As Honduras endures its second major hurricane in as many weeks, international aid agencies and local volunteer groups are scrambling the best responses they can to assist people displaced by flooding and landslides.

But aid experts and rights activists, as well as local residents and politicians, say longer-term problems are being neglected in a country where years of devastating drought have caused mass hunger and are leading thousands of Hondurans to flee annually towards the United States.

Read more → ‘The Ixil helping the Ixil’: Indigenous people in Guatemala lead their own Hurricane Eta response

Yamely Cáceres was displaced from her Chamalecón neighbourhood in San Pedro Sula in northern Honduras after flooding from Hurricane Eta, and then prevented from returning due to resurgent floods from Hurricane Iota, which crashed through the region from 16-18 November.

“People are losing everything,” Cáceres, who is now living under a highway overpass, told The New Humanitarian via WhatsApp. “They’re already losing so much with the El Niño droughts before this. I bet more and more people are going to leave after this.”

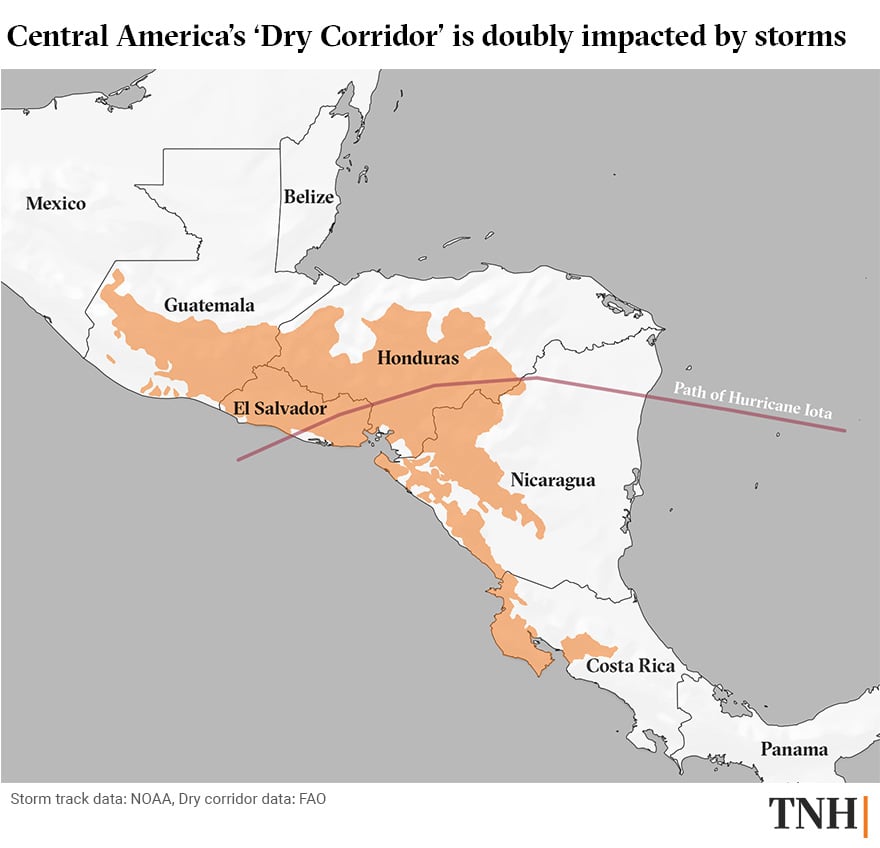

Though it’s hard to pin down the exact extent to which climate change is responsible for this unprecedented season of storms, there’s far less doubt about its key role – over several decades – in causing perennial drought in what is known as the “Dry Corridor”.

Scientists say the droughts are driven by El Niño, a periodic but extreme iteration of global weather shifts made more intense by climate change. Since the Dry Corridor catchphrase began being used in 2009, the area – a stretch of often parched mountainous farmland running from Guatemala to northern Costa Rica – has become home to systematic hunger and malnutrition. Some 3.5 million people – or one in six people in the three worst-affected countries – are estimated to have faced food insecurity in the past 10 years due to the drought cycle.

The US National Weather Service describes ENSO – the El Niño Southern Oscillation – as “one of the most important climate phenomena on Earth due to its ability to change the global atmospheric circulation, which in turn, influences temperature and precipitation across the globe.” When it occurs, Central America’s Pacific coast receives little to none of the summer rains necessary for crop growth.

The arrival of Hurricanes Eta and Iota in early November, which have so far affected approximately three million people in Honduras alone, marked the reversal of the phenomenon, due to La Niña, which sees surface temperatures in the east-central Pacific drift below average to generate volatile hurricane seasons.

Though droughts – and hunger – are by no means new to the region, they’ve been worsening in recent decades. According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the first major warning signs emerged in 2001 when abnormal rainfall patterns severely reduced or destroyed the crop harvests for corn, sorghum, and rice.

In 2014 and 2015, successive El Niño-induced droughts created compounding effects of such scale that the issue of hunger driving migration briefly leapt to the forefront of the international agenda.

But as droughts have worsened, so have storms and extreme flooding, so that when long-awaited rains do in the end appear, catastrophic downpours provoke deadly landslides and wash away much of the already parched surface soils.

Fuelling the migration is systematic violence. Many of those fleeing rural hunger move into city slums with few jobs and poor to non-existent infrastructure, where gang violence prevails. This in turn drives many to join migrant caravans, that include people from other Dry Corridor countries – notably Guatemala and El Salvador, which together with Honduras make up the violence-plagued Northern Triangle – fleeing north to the United States.

Conor Walsh, country representative for Catholic Relief Services, an international NGO that provides food aid in the Dry Corridor, explained how Hondurans are on the front line in terms of experiencing the humanitarian impacts of climate change today.

“It’s causing massive increases in storms while having repeated droughts,” Walsh told TNH. “We had three seasons of repeated droughts that were destroying crops, devastating food security, and driving people into the migration caravans. Drought isn’t just a one-time thing. It’s repeated droughts that drive them off of their land.”

Ruinous for farmers, food security

With 30 percent of Hondurans engaged in agriculture, including 70 percent in subsistence farming, prolonged droughts bookended by huge storms and floods have reduced crop yields by catastrophic amounts.

Feed the Future, a programme fighting food insecurity and funded by USAID – the US government’s foreign aid department – estimates that 45 percent of people now live below the poverty line in the six departments of western Honduras in the Dry Corridor.

In 2019, after four years of El Niño-driven droughts, the agricultural monitoring organisation GEOGLAM reported that small-scale subsistence farmers in the wider Dry Corridor region had experienced crop losses of 50 to 75 percent.

A 9 November report from the UN’s emergency aid coordination body, OCHA, said more than 150,000 hectares of crops in Honduras had been lost or damaged due to Hurricane Eta – a devastation of rural livelihoods expected to worsen with more flooding after Iota.

In a 13 November news release, the UN’s World Food Programme predicted that the food emergency in Honduras would deepen. It said the combined effects of catastrophic flooding and pre-existing economic precarity worsened by COVID-19 lockdowns meant the number of food insecure Hondurans would jump from 1.6 million in 2019 to three million by the end of 2020.

Edy Banegas, a forestry expert and human rights advocate working with the San Alonso Foundation, a Honduran human rights group supporting farmers, has observed the longer-term deterioration of food yields. “The harvests have fallen an extreme amount in recent years,” he told TNH. “People are having far less access to food, and therefore can’t even eat in many cases.”

Beyond climate change

Other factors have also been contributing to the crisis in rural Honduras.

“Year by year, through the processes of industrialisation, especially in the southern part of the country where deforestation is worse, the droughts have gotten worse and worse,” Eder Benítez, who works for the Center for Human Development, a human rights organisation in the southern city of Choluteca, told TNH.

For Bertita Zúñiga Cáceres, daughter of the murdered environmental activist Berta Cáceres, mining and monoculture agriculture – including palm oil plantations – are a large part of the problem as they damage the natural water systems.

Zúñiga Cáceres, a deputy in the Honduran Congress for the Intibucá department, said more attention should be focused on the watersheds created by these industries, which have proliferated since a military coup in 2009. According to her, corrupt political and economic practices have played a more immediate role than climate change in the worsening Dry Corridor droughts.

“In the last year, what we’ve experienced is the effects of deforestation and the invasion of territories,” she said. “It has to do a lot with the way the land is treated, so it seems weird to not be talking about that. There are so many extractive projects such as mining that suck up water and have a terrible environmental impact.”

Mario Argeñal, a resident of Danlí in the heart of the Dry Corridor, told TNH he has seen first-hand how deforestation has impacted water supplies. “The mountains here are already destroyed, because they sent off the pines and the forests to foreign buyers,” he said. “Now they don’t have the vegetation to filter and hold water. It’s the same with mining. It leaves us in a terrible crisis when things like this happen.”

For Banegas, the forestry expert, the only way to overcome hunger over the long-term in Honduras – and in the Dry Corridor – is to change the whole way of thinking about farming, and to move away from the idea of large-scale “profit-making agriculture”.

“What should we be doing? We should be changing the logic,” he said. “If we want to leave this situation… the first focus [should be] finding a sustainable model of agriculture for small-scale producers.”

Short-term assistance?

Elio Rujano, a representative for WFP’s regional bureau in Panama, told TNH via email that the agency “is supporting smallholder farmers... to become resilient to recurrent climate shocks while improving and protecting their food security and nutrition.”

WFP provides cash transfers for families unable to cultivate their own crops so they can buy groceries in times of emergency, as well as meals for children in rural schools.

For some Hondurans that TNH spoke to, the work of international aid groups provides a necessary remedy to a deepening crisis of hunger and poverty. But others felt it fails to attack the roots of the problem.

“It is really important that they don’t only bring food,” Benítez from the Center for Human Development said, regarding the aid sector in general. “The aid organisations help people with food, but not as much with, say, water collection systems that could help the farmers survive these droughts.”

For Hervé Bund, Honduras country director for Trōcaire, an Irish aid organisation helping to develop organic farming practices and providing emergency food supplements to rural families, it’s important to “work with the municipal governments so that their plans for local developments have a focus on adaptation to climate change”.

But a day after the publication of the latest World Disasters Report 2020, Matthew Cochrane, a spokesperson for the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), told a UN press conference in Geneva that although Honduras was one of the region’s most vulnerable countries to climate change, it received only $1.22 per person in climate adaptation funding in 2018 – around half the rate of neighbouring Nicaragua.

For Maite Matheu, Honduras country director for CARE, the biggest challenge is working out “how to help construct resiliency for families engaged in subsistence agriculture who are facing prolonged droughts, for five years, and who are then getting pounded by these (storms).

“It’s such a challenge,” she told TNH. “Because all the hard work that’s done to help strengthen food security is put at risk if we don’t do this.”

For some Hondurans, there’s a sense that – although well-intentioned – the international aid effort needs to look deeper.

“They come to Honduras with an outsider's view; the vision brought in from another place,” Zúñiga Cáceres said of international aid organisations. “They know there [are problems] here, but they very often don’t look for and try to fix what’s behind the problems here in Honduras. They don’t understand the reality and the causes behind those problems.”

Walsh, from Catholic Relief Services, admitted that the “very important” work of the NGO sector was “not sufficient”.

“We can’t do it on our own. We can’t carry out these projects on a scale that would be necessary to help these people,” he said. “In the humanitarian sector, we have to get over the idea that we need to only respond to these droughts. They aren’t just a one-off event. Due to climate change, they’re here to stay. The way to deal with it is [to] mitigate climate change, as well as helping foment better farming practices to live with it.”

jo/pdd/ag