Zulma Mosquera didn’t want to leave Buenaventura, the Pacific port city of more than 450,000 people in western Colombia where she grew up, and where she and her four children called home. But, like hundreds like her in recent weeks, she felt she had to escape.

The exodus has been propelled by a wave of gang violence that started in late December, but residents say it’s also the result of racialised neglect in a city where the population – which is 85 percent Afro-Colombian – struggles even for basic public services.

Driven by concern over worsening crime but also by anger over longstanding marginalisation, hundreds took to the streets of Buenaventura last month in a series of demonstrations, blocking access to the port and calling for urgent government intervention.

“The government and businessmen need to understand that we’re not animals that live here, that we’re people who live here who need to be treated with dignity,” Danelly Estupiñán, an activist who works with a local NGO called the Process of Black Communities, or PCN, told The New Humanitarian.

The Buenaventura protests feed into a growing nationwide movement by Indigenous groups and Afro-Colombians, demanding action from President Iván Duque to combat deepening poverty and rising lawlessness in western and southwestern regions despite Colombia’s landmark 2016 peace accords.

The UN’s human rights body called last month on Duque to fully implement the peace deal, urging the Colombian government to do more to protect rights activists and civilians, and to increase its presence in the poorer, more remote parts of the country.

The port of Buenaventura, which handles more than half of Colombia’s imports and exports, is a centre for cocaine trafficking. Gangs wage sporadic turf wars within the city, while guerrilla and paramilitary groups also vie for control of the routes into town from the wider region.

At the beginning of this year, the city experienced a surge of violence as La Local, the main organised crime group, reportedly split into two rival factions. In the first 33 days, there were 33 firefights in various city neighbourhoods, displacing 1,700 families and 6,000 people, according to the Inter-Church Justice and Peace Commission. There were three times as many homicides this January compared to the same month last year, according to the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) think tank.

For Mosquera, 38, the troubles began to hit too close to home. First, a gang of armed men tried to recruit her 16-year old son, whose name she declined to reveal. Then, they threatened Mosquera herself for her work on a violence-prevention campaign. “Literally, I was paralysed [by fear],” she said. “This is when they kill me,” she recalled thinking.

On the night of 17 January, Mosquera and her four children drove to the neighbouring city of Cali to seek refuge. She told TNH by phone that they were struggling in Cali as they couldn’t access government benefits for victims displaced by conflict. Still, she felt they were better off than in Buenaventura, where the gangs recruit children forcibly, extort money from businesses, and threaten or kill those who don’t observe their curfews or “turf borders”.

Crime fills the void

As well as aiming to end the conflict, Colombia’s 2016 accords were supposed to increase security and provide economic opportunities for Afro-Colombian and Indigenous communities in the rural coca-producing areas that had been controlled by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) guerrillas.

Instead, when the FARC disarmed, this led to a vacuum exploited by criminal and paramilitary groups. Battles for control of trafficking routes and territory have sent victims fleeing from the countryside to cities like Buenaventura, making their problems worse.

Armed groups and gangs control almost everything in Buenaventura nowadays, demanding illegal taxes from everyone – down to the smallest street vendor – driving up the price of even the most basic groceries.

Few residents can afford the higher prices, and that has caused local businesses to close, increasing sky-high unemployment. The city’s largest employer is the port, where residents say locals get the lowest-paying jobs with no benefits, are fired if they get injured, and receive death threats if they try to unionise.

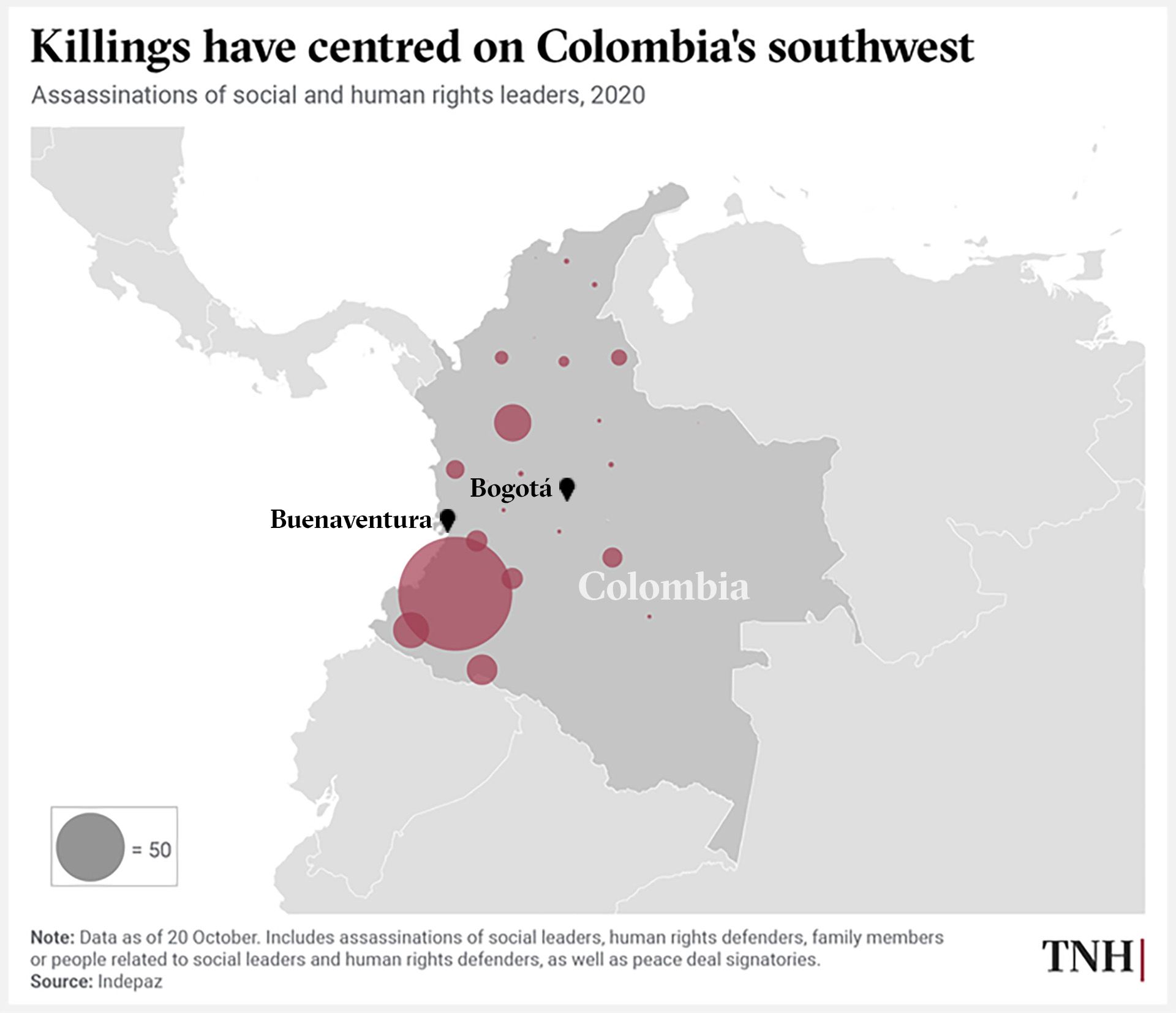

The threats are real. More than 1,000 social leaders and activists have been killed in Colombia since the 2016 peace deal (in 2013, the annual number was only 10), according to Indepaz, a Colombian NGO that keeps a tally of the deaths. Most of those killed have been Indigenous or Afro-Colombian people in western and southwestern regions.

Estupiñán has faced death threats over the past few years because of her investigations into human rights abuses in the city. Twice, she has had to leave, and she still can’t move around freely without an armoured car and two bodyguards.

For Estupiñán, though, the dire situation in Buenaventura isn’t only down to the drugs and the crime: It’s a consequence of the deeper marginalisation of Afro-Colombians by the state over several decades.

“Obviously, it is not a matter of just location. It is a matter of who is inside the strategic territory,” she said, referring to the city that surrounds the port. “Who inhabits it? It is inhabited by Blacks. Who are the Blacks? People of lesser worth.”

Estupiñán said this racism manifests itself in how the government invests in Buenaventura’s port but not in its society. It has improved the roads that lead to the port, but not those over which residents inland must travel for hours to reach medical care. Estupiñán said she sees it too in the rainwater used for drinking, bathing, and cooking; in the children who don’t know what it is to take a shower; and in the young people who are forcibly recruited and turned into what she called “war machines”.

Not the first protests

The city’s lack of basic services – such as potable water, reliable electricity, adequate housing, healthcare, and schools – has provoked protests in the past, and crackdowns by Colombia’s anti-riot police.

In 2017, a so-called “Civic Strike” blocked access to the port for 22 days. The state responded with violence, tear gas, and detention. Eventually, after the protests continued regardless, the government agreed to create a fund to address the problems. This did mark a turning point of sorts – resulting in the re-opening of the hospital and a new intensive care unit – but residents said most promises haven’t been kept.

In the years prior to the 2016 peace agreement, the city was known for its “chop houses”, where gangs tortured and murdered victims before leaving their remains in public to generate fear. The brutality drew so much attention that the government heavily militarised the region.

But there’s little trust here in the police or the army.

Residents say it’s widely known that the armed groups – several of which splintered off from paramilitary organisations like the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia – operate by colluding with, bribing, or terrorising local security forces, which are often outnumbered.

“We have a place where you literally have a member of the military armed with a rifle and everything on every block. And right in front of them, people are getting killed,” Gimena Sánchez-Garzoli, WOLA’s Andes director, told TNH.

After the militarisation, homicides decreased, but disappearances rose. Until the recent string of unusual street firefights, gang violence, according to residents, had simply become less immediately visible.

While the coronavirus pandemic has prevented a full mobilisation on a par with 2017, demonstrators have been forming human chains to block access to the port and to draw attention to the security and humanitarian crisis.

Last month, an international delegation that included delegates from the German and French embassies – as well as from the UN, Oxfam, and Peace Brigades International – visited Buenaventura to document the situation on the ground.

Carlos Mejía, executive director of Oxfam Colombia, which has longstanding relationships with Buenaventura women’s groups, said international actors needed to use their diplomatic relationships to “make visible what is happening”.

They should “ask difficult questions about what the government is doing to offer a comprehensive solution for the development of the port and the city”, Mejía said.

Francia Márquez Mina, a leading human rights and environmental activist who spoke with TNH from an undisclosed location for security reasons, said the international community, which depends on the Buenaventura port for trade, has a responsibility to the territory.

“I believe that it is important that those countries that have a link with the port of Buenaventura, that profit from what happens in the port of Buenaventura, I believe that they have to assume their responsibility to stop this death that is occurring,” Márquez said.

Buenaventura’s mayor, Victor Hugo Vidal – elected in 2019 after rising to prominence as a leader of the 2017 Civic Strike in what was seen as a victory for the left and for activists – insists that progress against crime and social injustice is being made. “It is a task that is not so easy, but we are doing it,” he told an international delegation last month. Colombian Interior Minister Daniel Palacios has, meanwhile, announced plans to boost support to security forces and increase arrests of gang leaders.

The interior ministry, the defence ministry, and Duque’s office all failed to respond to requests for comment on the situation in Buenaventura in time for publication.

Patterns of poverty and race

David Murillo, who studies ethno-racial justice at the non-profit human rights organisation Dejusticia, called the situation in Buenaventura the “tip of the iceberg” in terms of the Colombian state’s abandonment of its citizens, its lack of concern for violence against activists, and what he said was the normalisation of institutional racism.

“Throughout the Afro population in Colombia, the social and economic conditions are very similar,” Murillo said, adding that it was telling that demonstrators in the Pacific Afro-majority department of Chocó made essentially the same demands several years ago as those now being made in Buenaventura.

While Afro-Colombians have long been relegated to living in the most neglected provinces and suffered from discrimination, structural racism is not acknowledged or discussed among the general public, and is rarely mentioned in Colombia’s mainstream media.

Rates of infant mortality, hunger, illiteracy, and forced displacement for Afro-descendants are far higher than those of the majority white-mestizo population, and access to services like sewage and potable water is about half that of the overall population.

Many of the jobs with the worst labour rights violations are held primarily by Afro-Colombians, said WOLA’s Sánchez-Garzoli, adding that when she lobbies for political protection for human rights defenders, the authorities are more suspicious of the claims of Afro-Colombian leaders.

“Here, there has been an underhanded racism,” said Luz Marina Becerra, a board member of the National Association of Displaced Afro-Colombians. “Racism that people do not want to recognise, but deep down they know it does exist.”

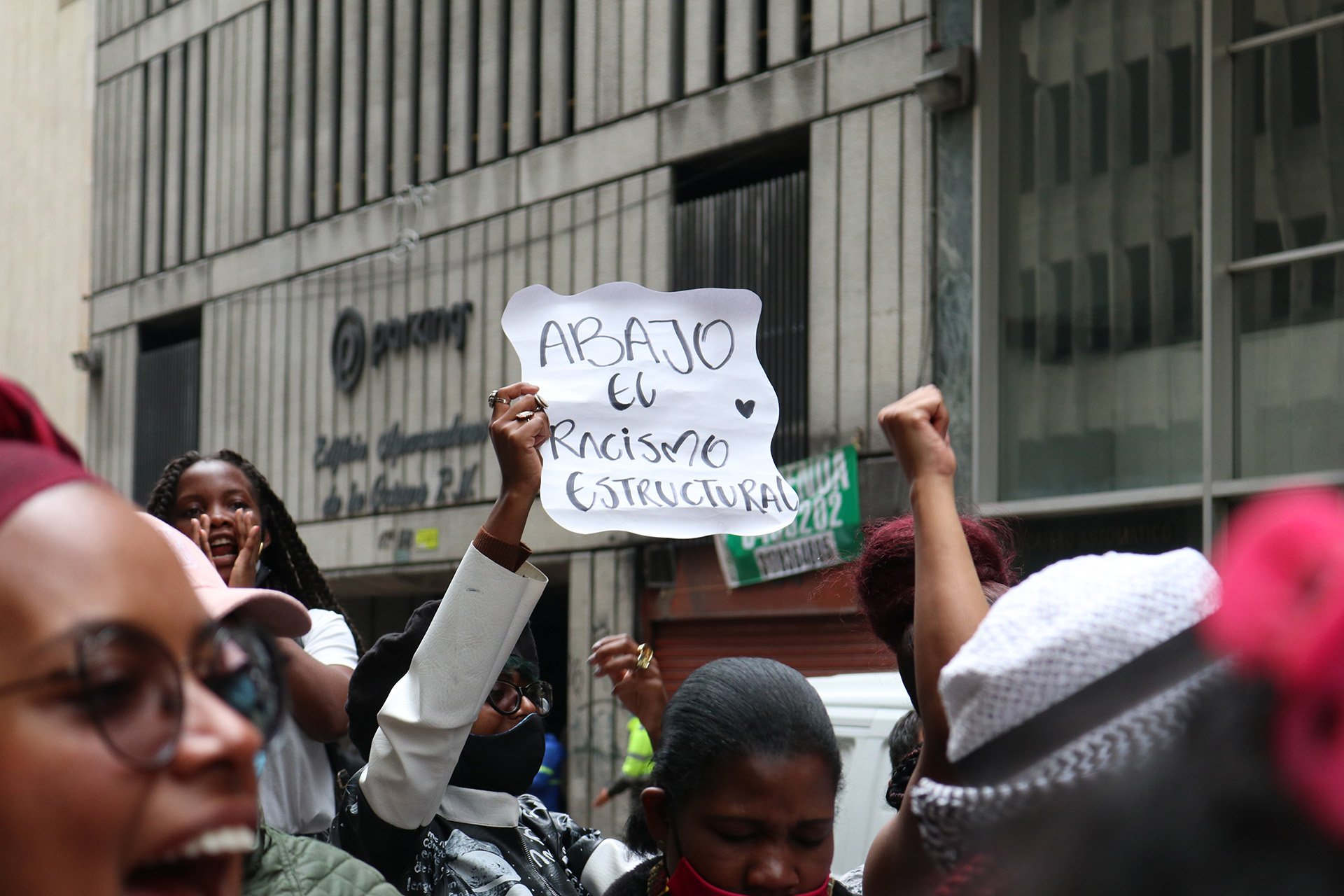

She spoke to TNH on 12 February amidst chants of “racismo, racismo, racismo estructural” (“racism, racism, structural racism”) as participants from various Afro-Colombian organisations rallied outside the interior ministry in the capital, Bogotá, to demand action – not only for Buenaventura, but for other regions with high Afro-Colombian populations, such as Tumaco, Nariño, and Chocó.

“Racism in the United States was open. It was open, and that allowed communities to organise and have the power they have today,” Becerra said. “People here don't recognise it, but clearly it is structural racism. But it is also everyday racism.”

TNH used transportation provided by the NGO Nomadesc.

gg/pdd/dm/ag