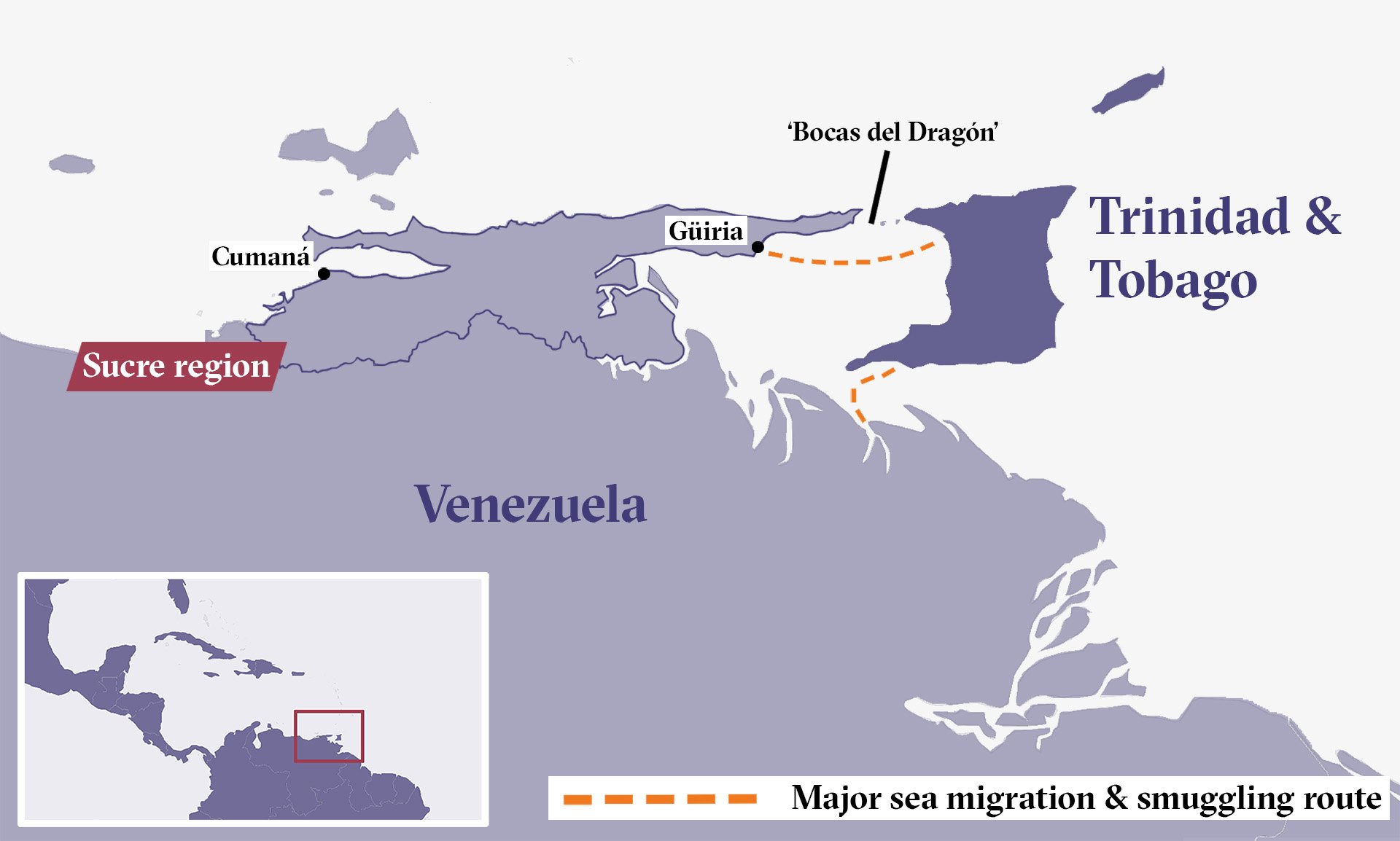

Far from the well-trodden border crossings in western Venezuela, shrinking resources and acute gas shortages have left many increasingly desperate residents along the Caribbean coast with few options other than a dangerous maritime crossing if they want to leave.

Only 24 kilometres away, Trinidad and Tobago has become an important destination country for some of the millions of Venezuelans who have been eager to escape the country’s economic meltdown and humanitarian crisis.

But in order to get there, they have to cross the Bocas del Dragón (Mouths of the Dragon) – a dangerous waterway known for human smuggling, narco-trafficking, shipwrecks, and even piracy – before hoping to slip past immigration officials upon landing in Trinidad.

Shipwrecks have proliferated in recent years. Three boats were reported missing in 2019, with a total of at least 80 people on board. Last December, another vessel sank in choppy waters, drowning at least 36 Venezuelans, including several children – the second such disaster of 2020. And just last week, a boat carrying 24 Venezuelans bound for Trinidad and Tobago capsized off the same coast, leaving at least 17 people dead or presumed dead.

“Most of them haven’t received health support, or have mild malnutrition, or have endured extreme poverty for years.”

As Venezuela reels from a second wave of COVID-19 infections that have resulted in intense lockdowns throughout the country, as well as confirmed cases of the more infectious “Brazilian” variant, more Venezuelans are expected to soon be braving the journey, especially as border restrictions reduce other migration pathways. On arrival though, many become victims of exploitation, while xenophobic rhetoric from public officials is also on the rise.

Beatriz Borges, director of the Venezuelan civil society group Cepaz, said the migrants are often drawn by the tourism industry in the Caribbean islands for work opportunities, but added that many of them have also been enduring extremely tough circumstances for a long time.

“Most of them haven’t received health support, or have mild malnutrition, or have endured extreme poverty for years,” Borges told The New Humanitarian.

A recent UN report suggests 2.5 million Venezuelans face severe food insecurity, and earlier reports estimate a third of the population needs food assistance. According to the UN, more than 5.5 million Venezuelans have left the country since the start of the country’s crisis.

‘Anything it takes’

“They all want to leave; they are all willing to do anything it takes to finally be able to live somewhere else,” said Alexandra, who lives with her children, partner, and parents in Güiria, the most populous town on the northeastern Paria peninsula and a key hub for Venezuelans seeking to migrate.

The 27-year-old, who previously worked as an undoumented migrant in Trinidad and Tobago, asked that her last name not be used as she plans to return and wanted to protect her security.

“I have two children, and life in Venezuela just kept getting more and more expensive,” Alexandra said, explaining how a friend had told her that if she went to Trinidad and Tobago for a few months, she would come back with enough money to support her family for a while.

When she and her partner travelled there in May 2017, she got a job through a broker that was supposed to pay $400 a month. “They didn’t pay what they promised, but we still made an effort to bring money back,” Alexandra recalled.

The couple was forced to return to Venezuela after just two months when their landlord evicted them for being three days late in paying their rent.

They wanted to return earlier and stay long enough to bring their children, but the pandemic put their plans on hold. They are still desperate to return.

“We are stuck in Venezuela without a job and trying to survive on the little money we had saved,” Alexandra said in a recent phone interview.

Venezuelans have faced a worsening economic crisis and humanitarian emergency since 2014, and the country’s northern coasts have been particularly hard hit due to lack of tourism; the expropriation of Cumaná – the Sucre region’s main port – by the national oil company; and the impact of organised crime on small-scale fishing.

The most recent study by Venezuela’s National Institute of Statistics (INE), released in 2016, reported that 52 percent of Sucre’s nearly one million residents lived in poverty, and 20 percent experienced extreme poverty. The unemployment rate stood at 42 percent. Those numbers are likely to have risen a lot since, as Venezuela’s overall situation has rapidly declined, with 5,500 percent inflation forecast for 2021.

Strained resources in Trinidad and Tobago

In recent years, as Venezuela’s humanitarian crisis has deepened, tens of thousands living along these coasts have made regular trips across the straits to Caribbean islands in search of food, medicine, and work.

Many have sought to settle in Trinidad and Tobago, and the country has become more protective of its borders with sometimes stark results.

According to official estimates, there are around 24,000 Venezuelan migrants in Trinidad and Tobago, which has a population of nearly 1.4 million people. That official number is likely low as most migrants enter the country by irregular means and never have interactions with government systems or officials. A 2019 report by Refugees International put the number of Venezuelans on the island at 40,000 and quickly growing – which would give the country the highest per capita Venezuelan population in the Carribean.

A 2019 *internal review by the country's one and only immigration detention centre (IDC) – made public in March 2020 by a parliamentary inqury – disagreements between government bodies over the official estimate, but made one issue clear: The small island nation finds its resources increasingly strained by the Venezuelan influx.

Included in the document are the minutes of a meeting between IDC officials, NGOs, and a government representative in which the IDC complains about not having the budget to continue housing detained migrants in satisfactory conditions.

Sex trafficking

Borges said the irregular nature of most migrant journeys – which entail hiring smugglers, getting jobs through brokers, and working undocumented – also “puts them at greater risk of being victims of sexual and labour exploitation”.

Cleophas Justine Pierre, an expert on Caribbean migration, estimated in a 2019 study that nearly 4,000 victims from Güiria alone had been trafficked to Trinidad and Tobago over the previous six years. Again, such figures are likely to have grown since.

Sara Gómez, an undocumented migrant who arrived by boat in 2020, said that vulnerable migrants without other options often turn to survival sex work.

“You see a lot of girls that end up working as prostitutes,” she said. “And I don’t judge them. When your options are to work for slave wages cleaning toilets or feed your family by [sex work], I know which I would choose.”

Gómez herself works informally as a janitor at a fast food restaurant. “I used to be a teacher in Venezuela,” she said. “I don’t like my job here, and it pays worse than minimum wage. But at least they don’t beat me.”

She said she worried about deportation, and noted there was little recourse for abused migrants. Gómez described being robbed as well as physically assaulted by her former employer: “I lost all forms of identification. But I can’t go to the police to report [either] crime because they will just deport me.”

“Opportunities here for migrants, especially women, are very limited,” Gómez added.

Julio Henríquez, director of the Refugee Freedom Project and an immigration lawyer who provides free services to Venezuelans in Trinidad, described a black market scene of exploitation, insecurity, and sex trafficking.

“I used to be a teacher in Venezuela. I don’t like my job here, and it pays worse than minimum wage. But at least they don’t beat me.”

“We have seen an explosion among sexual trafficking among our clients, sexual violence upon women scared of going to the police, even cases of women who are effectively sold to pay off their debt to the smugglers who brought them to the island,” he said.

Trinidadian media has reported cases of immigration and law enforcement officials working directly with criminals involved in the sexual trafficking of migrants, as well of women sold into sexual slavery.

A 2020 human trafficking report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) – which was more thorough in reviewing other regions of the Caribbean – contained only limited information on the situation in Trinidad and Tobago. It said that in 2017 and 2018, the government reported 16 victims of human trafficking, 13 of whom were Venezuelan women. There was no further information nor did the government provide data for more recent years.

Henríquez, who represents registered asylum seekers, believes the real number of trafficked Venezuelans is far higher. “It’s something that government officials won’t acknowledge is happening,” he said. “They have created a system that incentivises ignoring these issues. The very same governmental bodies that are supposed to protect them have failed.”

Asylum difficulties

To be granted asylum, migrants must prove they will face credible risk in their home country. The government of Trinidad and Tobago considers all other Venezuelans “economic migrants”, who are not protected under Trinidadian law.

In theory, new arrivals have the right to claim asylum, but in practice there is no governmental body to enforce these rights. Describing a system in which compliance is merely voluntary for immigration officials, Henríquez said it is seen as much easier to simply deport refugees rather than be responsible for their long-term care.

For migrants unable to return to Venezuela, Trinidad and Tobago has no formal system to apply for asylum. They can only apply through the Living Water Community, a local NGO that works with the government and UN offices to expedite claims. The migrants are usually detained by the IDC while their cases proceed.

In **2014, the Trinidadian government signed a non-binding agreement based on the Cartagena Declaration on Refugees, but has rejected both enshrining the agreement into law and the oversight of regional organisations such as the Organization of American States (OAS), which it accuses of “promoting disinformation'' and “politicising the crisis”. It has also ignored suggestions to formalise migrant rights from NGOs and non-profits that operate in the region, such as the Living Water Community.

Rochelle Nakhid, coordinator of the Living Water Community's Ministry for Migrants and Refugees, described establishing the first office in Trinidad and Tobago alongside the UN in 2009, when the government offered no legal protections for asylum seekers at all.

“There was no history of receiving immigrants,” she said by telephone. “There was no UNHCR presence; just liaisons," she added, explaining that national Red Cross organisations were supporting the UN's refugee agency throughout the Caribbean until five or six years ago as it had no presence in the region.

In 2015, when the Venezuelan exodus began in earnest, Trinidad and Tobago soon became completely overwhelmed. Since then, the island nation has experienced an influx of both formal and informal immigration from their southern neighbours.

Despite this surge, according to the internal IDC review, Trinidad had only one employee in 2019 who spoke Spanish in the entire IDC organisation, and only at “intermediate” level. At the time, according to the review, over 80 percent of detained migrants in the IDC system were from Venezuela, a Spanish-speaking country.

Increasing xenophobia

In 2018, the Trinidadian government changed its response to the immigration crisis. Though immigrants were formerly granted free movement as their cases went through court, the policy became one of detention for asylum seekers. “We started to see some mass detention events after the change,” said Nakhid. “This trend accelerated in 2020, during elections.”

During that year, there were multiple mass detentions of migrants as well as mass deportations of new arrivals.

In July 2020, Trinidad and Tobago’s security minister called Venezuelans “boat people” who “represented a serious health issue”, and gave the number of a hotline for residents to report those without documentation. Police Commissioner Gary Griffith recently suggested the policy doesn’t go far enough, saying the current rules promote the spread of COVID-19 and amount to a “get out jail free card”.

“The government wants to blame their failings on outsiders, and the COVID crisis has made this worse.”

Manuel Romero, a Venezulean immigrant granted refugee status in Trinidad and Tobago, now acts as a liaison for Living Water. The former judge fled Venezuela after the intelligence services made death threats against him and his family over rulings they disapproved of.

“Xenophobia wasn't common among the people here when I arrived in 2018,” Romero said. “Trinidadian people are very kind and welcoming. But I have seen the rhetoric from public officials grow darker ever since. The government wants to blame their failings on outsiders, and the COVID crisis has made this worse.”

At a recent press conference, Prime Minister Keith Rowley denied the claims of xenophobia in a response to The New Humanitarian, and pointed to government plans to provide free vaccination to the migrants as evidence.

“Bigotry and xenophobia do not help us as a nation, and they certainly do not help us overcome this historical health crisis,” he said.

Meanwhile, as humanitarian needs within Venezuela are expected to grow this year, there is no sign that migratory flows to the island are abating.

For Alexandra, struggling to earn a living for herself and her family by selling street food in Güiria, there is little that would keep her from trying to return to Trinidad and Tobago.

“Life in Venezuela is hard, sometimes impossible,” she said. “We usually don’t find any options to survive. Food is scarce and very expensive. We just want to work.”

Additional reporting by Gabriela Mesones Rojo in Madrid.

(*An earlier version of this story stated that the internal IDC review had been obtained by The New Humanitarian. This story was updated on 30 April 2021 to clarify that the internal review had been made public by a parliamentary inquiry in March 2020. **The earlier version also incorrectly gave the year of the signing of the non-binding agreement as 2020 instead of 2014.)

jc-gm-cr/as/ag