Ten-year-old Soe Min Aung can’t remember the last time he spoke with one of his Muslim neighbours: a bamboo fence has cleaved his community in half, separating his Rakhine Buddhist family from the Rohingya on the other side.

Stakes of wood have been pounded into the middle of the dusty path that once joined the Rakhine and Rohingya sides of Pam Mraung, a village of 500 people located four hours north of the Rakhine State capital, Sittwe.

The Rakhine villagers erected the fence six years ago, when a wave of race-fuelled riots swept over parts of the state and spilled into other areas of Myanmar. Buddhists and Muslims attacked each other, fed by rumours and hate speech that tapped into generations of distrust.

"It's better we don't live together with the Kalar," said Maung Win, a Rakhine farmer who lives near the fence. He used a derogatory term for Muslims in Myanmar, a diverse but majority-Buddhist country.

While such fences aren’t the norm in mixed villages in Rakhine, communities throughout the state are still deeply divided.

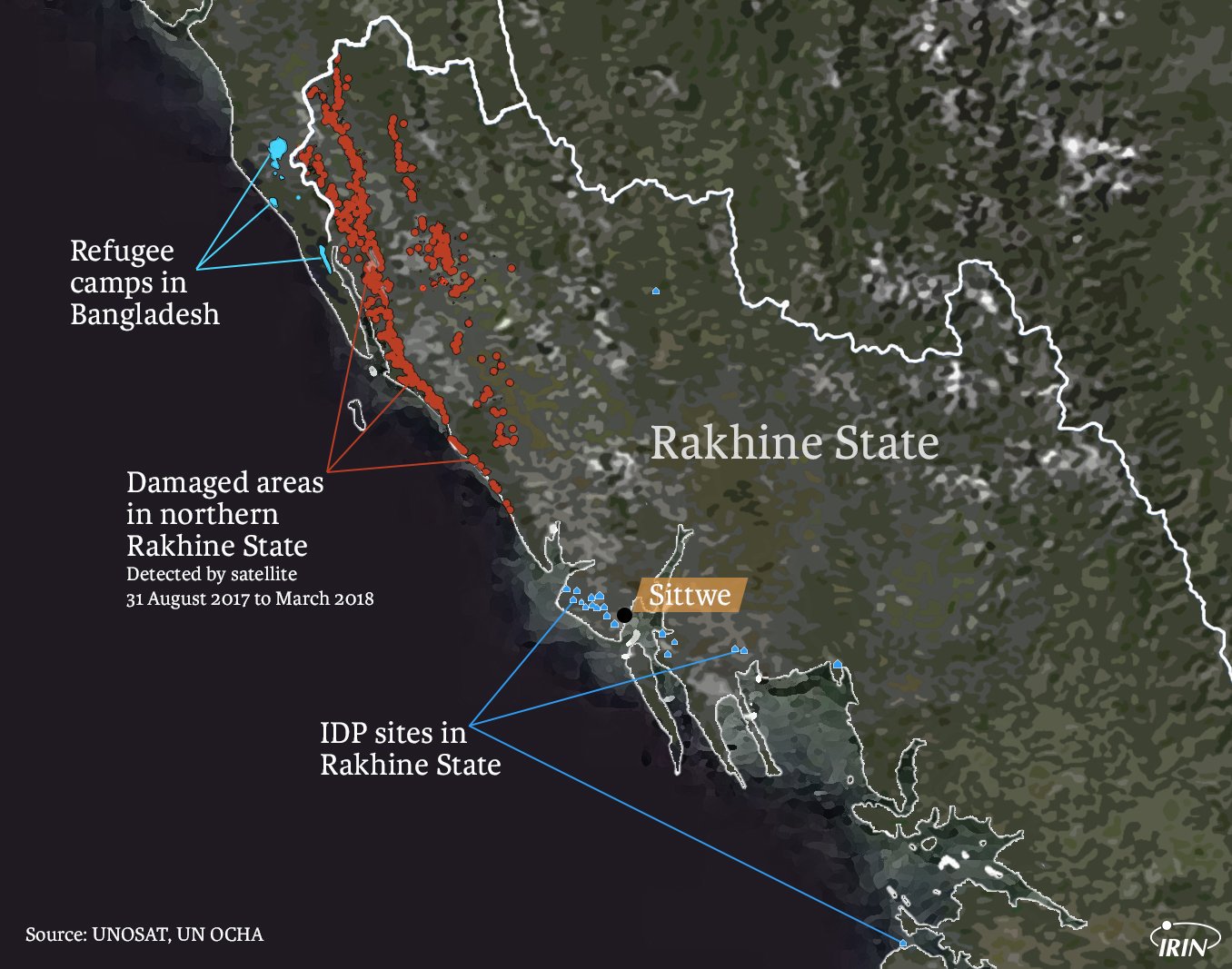

More than 700,000 Rohingya fled a violent military purge in the northern townships last August. Myanmar’s government says its military was responding to border attacks by a small group of Rohingya fighters; a UN investigation says the military response was organised, pre-planned, and likely amounts to genocide.

Communities across the state continue to be split by a gulf of misunderstanding, fear, and apartheid-like policies that isolate the Rohingya from their Rakhine neighbours.

But even in villages like Pam Mraung, important economic ties tether the divided communities together: Rohingya send their children to sell fish to the Rakhine villagers; the Rakhine sell the Rohingya vegetables, or bottles of purified water. Researchers say such links may one day help build trust between the two sides.

But the longer the restrictions remain in place, rights groups warn, the more difficult it will be for the communities to learn to live together again.

“We just don’t want any trouble”

While international media attention centred on last year's Rohingya refugee exodus from the north, the flashpoint for those who live elsewhere in Rakhine was the violence in 2012.

The Rohingya were excluded from Myanmar’s 2014 census, making it hard to know how many of them are left in the country after last year’s exodus, when more than 700,000 Rohingya fled into neighbouring Bangladesh.

The UN has estimated that 470,000 “non-displaced” Rohingya still lived in Rakhine State at the end of 2017. In addition, more than 120,000 internally displaced Rohingya are confined to multiple camps, which are mostly concentrated around the capital, Sittwe.

The government has said it intends to close the camps, which was one of dozens of recommendations made last year in a commission on Rakhine State chaired by former UN secretary-general Kofi Annan.

However, rights groups have said this could entrench the existing segregation if Rohingya are simply moved elsewhere and continue to be denied basic rights such as freedom of movement.

In mid-November, an attempt to begin repatriating Rohingya refugees from Bangladesh to Myanmar failed after the refugees refused to return to Rakhine State.

And some Rohingya are still trying to flee the state. On 16 November, Myanmar authorities said they had arrested 106 Rohingya on a stranded boat near Yangon. The Rohingya had reportedly left displacement camps in Rakhine State to try and reach Malaysia. Police said they later shot and injured four Rohingya men in Ah Nauk Ye, an IDP camp east of Sittwe, after detaining two men alleged to have helped smuggle the group.

After the riots, Rakhine in Pam Mraung pieced together the fence, blocking off the Buddhist and Muslim sides of the village. Today, the wooden posts are joined together by a bamboo lattice, which is replaced a couple of times each year.

Through the holes in the fence, Rakhine villagers can see their Rohingya neighbours, and their Rohingya neighbours can see the Rakhine. But meaningful interaction is limited.

Instead, rumours and distrust fester. The further away from the fence the Rakhine villagers live, the more horrific the stories become. "During the violence in 2012 two women were disembowelled by the Kalar," said one Rakhine woman, lowering her voice. Her home is a five-minute walk from the fence, toward the far end of the Rakhine side.

Maung Win, the farmer, hadn’t heard of the killing the woman described. "I see the Muslims every day and we sleep pretty well here," he said, laughing.

Still, he thinks the two communities are better off apart. He believes the Rohingya are thieves and drunks. “We just don't want any trouble," he explained.

Kept apart

Longtime divisions between Rakhine and Rohingya communities have been reinforced by years of apartheid-like policies that have institutionalised segregation. The Rohingya are denied citizenship in Myanmar and are broadly derided as illegal immigrants from Bangladesh, though they say Rakhine State is their rightful home.

After the 2012 riots, the government forced about 120,000 people, mostly Rohingya, into barren camps, where they remain cut off from their former villages and livelihoods and almost completely dependent on humanitarian groups for survival.

But Rohingya living elsewhere in the state also face strict curfews, heavy restrictions on their movements, and difficulty accessing hospitals and schools. Rights group Amnesty International says that Rohingya children in some areas aren’t allowed to attend classes with Rakhine children; in others, government teachers refuse to teach in Muslim areas. Amnesty says these policies amount to apartheid – a crime against humanity under international humanitarian law.

"The movement restrictions mean a teenager with something as simple to treat as a small, infected wound cannot access care and medicine to heal it,” said Elise Tillet-Dagousset, a human rights researcher who authored the group’s study on apartheid policies in Myanmar.

“It means a father cannot visit his daughter who has been detained for travelling without a permit. It means a five-year-old child would have never met someone who is not from his village or community.”

Along the shoreline of a river near Pam Mraung, Mohammed Saed, a 19-year-old who lives on the Rohingya side of the village, stood shielding his eyes from the late afternoon sun. He had been transporting stones across the river all day long. He is paid to do so by a Rakhine neighbour.

While the monetary exchange keeps him connected to the Rakhine side of the village, much of Saed’s daily life is still defined by animosity and official neglect toward his community. The fence that separates him from his Rakhine neighbours is a lesser problem than the wider restrictions that marginalise the Rohingya.

He doesn’t remember the last time a government teacher came to instruct children on the Rohingya side of his village. If he wants to visit a neighbouring village, he has to pay local authorities a bribe of about 50,000 kyat – roughly $30, or a quarter of his monthly salary. And he’s mindful of the nightly curfews that the Rohingya must adhere to, and of his Rakhine neighbours.

As the sun began to set, Saed grew visibly nervous: “I need to be back in my village before 5pm or there will be trouble.”

Ties that bind

Yet even amid the deeply entrenched segregation, generations-old economic relationships still link the Rohingya and the Rakhine.

"In many cases, economic interactions are the main or only tie left to connect the two communities," said Anthony Ware, a researcher at Deakin University in Melbourne. He has studied social cohesion in Rakhine State since 2011 and is working on a study examining what still ties the Buddhist and Muslim communities together.

Trade between villages and interdependence in agriculture – Rakhine hiring Rohingya to plant rice, for example, or sharing the costs of rice-threshing machines – were the first things that were restored after last year’s violence, he said.

While the economic relationship is rarely equal, with Muslims being far more vulnerable to exploitation than the Rakhine, Ware said such everyday interactions may slowly rebuild trust and overcome tensions.

“If you regularly interact and talk to each other, then minor issues are less likely to become big problems,” he said.

In his work with local researchers, Ware has seen villages where Rohingya and Rakhine re-established social connections through such business ties. He has even seen communities where the two sides had begun to play Chinlone – Myanmar’s popular national sport, played with a rattan ball.

“Given how deep the tensions run, finding villages like this is astonishing,” he said.

There are no inter-communal games of Chinlone in divided Pam Mraung. But back on the Rakhine side of the village, farmer Maung Win wondered what life might be like without the fence. Business might improve, he thought, if he could sell his produce to more customers.

“Maybe it would be better if there was no fence,” he said. “Better for selling my crops.” Then he looked around warily, in case anyone was listening.

For now, the youngest generation on the Rakhine side of Pam Mraung are growing up knowing only segregation and distrust.

“Not afraid. I am not afraid of the Kalar,” said Soe Min Aung, the 10-year-old Rakhine child. The other children around him giggled. He doesn’t remember a time when things were any different.

Do he or his friends ever venture to the other side to play with the Muslim children? He looks puzzled. No, he would never do that, he said. There’s a fence.

(TOP PHOTO: Rakhine and Rohingya neighbours in Pam Mraung village can see each other through holes in the fence. CREDIT: Verena Hölzl/IRIN)

vh/il/ag

The uphill battle to forge peace in Myanmar's Rakhine State

The uphill battle to forge peace in Myanmar's Rakhine State