Beginning on 1 August 2018 and continuing for almost two years, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo grappled with the world’s first Ebola outbreak in an active conflict zone. It became the country’s deadliest outbreak to date and, with more than 2,200 lives lost, the second deadliest anywhere so far.

On 25 June it was officially declared over, though responders are mindful that more than 1,000 survivors could relapse or infect others through body fluids, and that further outbreaks are likely in other parts of Congo, where Ebola remains endemic.

The New Humanitarian was on the ground reporting throughout the just-ended epidemic. On this page, we’ve gathered all our key coverage so you can look back, explore what took place, and ponder the lessons learnt. We will continue to report on the aftermath of the epidemic and on new outbreaks, including cases detected in the northwest of the country in June.

Many had hoped that medical advances, including new vaccines and drug therapies, would help DRC avoid a major epidemic of the kind that ripped through West Africa from 2014-16, costing 11,300 lives, mainly in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone.

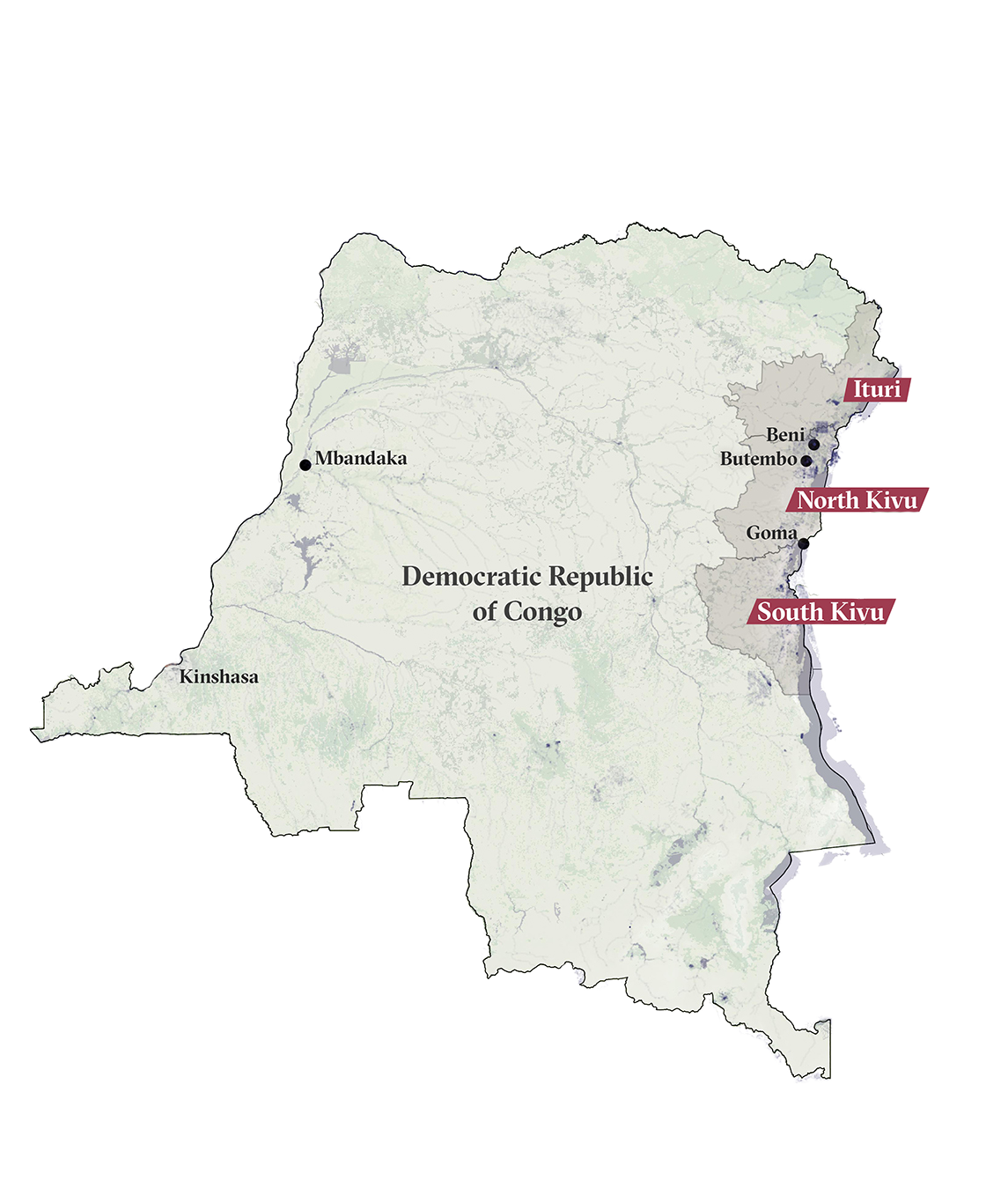

But the 2018-2020 outbreak – concentrated in the provinces of North Kivu and Ituri – proved unlike anything that had come before, taking place in an area where dozens of armed groups have wreaked havoc for decades.

There, the basic work of epidemic control – treating patients, tracing and vaccinating their contacts, and safely burying the dead – was undermined by violent clashes, hundreds of attacks on Ebola responders and treatment centres, and mistrust of health workers.

Mistakes made by responders contributed to the problems. Community engagement was insufficient at the start of relief efforts and residents wondered why the illness seemed to be the only one of interest to the international community, when conflict and other curable diseases were costing many more lives.

Soldiers and police officers – long distrusted in the region – were seen stationed outside treatment centres and escorting responders around towns and villages, further heightening tensions.

And, in a country Transparency International ranks as among the world’s most corrupt, questionable practices in the response – including payments to security forces, renting vehicles at inflated prices, and job kickback schemes – created fertile ground for what residents dubbed “Ebola business”.