No country escapes coronavirus unscathed, but South Africa seems to have done better than most – despite dire predictions that African countries are a “ticking time bomb” of COVID-19 devastation.

President Cyril Ramaphosa has won international praise for a generally sure-footed response, and, after years of bad news, the country is experiencing a tentative feel-good bloom over its ability to pull together.

South Africa has recorded some 26,000 positive coronavirus cases, with over 550 deaths. On 1 June, the government will ease what have been fierce lockdown measures, despite some criticism this is premature. It has warned it will not hesitate to reimpose stringent conditions should there be an uptick in cases.

This briefing looks at some of the positives that have emerged from South Africa’s coronavirus experience, and the potential for longer-lasting changes as the government uses the crisis to drive controversial economic and social reforms.

Less gang violence

South Africa’s notoriously violent gangs called a national ceasefire in April after the first few weeks of the lockdown. “The Council”, said to represent gang leaders from across the country’s nine provinces, declared the truce to allow gang members to help their families through the pandemic.

Gang violence has been a scourge – responsible for more than 4,000 murders in Western Cape province alone from 2019 through to March 2020. But in the first week of the lockdown, the overall homicide rate fell by more than 70 percent, down from 326 killings to 94, compared to the same period last year.

Read more → Coronavirus vaccine trials in South Africa no ‘magic bullet’ as cases soar

The lockdown has also affected the narcotics supply chain – the business that drives much of the gang violence – and drug demand has reportedly fallen (although in some cases it has been replaced by bootleg alcohol).

Brian Williams, a Cape Town-based expert on peace, mediation, and reconciliation, told The New Humanitarian that the truce has been a reprieve for gang-afflicted communities, but he added that the gang structures had remained “intact” during the security clampdown and that for “peace to be meaningful, it must also be sustainable”.

Reduced booze-fuelled deaths

Among the government’s lockdown measures was a booze ban. South Africa has the highest alcohol consumption in Africa per capita, nearly double the continent’s average.

Alcohol’s debilitating impact on society was starkly exposed by its sudden and unexpected prohibition: one of Cape Town’s main trauma units, at Groote Schuur Hospital, reported a two-thirds drop in trauma cases after the lockdown and alcohol ban came into force.

The four-day Easter weekend registered an 81 percent fall in road accident fatalities compared with last year, down from 162 deaths to 28. Overall, 62,300 deaths annually – the majority among low-income earners – can be attributed to alcohol.

Aadielah Maker Diedericks, regional coordinator for the Southern Africa Alcohol Policy Alliance – an eight-country regional NGO network – told TNH that alcohol’s prohibition has allowed for reflection on its “negative impact” and “is giving impetus for the government to regulate and enforce” World Health Organisation recommendations.

Stronger safety nets

The government implemented an early lockdown strategy and then, as the economic pain grew, delivered a $26 billion welfare and business support package equivalent to 10 percent of GDP.

The relief package is projected to increase in the next 18 months to roughly $46 billion.

But that only tempers the humanitarian cost of the stay-home measures, with reports of rising urban malnutrition rates in a country that was already suffering a near 30 percent official unemployment rate before the crisis.

In May, the government’s child grant scheme was almost doubled to $40 a month per child as part of the support package. From June to October, a separate and additional $28 will be paid each month to care-givers as a further cushioning.

The relief package is projected to increase in the next 18 months to roughly $46 billion.

About six million people are also eligible for a $19 monthly temporary unemployment benefit.

Better social services

The hygiene needs laid bare by the virus have prompted a re-examination of water services for the country’s poor.

The statistics agency Stats SA claims that 87 percent of the population has access to “safely managed drinking water service”. But that’s disputed by researchers who point out that “communities in townships, informal settlements and the homeless especially, have trouble accessing water and sanitation resources”.

COVID-19 is therefore prompting calls for the swift enactment of existing government bills on water and sanitation, as well as plans for infrastructure and water quality development.

Coronavirus is also providing ammunition for those demanding a well-resourced public health system.

Before the crisis, a National Health Insurance Bill aimed at universal health coverage financed by single payer contributions faced resistance from the private medical sector, opposition parties, and some taxpayers.

That pushback is waning in the face of an emerging consensus that a robust health system is an essential tool in managing the coronavirus pandemic and future public health crises.

Economic reform

Ramaphosa described the pandemic as the watershed moment for the transition from the legacy of apartheid to a more equitable economic model. Earlier this month, he cast it as a “post-war situation”.

The uneven economic devastation wrought by the pandemic – targeting low-income earners from the tourism and service industry, through to the mining, manufacturing, and transport sectors – has underlined those arguments that South Africa needs a new development path.

Public Enterprises Minister Pravin Gordhan has been given a freer hand to dispose of ailing and allegedly corruptly run state-owned assets, such as the loss-making flag carrier South African Airways (SAA), and overhaul the heavily indebted state energy provider Eskom.

The depth of the economic crisis is also blunting objections from sections within the ruling ANC – and its trade union and Communist Party allies – over the way the government intends to finance its recovery plan. It is sourcing funding from the traditionally fiscally conservative International Monetary Fund and World Bank – institutions seen as opposed to public sector-driven growth and affordable social services.

A Special Investigating Unit, an independent statutory body accountable to parliament and the presidency, is vowing to pursue any corruption linked to the bailout. Civil society is also sparring against lockdown regulations and court challenges to keep a check on any constitutional overreach.

Lemons to lemonade

There is a marked contrast between the government’s speedy response to COVID-19 and the HIV denialism of the administration of Thabo Mbeki two decades earlier.

The effective coronavirus action – despite reports of policy squabbles among the government’s scientist-heavy advisory body – has generated significant goodwill among healthcare professionals and civil society activists.

“The kind of camaraderie and willingness to solve this is unprecedented,” Glenda Gray, who is head of the South African Medical Research Council and a member of the Ministerial Advisory Committee, told TNH.

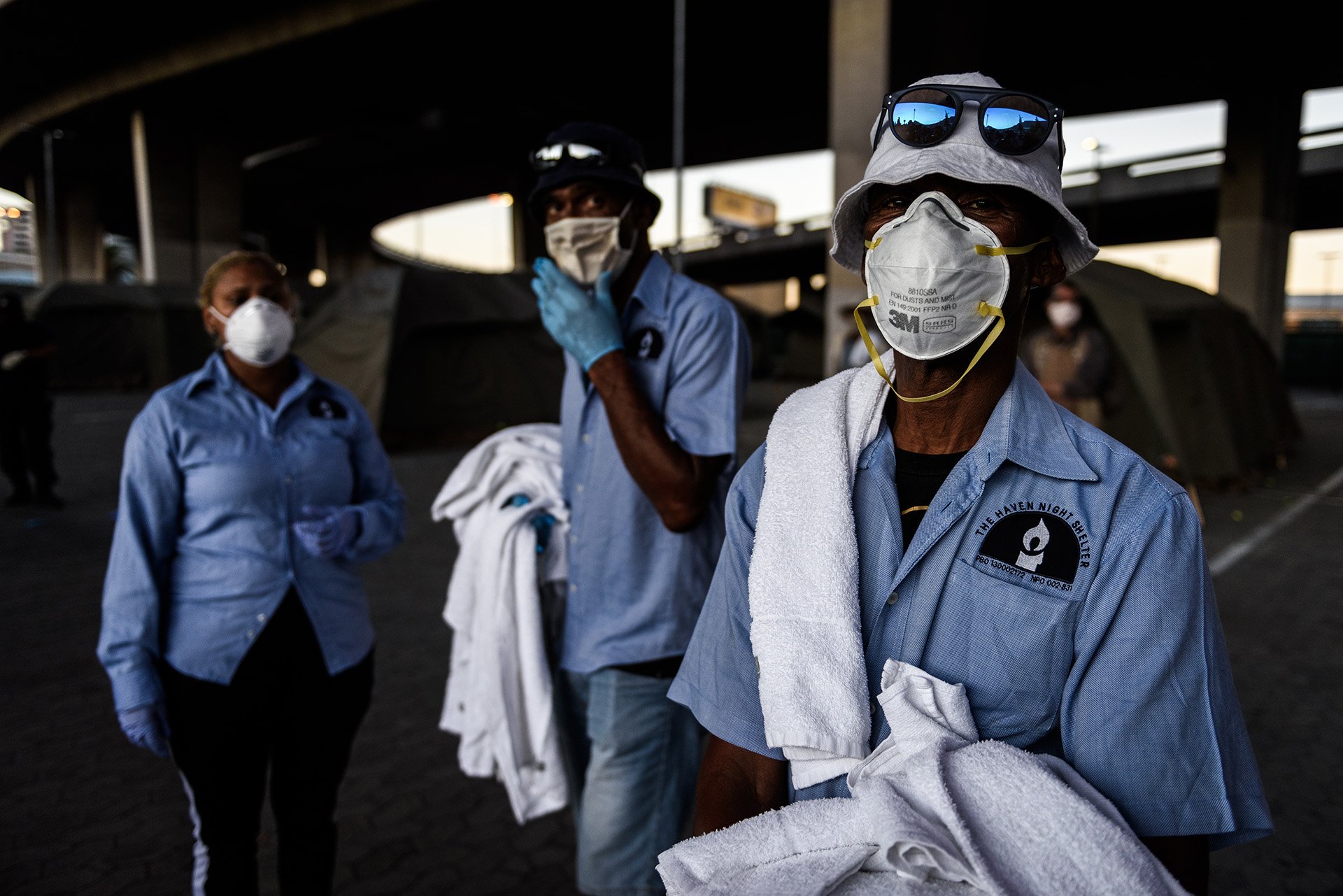

South Africa has capitalised on a health system and network of community workers built to combat HIV and other infectious diseases. Thousands of health workers have been deployed on nationwide door-to-door screening operations, and more than 635,000 tests have been conducted – far better than most wealthier countries have managed.

South Africa, Africa’s second largest economy, has a sophisticated medical research infrastructure that is coming into its own with COVID-19. Collaboration is being fast-tracked – with particular attention going to the data around the epidemiology of the virus in an African setting – and money is being steered towards coronavirus work.

Public and private technology resources are being corralled by the government, including a map project that aggregates public information to determine the health vulnerabilities of specific communities. Innovation also includes a self-sanitising coating that can reduce surface contamination, developed by a University of Witwatersrand PhD student.

Local philanthropy has also pitched in to help with the impact of the lockdown on the poor. The private sector-driven Solidarity Fund has received pledges of $108 million to date, and local relief organisations, from the Gift of the Givers through to the Angel Network, are part of a diverse civil society network in South Africa that is working to combat hunger.

go/oa/ag