Less than five years after landmark peace accords intended to usher in a new era of stability in Colombia, the country is gripped by deadly street protests that began over a tax reform but quickly spiralled into broader outrage at state neglect, COVID-19 fallout, and police brutality.

The protests, which have claimed dozens of lives since the end of April, come as renewed conflict is displacing poor and Indigenous communities, Venezuelan refugees continue to stream into the country, and the pandemic has pushed 3.6 million more Colombians into poverty.

Gimena Sánchez-Garzoli, Andes director at the Washington Office for Latin America (WOLA) think tank, said the demonstrations are a continuation of a movement launched in late 2019 by those who feel left behind by conservative President Iván Duque’s new administration.

They are angered, she said, by its “complete inability to show any empathy, care, or concern for the majority of Colombians in the country, and [by] the rising insecurity, displacement, humanitarian situations, massacres, and killings of social leaders, which are integrally related to the Duque government's efforts to undermine the peace process”.

The 2016 peace accords included promises to address rural inequalities and social development, but the Duque government has cut funding for their implementation since his administration came to power in 2018 campaigning on dismantling the agreement.

The 2019 protest movement was thwarted by pandemic lockdowns last year but has been re-ignited now against the backdrop of even greater economic fallout as well as the country’s deadliest peak of COVID-19, with many intensive care units nearing or exceeding capacity.

On 28 April, thousands of Colombians across the country took to the streets to protest a controversial tax reform plan, which many felt unfairly burdened the working class with tax hikes on basic goods. As the protests have raged for the 13 days since, they have broadened, grown bloodier, and show no signs of stopping.

The Colombian ombudsman’s office has reported 19 deaths, although many NGOs are reporting more. Rights groups Temblores and Indepaz jointly counted 39 alleged police killings, over 900 arbitrary detentions, and 12 sexual assaults allegedly committed by police. The police have reported 800 injuries to their own personnel and at least one death.

Nomadesc, a human rights organisation based in the western city of Cali, where much of the violence has taken place, estimated 28 deaths in the Cali region alone – a disproportionate number of them Afro-Colombian. Road blockages, meanwhile, have caused fuel and food shortages. And on Sunday at least six Indigenous protesters were shot at and injured in a clash with armed residents that was condemned by the UN’s human rights office.

On 2 May, Duque withdrew the tax bill and the country's finance minister announced his resignation – concessions to protesters rarely seen from this administration. But by Sunday night, a week later – and despite condemning certain acts of police violence – the president had deployed military forces to help quash the demonstrations in several cities and told the Indigenous ‘minga’ protest group to “go back to their reservations”.

Feeling the COVID-19 pinch

Colombia, like many of its neighbours, has been hard hit by COVID-19, and is facing a ballooning deficit and debt crisis as the government struggles to continue paying for the handouts and social programmes it has put in place during the pandemic.

As lockdown restrictions have shut down businesses, closed schools, disrupted markets, and sent an ascendant middle class back into poverty, distrust in institutions has surged among a public already vexed by a worsening security situation.

Since 2016, the dismantling of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia guerrilla group, known as FARC, has left behind a power vacuum into which other armed groups have stepped in, wrestling for control in former FARC territory. Meanwhile, several high-ranking FARC dissidents, including Iván Márquez, have taken up arms again. Both FARC dissidents and the ELN, now the main leftist guerrilla group, have expanded into Venezuela, leading to clashes with the Venezuelan military that sent thousands of refugees streaming into Colombia in March.

“You have the feeling that rulers somehow govern thinking about an imaginary country.”

In 2019, the protests were mostly centred on the big cities, but this time around protests have also been widespread in rural areas and small towns – motivated in part by the lagging implementation of aspects of the peace agreement, including land ownership reforms and coca crop substitution programmes that are crucial to farming communities.

Vivian Villafaña, a 23-year old student studying political science at Bogotá’s Javeriana University, said she joined marches in the capital on 8 May after initially taking part in protests in her hometown of Santa Marta, where she has been studying remotely. She said the beachside town of roughly 500,000 has seen many residents turn to selling fruit on the street as the tourism industry on which they depend has been decimated.

Villafaña, like several other protesters who spoke with The New Humanitarian, cited former finance minister Alberto Carrasquilla’s recent remarks that a dozen eggs cost 1,800 pesos (about $0.50) when they often cost four times more as an example of the profound disconnect between the government and the daily struggles of its citizens.

“You have the feeling that rulers somehow govern thinking about an imaginary country,” she said. “And that that imaginary country that they have does not correspond to the country’s reality at all.”

Villafaña said she also went out to protest in Santa Marta because the murders of many Indigenous social leaders affected her personally as an Indigenous Aruhuaco Colombian.

“I know close relatives who have lived their entire lives defending the land, defending the environment,” she said. “And they have already been threatened more than once.”

Elsewhere, in the northeastern region of La Guajira, members of the Indigenous Wayuu community joined to demonstrate against government neglect amid mounting hunger and poverty. The Wayuu have long called for more federal support for a region facing a collapsing health system, informal encampments of Venezuelan refugees, and spiking violence.

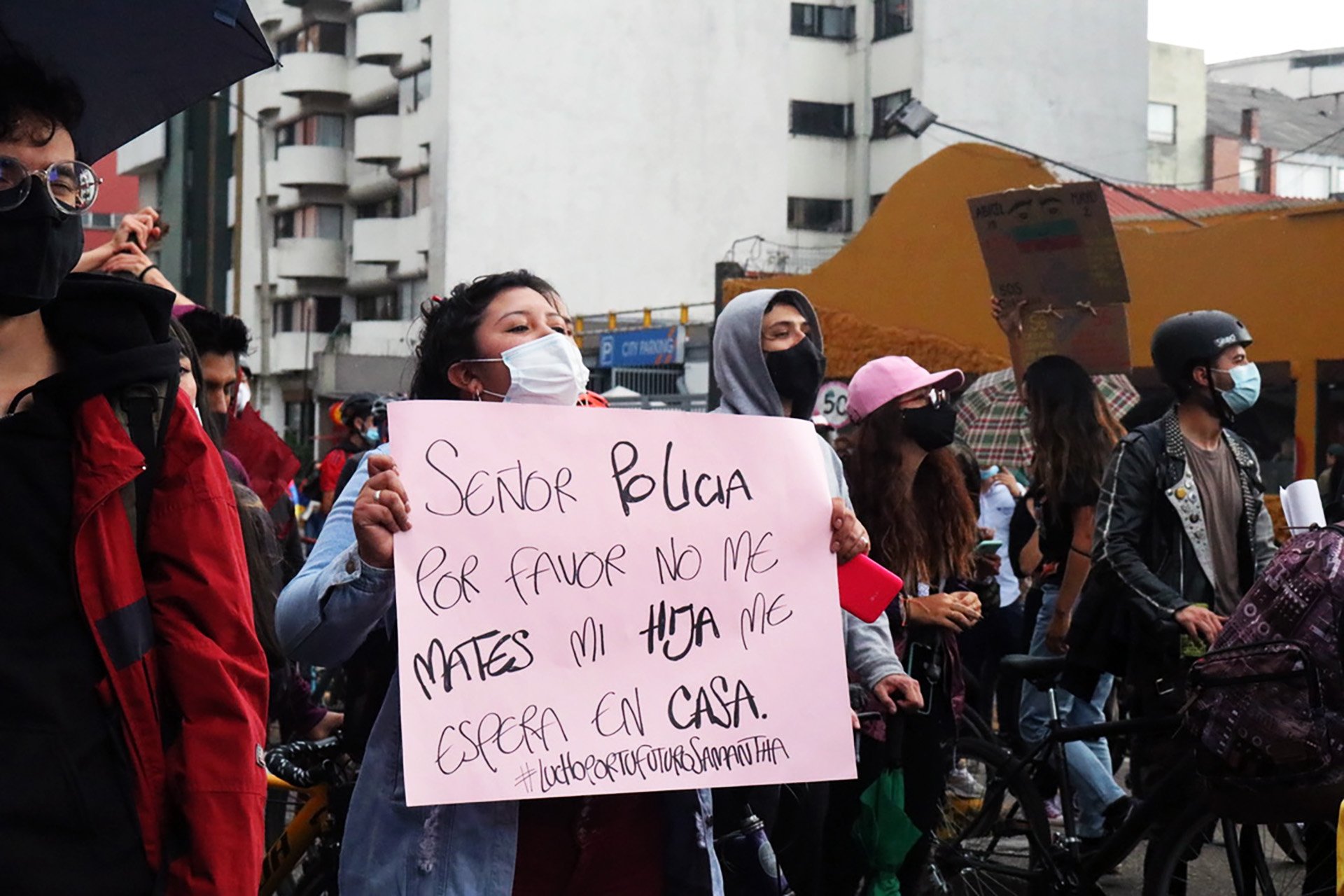

Police brutality

The response to the popular discontent has been brutal. Police have carried out attacks at night-time, often cutting off electricity and blocking social media to cover up their activities, said Sánchez-Garzoli. Social media videos have circulated of shooting from helicopters, tear gas thrown into a public transport bus, and plainclothes officers firing from a bus.

The political rhetoric has also been volatile. Defense Minister Diego Molano compared demonstrators to terrorists, while comments by former president Álvaro Uribe defending the use of firearms against demonstrators were later removed by Twitter for glorifying violence. The commander of Colombia’s army, meanwhile, recorded a video expressing “love” and “admiration” for the country’s ESMAD anti-riot police – who he does not command – calling them “heroes in black” and urging them to continue their current strategy.

“People felt for a long time that the government was not listening to them at their worst moment, right at the moment when shit was hitting the fan.”

Undeterred by the excessive violence and hostile words from public figures, thousands of demonstrators have continued to turn out across the country day after day, denouncing inequality, poverty, and government neglect.

“People felt for a long time that the government was not listening to them at their worst moment, right at the moment when shit was hitting the fan,” said Colombian political analyst Sergio Guzmán. “At the moment when unemployment was already at 14.2 percent, when inequality is on the rise, poverty rates went up 10 points here year on year, and they feel that the government's efforts to address this situation have fallen short.”

Prior to the protests, many officials warned citizens not to turn out, fearful of worsening the dire COVID-19 situation. Organisers have argued that few outbreaks have been linked to open-air protests. Many marchers said they feared the violence and neglect of their own government more than the coronavirus, and that the poverty, unemployment, and lack of opportunity that originally drove them to the streets have been compounded by the pandemic.

“COVID is the issue that's worsened all of the underlying problems,” said Guzmán. “None of this would have happened absent COVID.”

‘They have no future’

Colombia implemented strict quarantine measures from March until September 2020. Other partial quarantine measures have been implemented sporadically since as cases have peaked. December holiday celebrations caused a second peak in January, and it is now experiencing a third, with the highest infection and death rates seen so far. Currently, the 50 million population has seen nearly three million cases and over 77,000 deaths.

Colombia was the last of the Latin American countries to start the vaccine rollout, and although it has now administered over six million vaccines, it has been criticised for its slow rollout compared to its neighbours.

Olga Araújo Casanova, a Nomadesc board member, said long-standing health and education inequalities also drive the discontent, aggravated by quarantine restrictions that forced children to shift to virtual classes, many of them in areas without internet access. In Colombia, many children have been missing school for months. About 60 percent of children who have missed a year of school are in Latin America, according to UNICEF.

Araújo explained how Cali, specifically, was shifting from an “industrialised city to a tourist city”, and said the pandemic had dealt a big blow to the 70 percent of its population working informal jobs in food and nightlife sectors that have now disappeared.

More broadly, she said Colombia’s students and unemployed youth were turning out to protest in their masses because their futures will be those most impacted by the pandemic and they feel they have nothing to lose.

“That was the generation that grew up in total uncertainty. And it is the generation of the ‘non-future’ – they have no future. They don’t have education; they don’t have food; they don’t have housing; they don’t have jobs – they have nothing,” she said. “And those are the young people who are in the streets today because they say ‘the only thing we have is life, and we’re putting our life on the line’.”

gg/pdd/ag