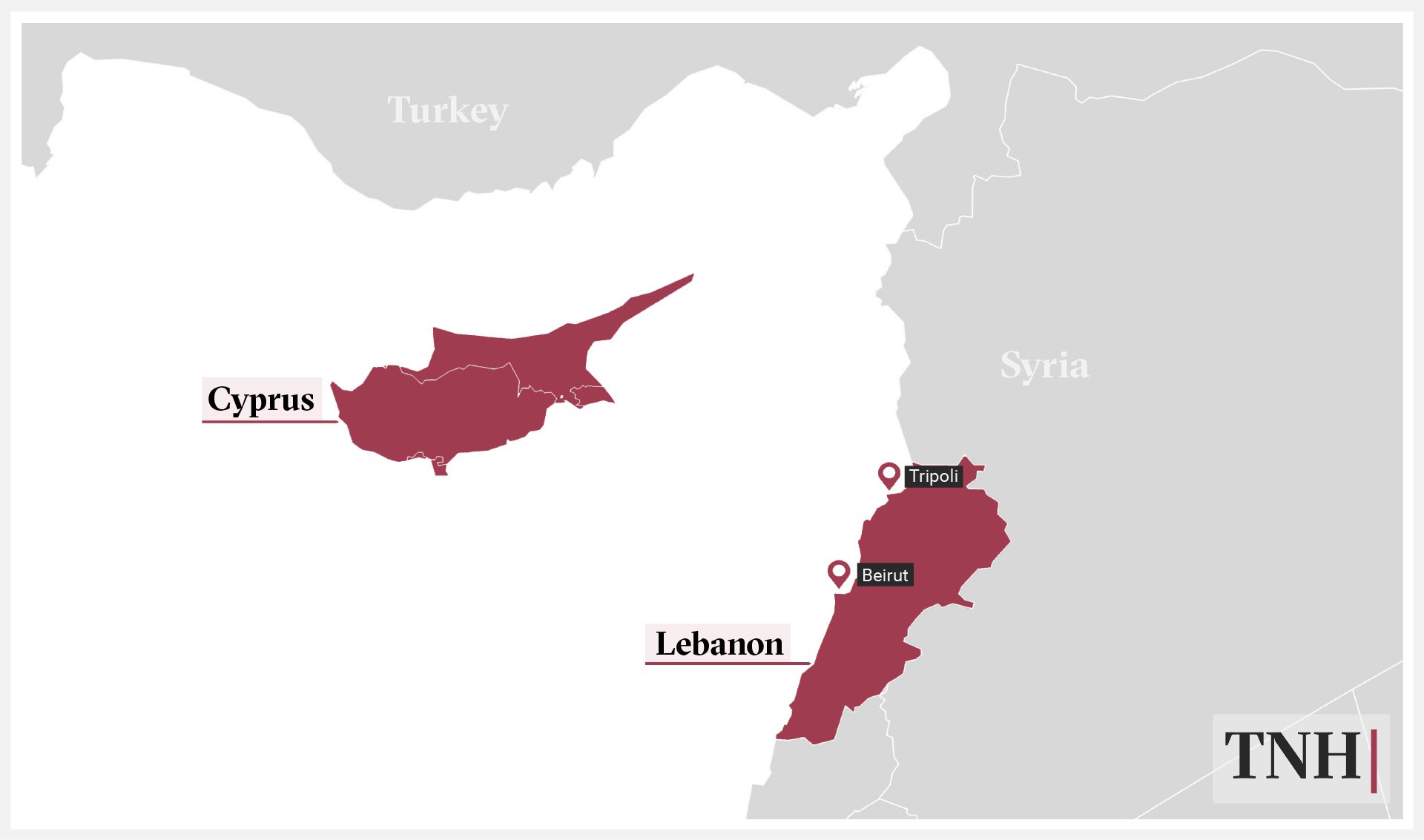

Driven by increasingly desperate economic circumstances and security concerns in the wake of last month’s Beirut port explosion, a growing number of people are boarding smugglers’ boats in Lebanon’s northern city of Tripoli bound for Cyprus, an EU member state around 160 kilometres away by sea.

The uptick was thrown into sharp relief on 14 September when a boat packed with 37 people was found adrift off the coast of Lebanon and rescued by the marine task force of UNIFIL, a UN peacekeeping mission that has operated in the country since 1978. At least six people from the boat died, including two children, and six are missing at sea.

Between the start of July and 14 September, at least 21 boats left Lebanon for Cyprus, according to statistics provided by the UN’s refugee agency, UNHCR. This compares to 17 in the whole of 2019. The majority of this year’s trips have happened since 29 August.

Overall, more than 52,000 asylum seekers and migrants have crossed the Mediterranean so far this year, and compared to Libya, Tunisia, and Turkey – where most of these boat journeys originate – departures from Lebanon are still low. But given the deteriorating situation in the county and the sudden increase in numbers, the attempted crossings represent a significant new trend.

Fishermen at the harbour in the Tripoli suburb of Al Mina told The New Humanitarian that groups of would-be migrants have been leaving in recent weeks on fishing vessels to the small island of Rankin off the coast, under the pretense of going for a day’s swimming outing. They then wait on the island to be picked up and taken onward, normally to Cyprus.

Lebanese politicians have periodically used the threat of a wave of refugees heading for Europe to coax more funds from international donors. Former foreign minister Gebran Bassil told French President Emmanuel Macron after the 4 August port explosion that “those whom we welcome generously, may take the escape route towards you in the event of the disintegration of Lebanon.”

The vast majority of those trying to reach Cyprus – many hope to continue on to Germany or other countries in mainland Europe – have been Syrian refugees, whose situation in Lebanon was precarious long before its descent into full-on financial and political meltdown over the past year.

Syrians are still the largest group, but as the coronavirus pandemic has exacerbated the multiple crises facing Lebanon – the country recorded a record 1,006 COVID-19 cases on 20 September, precipitating calls for a new lockdown – Lebanese residents of Tripoli told The New Humanitarian that an increasing number of Lebanese citizens are attempting, or considering, the sea route.

“How many people are thinking about it? All of us, without exception,” Mohammed al-Jindi, a 32-year-old father of two who manages a mobile phone shop in Tripoli, said of people he knows in the city.

The Lebanese lira, officially pegged to the dollar at a rate of about 1,500, has lost 80 percent of its value over the past year. Prices of many basic goods have skyrocketed, and more than half of the population is now estimated to be living in poverty. The port explosion – which destroyed some 15,000 metric tonnes of wheat and displaced as many as 300,000 families, at least temporarily – has compounded fears about worsening poverty and food insecurity.

Adding to the uncertainty, it has been nearly a year since the outbreak of a protest movement calling for the ouster of Lebanon’s long-ruling political class, blamed for much of the country’s dysfunction, including the port explosion. The economic and political turbulence has led to fears about insecurity, wielded as a threat by some political parties. These fears were underscored by violent clashes in Beirut’s suburbs that left two dead at the end of August.

“In desperate situations, whether in search of safety, protection, or basic survival, people will move, whatever the danger,” Mireille Girard, UNHCR representative in Lebanon, said in a statement following the 14 September incident. “Addressing the reasons of these desperate journeys and the swift collective rescue of people distressed at sea are key.”

‘It’s the only choice’

Al-Jindi is planning to take the sea route himself and bring his family later. But so far he has been unable to scrape together the approximately $1,000 required by smugglers – the ones he has contacted insist on being paid in scarce US dollars, not Lebanese lira. The currency crisis means al-Jindi’s monthly salary of 900,000 Lebanese lira, previously worth $600, is now worth only around $120.

The port explosion in Beirut added insecurity to al-Jindi’s list of worries. He lives in the neighbourhood of Bab al Tabbaneh – which has sporadically clashed for years with the adjacent neighborhood of Jabal Mohsen – and fears a return of the conflict.

“I don’t want to let my children live the same experiences… the sound of explosions, the sound of shooting,” al-Jindi said. After the port explosion, he added, “1,000 percent, now I have a greater desire to leave.”

Paying for a smuggler’s services is beyond the reach of many Lebanese. But members of the country’s shrinking middle class, frustrated with a lack of opportunities, are also contemplating the Mediterranean journey.

“I don’t want to let my children live the same experiences… the sound of explosions, the sound of shooting.”

Educated young people are more likely to apply for emigration through legal routes.

According to Lebanese research firm Information International, about 66,800 Lebanese emigrated in 2019, an increase from the previous year. The firm also reported a 36 percent increase in departures from the Beirut airport after the explosion.

But with COVID-19 travel restrictions and the general trend of tightening borders around the world, some Lebanese are also turning to the sea.

Unable to find steady work since he graduated from university with a degree in IT two years ago, 22-year-old Mohammed Ahmad had applied for a visa to Canada, without success, before deciding to take his chances on the sea route. Before the port explosion, Ahmad had already struck a deal with a purported smuggler to take him to Cyprus and then Greece for 10 million Lebanese lira (the equivalent of around $1,200 at the black exchange market rate). The explosion has only strengthened his resolve.

“Before, you could think, ‘Maybe the dollar will go down, maybe the situation will get better,’” said Ahmad. “Now, you can’t think that way. We know how the situation is.”

Mustapha Masri, 21, a fourth-year accounting student at Lebanese University, said he hadn’t planned on leaving Lebanon, “but year after year the situation got worse.” Like Ahmad, Masri first tried emigrating legally, but without success.

A few months ago, acquaintances referred him to a smuggler. He began selling his belongings to raise the funds for the trip, beginning with his laptop, which he traded for a cheaper one. Even his parents were willing to sell valuables to help him, Masri said.

“In the beginning, they were against it, but after Australia and Germany denied me, they agreed,” Masri said. “It’s the only choice.”

Increasing movement

The past two months have shown a significant uptick in crossings.

According to UNHCR statistics, in all of 2019, only eight boats from Lebanon arrived in Cyprus, seven were intercepted by Lebanese authorities before getting to the open sea, and two went missing at sea.

In 2020, three boats are known to have left Lebanon for Cyprus in July, followed by 16 in the weeks between 29 August and 9 September, said UNHCR spokeswoman Lisa Abou Khaled. Eight of those boats were confirmed to have reached Cyprus and another two were reported to have arrived but could not be verified, she said. Another five were intercepted by Lebanese authorities and four were pushed back by Cypriot authorities before they reached the island and returned to Lebanon.

“From our conversations with the individuals, we understand that the majority tried to leave Lebanon because of their dire socio-economic situation and struggle to survive, and that a couple of families left because of the impact of the blast,” Abou Khaled said.

The pushbacks by Cypriot authorities have raised concerns among refugee rights advocates, who allege that Cyprus is violating the principle of non-refoulement, which states that refugees and asylum seekers should not be forcibly returned to a country where they might face persecution.

Loizos Michael, spokesman for the Cypriot Ministry of Interior, said of the arriving migrants: “At this point we can only confirm the increase in boats arriving in Cyprus…The Cypriot government is in close cooperation with the Lebanese authorities and within this framework are trying to respond to the issue.”

In 2002, Lebanon and Cyprus signed a bilateral agreement to cooperate in combating organised crime, including illegal immigration and human trafficking.

Peter Stano, a spokesman for the European Union, said that the EU Commission takes allegations of pushbacks “very seriously”, adding, “It is essential… that fundamental rights, and EU law more broadly, is fully respected.”

Worth the risk?

The sea route to Cyprus is often deadly, as the 14 September incident underscored. To increase their earnings, smugglers pack small vessels beyond their capacity. More than 70 people have died or gone missing in 2020 on the Eastern Mediterranean sea route – which includes boats bound for Cyprus and Greece – up from 59 all of last year.

Those who TNH spoke to who were contemplating the crossing said they were aware of the dangers but they still considered it worth the risk to attempt the journey.

“I don’t believe all the talk that life there is like paradise.”

“There are a lot of people who have gone and arrived, so I don’t want to think from the perspective that I might not arrive,” said Ahmad, the 22-year-old IT graduate. He was sanguine too about what he might find if he makes it to Europe. “I don’t believe all the talk that life there is like paradise and so on, but I’ll go and see,” he said.

But the plans of both Ahmad and Masri hit a glitch.

The two young men – who do not know each other – had been expecting to travel last month. Both had paid a percentage of the agreed-upon fee to the purported smuggler as a deposit, the equivalent of about $100. In both cases, soon after they paid, the smuggler disappeared. When they tried contacting him, they found his line had been disconnected.

Still, they haven’t given up.

“If I found someone else, I would go – 100 percent,” Masri said. “Anything is better than here.”

ase/er/ag