Even as the fourth anniversary of a landmark peace accord came and went in late November, conflict and extortion were driving rising numbers of people from their homes in Colombia’s most lawless regions.

“There have been three major displacements in regions outside of the city since September,” journalist Éder Narváez Sierra told The New Humanitarian, flanked by two large state-provided bodyguards as he drank a coffee in a small bakery in Caucasia.

The city is part of a conflict zone in Colombia’s northern Bajo Cauca region, where illegal mining, coca production, and extortion are the economic lifeblood of the rival armed groups whose violence and threats are behind the string of displacements.

In September, 206 families were forced to flee to Caucasia from Cáceres, 38 kilometres away, following threats from Los Caparros, a criminal paramilitary “self-defense force” currently in conflict with two other armed groups in the region.

On 18 November, another 70 people fled the same town when Los Caparros imposed an armed curfew in response to the death of one of its leaders at the hands of the Colombian military. Many of those affected came from Indigenous communities.

According to an August congressional report on the implementation of the 2016 peace accord, 16,190 people were displaced by violence in Colombia in the first six months of 2020 – almost double the number in the same period in 2019. The country holds the dubious distinction of having the second largest population of internally displaced people in the world, behind only Syria.

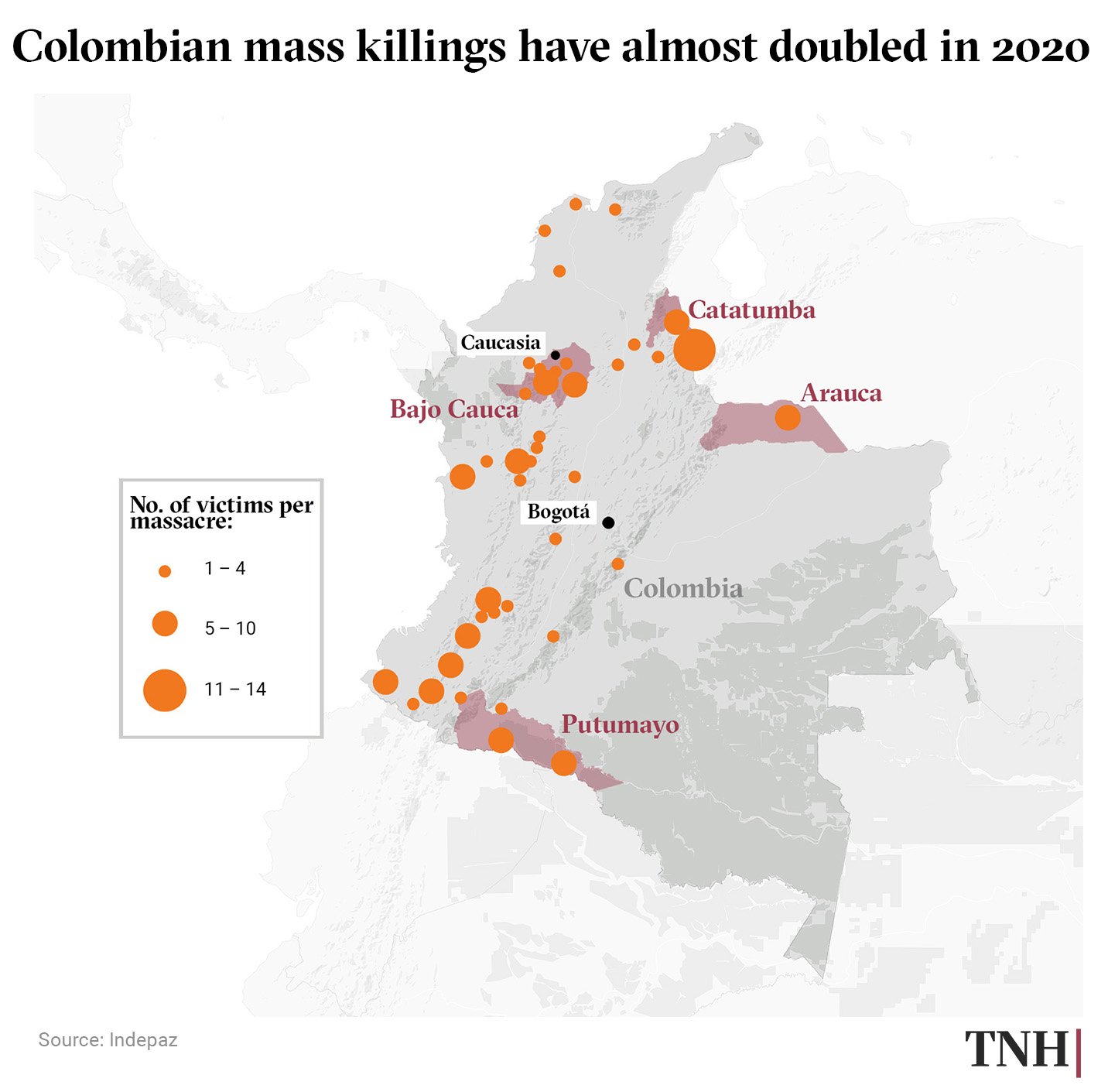

The sub-region of Bajo Cauca, in Antioquia, is one of four areas in Colombia where displacement rates have been highest. Unlike the more remote troubled regions of Arauca, Catatumbo, and Putumayo, the conflict zone around Caucasia is just a few hours drive from the major city of Medellín, along accessible highways.

Narváez Sierra isn’t sure how many death threats he has received while working for NP Noticias Online, a web-based media company in the region. In the seven years he has been covering criminal activity in Caucasia, two of his colleagues have been killed. He explained that the region has long been unstable due to territorial disputes between armed groups over mineral riches, fertile land for coca cultivation, and control of major drug-trafficking routes to the Pacific and Atlantic coasts.

“More than 50 percent of businesses in Caucasia have to pay the vacuna,” said Narváez Sierra, using the common slang term (the “vaccine”) for the monthly extortion payments paid by civilians to avoid problems with criminal groups.

Members of the leftist ELN guerrilla group, ex-FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) fighters, as well as spin-offs of right-wing paramilitary outfits such as the Clan del Golfo and Los Caparros, all compete for mining resources, coca fields, and extortion territory in Bajo Cauca.

During most of the 50-year Colombian civil war, the region was controlled largely by the FARC, which often battled the state for the valuable gold resources.

In the mid-1980s, the region became contested as right-wing paramilitary “self-defense” groups, or paracos, began to fight guerrilla groups alongside the government. The paracos were engaged in the same illegal activities as the guerrillas and committed atrocities of their own.

The Clan del Golfo, also known as the Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia, and Los Caparros are splinter groups from those same right-wing paramilitary forces.

The COVID-19 pandemic only appears to have made the competition for resources more intense. After the lockdown was imposed, extortion incomes dropped as many businesses failed, and armed groups had to focus on other revenue streams to finance their activities.

“Many small business owners are leaving the city because they can’t succeed here,” Narváez Sierra said. “In September, a barber was killed by armed assailants as he opened his shop at nine in the morning. He hadn’t paid the vacuna in two months, so they made an example of him.”

The recent COVID-19 restrictions have also forced criminal groups to adapt. Some have even imposed their own lockdown measures and used the crisis to increase both territorial control and recruitment, including the forced recruitment of minors.

Coca, gold, and ‘taxes’

Reasons for rising displacement vary from region to region, but critics of President Iván Duque’s right-wing administration say local problems are made worse by a central government that prefers military to civilian solutions.

“The [national] government says ‘illegal mining is controlled by armed groups’,” explained Nadir de Hoyos, who works in the mayor's office in Cáceres. “And that’s true, strictly-speaking.

“But you have to look a little deeper to understand what is really going on. People here work almost completely informally. There is very little state presence. So when an armed group takes over the territory, they say to people who have always been miners, ‘Now, 30 percent of your earnings are ours, and we will regulate the industry’. These people are just workers, in civil society. They aren’t members of ELN, or Los Caparros – they are just forced to pay them taxes.”

According to de Hoyos, when the Colombian armed forces arrive, they destroy the mines and criminalise those who are working them illegally.

“Much like how the government approaches coca cultivation, they aren’t offering an alternative,” he said. “A military solution alone won’t solve the problem, and in some ways it makes the instability worse, leaving behind a population without work who doesn’t trust government intentions.”

De Hoyos described growing frustration between municipal governments trying to deal with the broader social issues, and the Colombian military forces – controlled by the federal government – who look only at punitive and strategic objectives rather than an integrated response to the conflict.

Illegal mining has long been a source of both environmental and social problems in Colombia. The areas near Caucasia are rich in mineral deposits of both gold and silver, and despite government enforcement of regulations and the destruction of illegal mines, this income source has become even more important to armed groups as lockdown measures have made narco-trafficking more difficult and extortion less profitable.

“Minerals are relatively easy to sell,” said Mathew Charles, a research fellow at the Colombian Observatory of Organized Crime, or OCCO. “There is a quick turnaround, as opposed to say, cocaine, which has to be shipped north before payment arrives.

“Though government efforts to regulate mining in Bajo Cauca have decreased the total number of mines, armed groups feeling the pinch of contraction or engaged in a war with other groups – such as Los Caparros and the Clan del Golfo currently are in the region – may be focusing their efforts on mining to obtain a quick infusion of resources.”

When these groups fight, civilians are often caught in the crossfire.

“Contested areas are more dangerous for civilians than territories securely held by armed groups,” explained Shauna Gillooly, a peacebuilding and conflict researcher for University of California, Irvine, who is based in Colombia. “When armed groups are fighting to control a region, no one knows what rules they are supposed to follow, and the groups often commit atrocities to inspire fear of working with the other side.”

In Bajo Cauca, these territorial disputes – over mining, coca fields, and extortion areas – are leading to more massacres as well as more displacements. Across Colombia, 349 people have been killed in 79 mass killings (more than three people) this year, as of 10 December – nearly double the amount of victims in 2019.

Growing slums

Caucasia is home to the biggest “invasiones” – a term the government uses to describe neighbourhoods of squatters who have built improvised housing on land they don’t own – in all of Colombia.

Narváez Sierra explained how some of those displaced by the violence end up in the invasiones with no job opportunities and suffering from hunger – fertile recruiting ground for cartels and criminal gangs.

The slums are a labyrinthine network of shelters built from bricks, found wood, cardboard and scrap metal that stretch out from the northern limits of the city. These areas of extreme urban poverty, which now boast a population of tens of thousands, have grown steadily as violence in rural areas of Bajo Cauca has increased over the past decade.

“My wife and I came here after the death threats in Cáceres,” Iván, who asked that his real name be withheld for fear of retaliation, told TNH. “We have no option but to stay with family here [in the invasiones].”

Iván ekes out a living selling fish he catches in the nearby river to merchants in Caucasia. “I’m looking for more steady work, and the government helps us a bit with food,” he said. “I have faith in God that we will find a way to come out ahead.”

Displacement from violence in the region peaked in the mid-2000s – more than 5,000 people fled from rural areas in 2008 alone, at the height of the civil war – before tapering off. But they are on the rise again.

“Armed groups have changed their tactics compared to recent years,” said Narváez Sierra. “We see more massacres. We see more child recruitment. We have experienced a number of child sicarios (assassins) this year. The groups flee to where the army is not present rather than trying to hold territory by force, and commit gruesome displays of violence to intimidate rivals. This puts civilians even more at risk.”

A January Colombian Chamber of Commerce report stated that over half of the residents in Bajo Cauca live in poverty, with 42 percent identifying as “destitute”, which the study defined as not having enough resources for basic food or stable housing.

Field missions to Bajo Cuaca by Fundación Paz y Reconciliación, or PARES, a Colombian NGO that is monitoring the implementation of the peace process, suggests that rates of poverty, inequality, and malnutrition have all risen considerably since the arrival of COVID-19.

In the city of Caucasia at least, that growing humanitarian suffering is concentrated in the invasiones, the slums to the north.

Visiting the settlements, TNH witnessed the funeral procession of a 17-year-old girl who had been murdered, part of a rising tide of femicides nationally. In 2020, Caucasia experienced a 200 percent increase in homicides between January and November compared to the same period last year. Surrounding rural regions of Bajo Cauca fared similarly.

“The violence and insecurity cuts across all levels of society,” said Narváez Sierra. “And there is a critical mistrust between the community and the state. They see the government as either unable or unwilling to address these problems.”

Limited help, no solutions

La Unidad para las Víctimas, the government department tasked with housing displaced people in the region, released a statement on 25 November saying that half of those displaced in the last two months have since returned home, and the rest had chosen to “stay with family members in Caucasia”.

The office – which provides food and basic hygiene items to the displaced in Caucasia, while offering temporary shelter housing to those interested – denied requests for additional information and comment. “Security is of paramount concern,” an employee, who gave no name, told TNH in a phone call. “The population is extremely vulnerable and under direct threat of life from criminal groups. We are unable to give further information on details of displaced persons or specific actions of this office.”

The Antioquia office of the International Committee of the Red Cross, which has no permanent presence in Caucasia, said that the ICRC conducts field missions in the region to provide both food and health assistance. “Systemic violence and displacement, as well as food insecurity are chronic issues in Bajo Cauca,” the spokesperson, Lorena Hoyos, told TNH by phone. “We are unable to comment in detail on our activities in the region due to our positions of neutrality and confidentiality.”

Colombian media has reported at least one instance of the ICRC acting as intermediaries during negotiations with armed groups in Bajo Cauca to release kidnapping victims.

Asked for solutions, Narváez Sierra looked pensively into his coffee before replying.

“Civilians are the ones paying the cost, both from violence by armed actors and violence by the state,” he said. “The military component of the government strategy is necessary, sadly. We have reached a point where that is undeniable. But the social and economic components are missing.”

All the experts TNH spoke to expected displacements around Caucasia to continue.

“A decay of security in rural regions and growth of armed groups has been undeterred by the local authorities, and now these organised criminal groups are reaching dangerous levels of control,” said Sergio Guzman, director of Colombia Risk Analysis, a research and consultancy group in the Colombian capital, Bogotá. “They are principal players economically speaking and are playing a growing political role as well.”

Narváez Sierra agreed. “If [the government doesn’t] provide an integrated response that includes education for all classes of people, investment in infrastructure, and an alternative to the black market economy, we will be at war forever,” he said.

jc/pdd/ag