribbean is facing today”, World Bank regional vice president Carlos Felipe Jaramillo said in an 11 May panel discussion, appealing for greater international support. Funding for the Syrian emergency, the world’s only larger refugee or migrant crisis, has been more than 10 times higher, he pointed out, and needs related to Venezuela’s exodus will only continue to grow.

Experts have suggested that when land borders re-open, the numbers crossing may rise significantly. Colombia’s migration department has announced it will re-open its border with Venezuela on 1 July. Venezuelan President Nícolas Maduro, in recent public comments, called the decision a “show”, but said he will consult with governors in the border region to determine whether it is safe to reciprocate the Colombian move.

Read more → Colombian protests: Poverty and the pandemic collide with conflict and migration

Colombia is struggling with a new wave of COVID-19, reaching a record 530 deaths on 16 May and nearly 19,000 infections, and facing a seven-day average of 482 daily deaths. Its coronavirus crisis has been compounded by weeks of anti-government demonstrations that have drawn thousands onto the streets, protesting rising inequality amid the pandemic. These have been met with violence, with at least 40 people killed by police.

Government claims that the protests are partly the fault of Venezuelan infiltrators – an accusation made without proof – may also be driving increased xenophobia towards migrants.

In the hands of criminals

With large numbers of migrants continuing to move, and borders now militarised, the situation presents a golden opportunity for those who smuggle people across the border, as well as the armed groups who control illicit crossings throughout South America.

“Jo-Jo”, who asked for his name to be withheld for security reasons, is a smuggler based in La Parada. He sells passage not just across the Colombian-Venezuelan border, but also across every closed border from Caracas to Argentina, and all points in-between.

He prefers the term asesor (consultant) to the more informal coyote (smuggler), and when he talks of work it is in the manner of a polished salesman. He refers to his network as a travel agency, and to the employees he has scattered across the region as “agents”. He says his network monitors clients via WhatsApp throughout the entirety of their long trips, troubleshooting in real time any potential problems they may encounter with immigration officials or with the criminal groups who control the illegal paths they must cross.

“We have contacts with them all. Usually they just want ‘taxes’ for letting us operate,” he said, clarifying that he was referring to criminal groups and immigration officials alike, across multiple borders. “Within the illegality, my business is legal, in that I look after my clients,” said Jo-Jo. “I have a reputation to maintain if I want to keep attracting clients.”

Jo-Jo may weave a tale of security and safety as he talks of his business, but statistics as well as the stories of migrants who spoke to The New Humanitarian belie his claims.

In a December report, the International Crisis Group documented killings, forced sex work and recruitment, child recruitment, and sexual assaults at the hands of armed groups along the Venezuela-Colombia border.

Castillo’s shelter offers counselling for victims of gender-based violence and sexual assault, and she has no shortage of women in need of help. “We see a lot of violence against women in the trochas, from sexual assault, to robbery, to murder,” she said.

“Within the illegality, my business is legal, in that I look after my clients,” said Jo-Jo. “I have a reputation to maintain if I want to keep attracting clients.”

One migrant woman, who asked that her name not be used for fear of retaliation, described being robbed by one of the smugglers. She, her husband, her children, and her elderly mother spent their savings on what was supposed to be safe passage across the 680 kilometres between Portuguesa, Venezuela and Ríohacha, a northern coastal town in Colombia.

“We thought we bought passage for the whole trip, but it was a scam,” she said, speaking from the side of the road in the mountains a few hours from Cúcuta. “They took everything we had. And now we’ll have to walk or beg for rides.”

Pandemic brings fear and hardship

Colombia recently granted 10-year residency and the right to work to all Venezuelan migrants who enter the country legally, and the Ministry of Health has announced that immigrants will receive vaccination for coronavirus as well. But with limited resources, receiving nations have shown mixed responses. Peru has tightened immigration and work restrictions for Venezuelans, while Ecuador has seen public demonstrations against Venezuelan immigration as well as forced evictions of migrants.

The arrival of COVID-19 has also led to more and more accounts of xenophobia against migrants across the region, as some media reports and politicians have increasingly blamed them for crime, unemployment, and disease.

None of these claims have been made with evidence, and research by the Brookings Institute actually suggests the opposite is true. Not only are migrants more likely to be the victims of crime than the perpetrators, but also the influx of Venezuelan migrants has created a net positive effect on their host countries by nearly every measurable metric.

“The vast majority of Venezuelans in all host countries are law-abiding, and migration as a whole benefits the economies of host countries,” said UNHCR’s Latin America spokesperson, William Spindler. “But we have seen some politicians, across the entire region, trying to make Venezuelan migrants into scapegoats for their own internal problems.”

Some observers have even described the migrationary wave as “supercharging” local economies. But that hasn’t stopped some local communities from blaming them anyway for economic and health woes in Latin America, which lags behind the rest of the world considerably in vaccination rates, and represents a disproportionate amount of COVID-19 deaths.

But for migrants like 56-year-old Henry Ramírez, who had made his way from Caracas to a shelter near Cúcuta set up for those crossing on foot, no barrier on migration – legal, physical, or social – could compete with his drive to care for his loved ones.

“This is a list of medicines I need to send to my family,” Ramírez told The New Humanitarian, brandishing his inventory. “This is my mission. Once I’ve got work, this is the first thing I am doing.

“If I don’t,” he continued, “people I love are going to die.”

Additional reporting provided by Richard McColl.

jc/as/ag