Indigenous leaders are warning that a combination of neglect, inadequate preparations, and a lack of lockdown measures is exposing remote and vulnerable communities in the Amazon to potentially devastating outbreaks of COVID-19.

The nationwide death toll in Brazil has soared above 11,000 amid growing anger at President Jair Bolsonaro’s dismissive response. The situation is particularly bad in the Amazon gateway city of Manaus, where the number of fatalities is feared to be many times the official 500-600.

Peru and Ecuador also have large outbreaks and significant Amazonian indigenous populations. In Ecuador, which has the highest COVID-19 death rate per capita in Latin America – more than twice that of Brazil – dozens of elders and children from the Siekopa’ai (Secoya) community, which has been decimated by disease in the past, fled by canoe to isolate themselves in the central wetlands of Lagarto Cocha. By 5 May, there were already 15 confirmed cases and two suspected deaths among its population of 744.

“No specific attention has been given to indigenous communities,” Gregorio Díaz Mirabal, chief coordinator of the Indigenous Organisations of the Amazon Basin, or COICA, an association of South American indigenous groups, told The New Humanitarian. “The pandemic has exposed that there are no doctors and no health infrastructure in these communities. There is no education, no phone connections, no computers, no internet.”

According to the 2010 census, some 817,000 Brazilians identify as indigenous, occupying 12.6 percent of the national territory. Mining, oil extraction, and deforestation have encroached onto their lands and threatened their way of life.

Despite the fact the region is still recovering from catastrophic 2019 wildfires, Bolsonaro announced in April that a vast Amazon reserve could be opened for mining. Emboldened by the president's stance, deforestation increased 51 percent during the first quarter of this year.

Amazonas is the Brazilian state with the largest indigenous population: more than 180,000. The largest individual community in Brazil is the Guarani, numbering 51,000, but the Yanomami, with 19,000 members, occupy the largest territory, some 9.4 million hectares.

The first indigenous death in Brazil was reported on 9 April when a 15-year-old member of the Yanomami succumbed to COVID-19 in the state of Roraima, an area long targeted by illegal gold miners. Since then, dozens more indigenous fatalities have been reported.

Reliable data on indigenous infections and deaths from COVID-19 is hard to come by. As of 11 May, APIB, the largest umbrella group of indigenous organisations in Brazil, said 68 indigenous people had died across the country, with 283 infected.

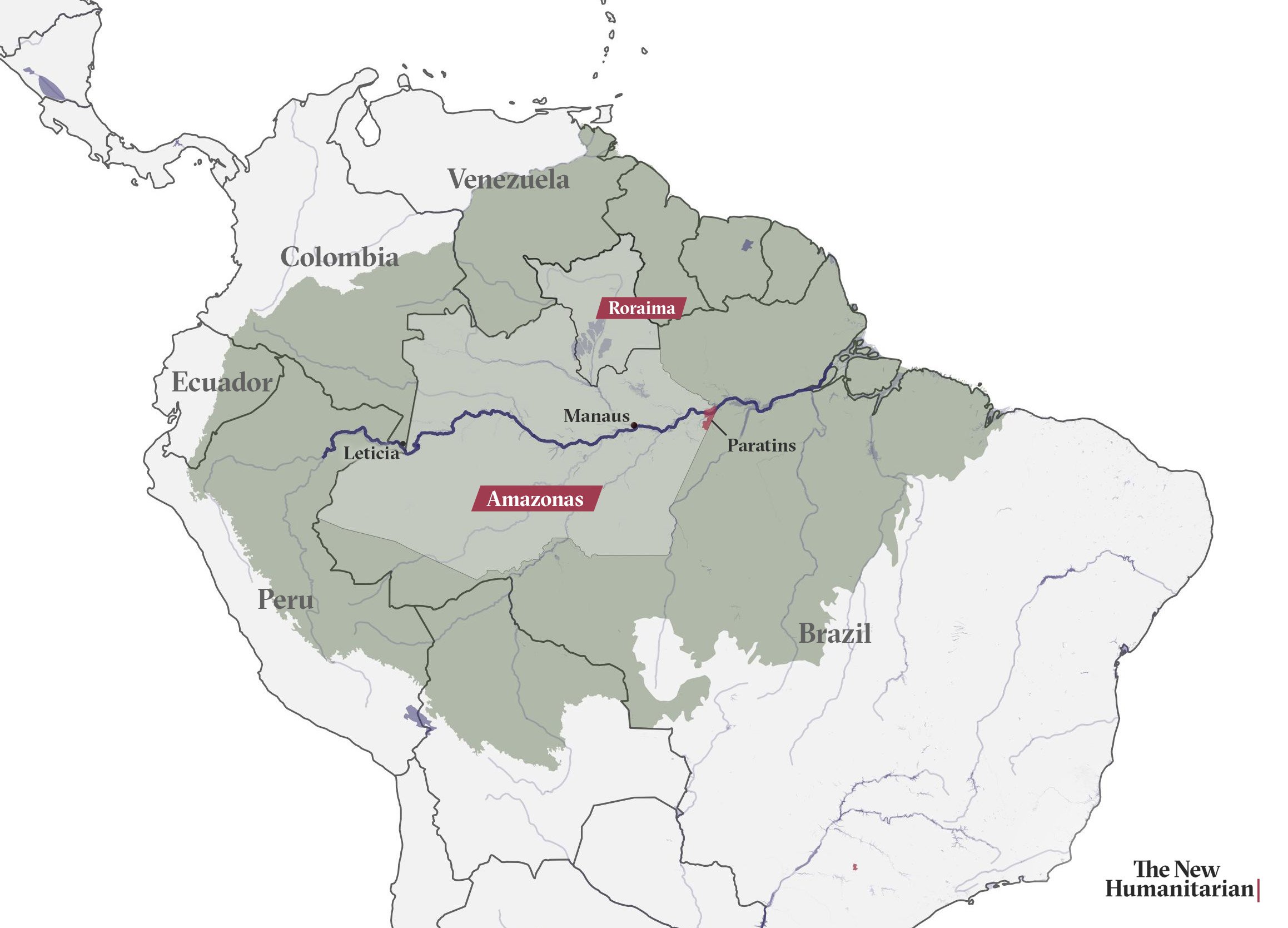

As of 8 May, the Pan-Amazonian Ecclesiastical Network had recorded 36,602 confirmed COVID-19 cases and 2,247 deaths across the Amazon region, which encompasses much of northwestern Brazil and extends into Colombia, Peru, and several other South American countries. However, this data includes both indigenous and non-indigenous people.

The Amazon region

No controls on the river

Whatever the real figures, the number of COVID-19 cases is rising, and with each daily rise the frustration of indigenous leaders builds at what they see as a lack of planning and consultation on measures to protect their communities from the spread of the virus.

“No specific protocol exists,” said Díaz Mirabal. “No direct care and support to us exists, and there is no coordination of policies with us.” In the nine countries where COICA works, only nine hospitals serve some three million indigenous people, he added.

Tito Menezes, a member of the Sateré-Mawé and the group’s first lawyer, explained how the Brazilian government refused to shut down economic activity and allowed traffic to continue up and down the Amazon River despite the obvious dangers for indigenous communities.

Most of the more than 15,000 Sateré-Mawé live in approximately 50 villages spread over nearly 8,000 square kilometres known as the Andirá-Marau Indigenous Land, at least five hours by boat from the nearest town of Paratins.

Menezes said local state authorities ended up setting up checkpoints along two tributaries that access the indigenous land after a respected chief, or Tuxaua, Otávio dos Santos, died on 17 April from COVID-19. The chief’s family said his condition was not taken seriously enough to begin with, and he was tested too late.

“The people were worried, as outsiders continued coming and going,” Menezes told TNH from Paratins, where 1,000 members of his community live, eight hours downriver by boat from Manaus. “There is no security,” he added.

Leticia, a city on the banks of the Amazon – bordering both Brazil and Peru – is now recording Colombia’s highest rate of COVID-19 infections, raising concerns that South America's biggest waterway may be responsible for significant spread of the virus.

There are more than 800 different indigenous groups in Latin America – 2014 estimates put their overall population at more than 40 million. In many countries, they have little political representation and lag behind non-indigenous compatriots in terms of health outcomes.

Outside the Amazon region, Chile and Mexico also have large COVID-19 outbreaks and significant indigenous populations, while there are growing concerns over the outbreak in Guatemala, where more than four in 10 people classify as indigenous.

At particular risk, but neglected

Amazonian indigenous groups are especially vulnerable to dying if they contract COVID-19 because they often live days away from professional medical help. Even if they do find transport and reach a hospital, in Manaus it is likely to be overcrowded and under-resourced.

Vulnerability to certain diseases, including COVID-19, may be heightened due to precarious living conditions.

“Indigenous communities historically have been prone to living in extreme poverty,” explained Marcos Espinal, director of communicable diseases at the Pan American Health Organisation (PAHO). “They are also prone to have... malnutrition and pre-existing conditions. Other issues are access to supplies, food security, to water and sanitation.”

“Indigenous groups need to be prioritised,” he added.

Earlier epidemics in the world’s largest rainforest have decimated indigenous populations.

“Indigenous groups need to be prioritised.”

Between 1987 and 1990, 14 percent of Yanomami were killed by measles, brought to their communities by miners. And almost one in four Yanomami in four villages died in earlier illnesses after becoming infected when public works took place nearby.

APIB recently accused authorities in Amazonas of “institutional racism” and condemned the “lack of medical attention” for indigenous people in the state. “In the context of indigenous peoples, the government hasn't mentioned the slightest concern about the situation,” a spokesperson said. “The invisibility is total.”

The Dos Santos family said they had not received the chief's death certificate nor been told where he was buried. “We are not a priority for care from SESAI,” the chief’s son wrote in a letter to Menezes, referring to the government’s indigenous health service and accusing it of failing to provide an adequate response after COVID-19 reached their community.

Anger at the government over the coronavirus comes amid fears that Bolsonaro plans a new push to spread Christianity among indigenous communities – a move a UN special rapporteur described recently as having the potential to cause “genocide”.

The president, who regularly makes racist remarks, fuelled these concerns in February by appointing an evangelical pastor and former missionary to head the department for isolated and recently contacted tribes at the government’s indigenous agency, FUNAI.

Lax government response

Menezes said critical information about the coronavirus was not reaching people in the Andirá-Marau Indigenous Land.

“Few communities have access to Facebook, Twitter, or messages in newspapers on the pandemic,” he told TNH. “How can they protect themselves properly without the information?”

The situation is particularly worrying due to its relative proximity to Manaus, where the mayor recently issued a tearful call to world leaders for help. Images of body bags scattered amongst ailing patients in overwhelmed healthcare centres have circulated on social media.

While Brazil’s national response was undermined by Bolsonaro’s suggestion that the disease was nothing more than a “little flu”, indigenous groups in the Amazon have been urging their communities to self-isolate, and to be wary of infection from outsiders, including medical staff.

“Few communities have access to Facebook, Twitter, or messages in newspapers on the pandemic. How can they protect themselves properly without the information?”

APIB reported that a SESAI doctor was responsible for spreading the disease in March amongst the Kokoma, an indigenous community in the Amazonas region of Alto Solimões, where 61 indigenous people tested positive last week (4 May), according to APIB.

COICA’s Díaz Mirabal, himself a member of the Wakuenai Kurripaco community in Venezuela, pointed out the lack of assistance for indigenous communities across Latin America, where he said no COVID-19 aid packets, food, or vouchers are being distributed.

In Brazil, emergency government payments of 600 real ($115) to help those in need can only be accessed by signing up. For many indigenous people this means travelling hours on a crowded boat to the nearest town. Some 23 million Brazilians, including 41,000 indigenous people, have reportedly signed up for the payments, due to be disbursed each month for three months.

In Peru – which has the second highest number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in the region after Brazil – AIDESEP, the largest association of indigenous communities, has denounced the lack of government action and referred to the “risk of ethnocide in Amazon indigenous communities”.

Oxfam’s Miguel Levano said the Peruvian government needed to consult with the indigenous peoples and implement emergency plans, but he recognised there were thorny problems to overcome. “What is difficult for the government to understand is that entry into the communities must be avoided without protective equipment, [but also that tests must] be carried out,” Levano said.

Little humanitarian aid

PAHO, the regional branch of the World Health Organisation, has recommended that governments take “targeted and adapted actions” for “populations in situations of vulnerability” to enable access to COVID-19 health services and to facilitate communication in local languages about the pandemic and ensure sanitary measures are taken.

TNH repeatedly asked PAHO and the WHO if a response plan aimed at bringing assistance specifically to indigenous communities facing COVID-19 outbreaks had been drawn up. No spokesperson had answered by time of publication.

On 4 May, the Amazon region’s largest indigenous groups, including APIB and COICA – together with indigenous parliamentarians, environmental NGOs, and celebrities – called on the UN to set up an emergency fund to protect communities from the pandemic.

The written appeal asked WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus to provide protective equipment to medics in villages and reservations.

“Communities have organised efforts to isolate their territories,” it said. “Without the necessary personal protective equipment, this effort puts them at even greater risk. Aid packages promised by the governments are not reaching communities.”

Christian Lindmeier, a WHO spokesperson, said he wasn’t aware of the appeal, but added: “It is true that this is a very vulnerable population. We know that any disease brought into indigenous, isolated populations is a huge challenge for them and needs to be handled very carefully.”

Very few humanitarian organisations, aside from some Church groups, work regularly with indigenous groups in the Amazon. Most international NGOs operating in the region are focused on environmental or human rights issues.

On 5 May, COICA announced the launch of the Amazon Emergency Fund to raise a total of $8 million over 60 days, to buy food, medicine, and protective equipment, and to promote science-based information for indigenous communities.

The COICA initiative is sponsored by Rainforest Foundation US, an environmental NGO that supports the protection of the jungles in Latin America.

“It is a tough time for us to pivot [from environmental to humanitarian work] right now to try to do this,” Suzanne Pelletier, the foundation’s executive director, told TNH, adding that she was “not very” comfortable taking on a role in this area of assistance.

Helping communities in the midst of the pandemic is, however, “the biggest issue facing the indigenous communities, and the Amazon, right now”, Pelletier said. “The indigenous people are the guardians of the forest.”

pdd/ag

Subscribe to our coronavirus newsletter to stay up to date with our coverage